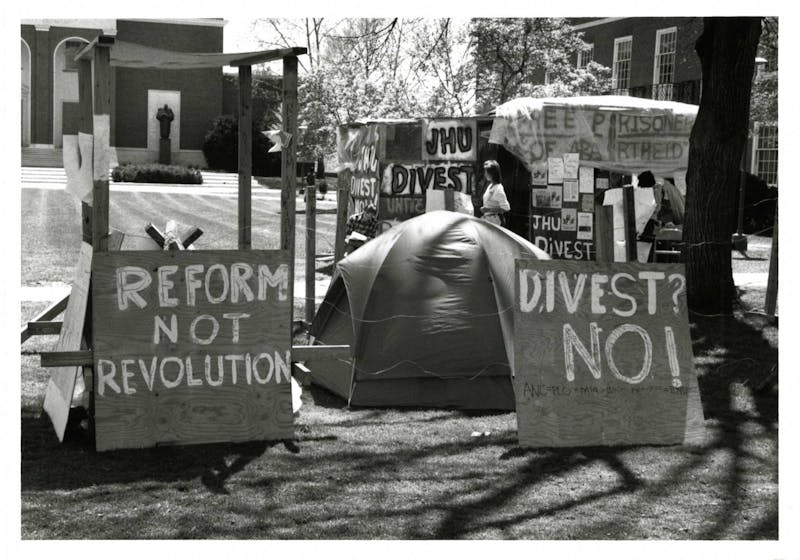

COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SHERIDAN LIBRARIES

Students erected shanties on Wyman Quad in protest against apartheid in South Africa.

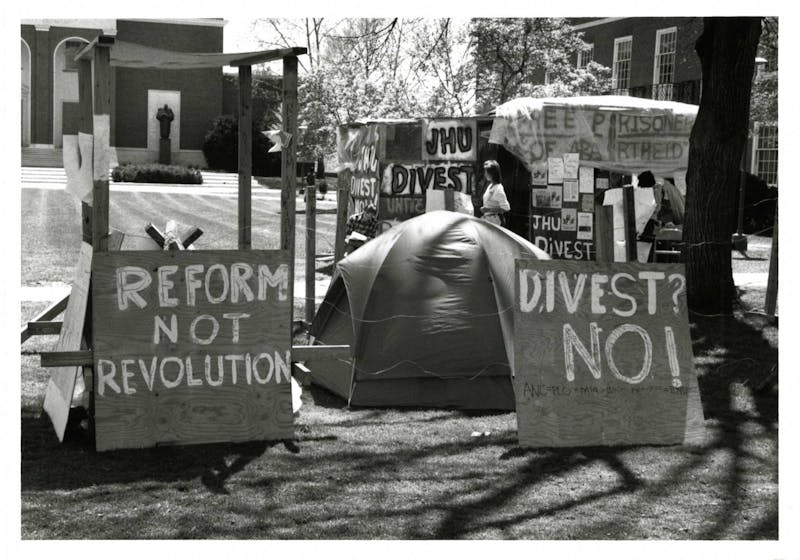

COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SHERIDAN LIBRARIES

Students erected shanties on Wyman Quad in protest against apartheid in South Africa.

In June 1976, roughly 10,000 students in Soweto, South Africa organized a peaceful protest against new legislation decreeing that Afrikaans, alongside English, be used in Soweto high schools. Afrikaans was known as the “language of the oppressor” in apartheid South Africa. Upon their peaceful march toward Orlando Stadium, the protesters were met with heavily armed police. What started off as a tear gas attack eventually turned into firing rounds of live ammunition. Hundreds of people are believed to have died and images of this police brutality spread internationally, sparking a firmer liberation movement by international forces against apartheid.

Beginning in the 1970s, a student-led grassroots movement in the U.S. demanded that universities divest their holdings in South Africa. The campaign’s objective was to damage the South African economy so that the government would acquiesce to the demands of anti-Apartheid protesters nationally and internationally. Universities are often one target of divestment, as many use their endowment funds to invest in business firms.

In 1986, Hopkins students created the Coalition for a Free South Africa. The group’s goal was not only to convince the University to cease investing in South African companies but also to “campaign against banks investment in and loans to South Africa, targeting Maryland National Bank and Citibank.” These movements in the U.S. rose in response to the student protests in South Africa.

As described by the United Press International’s archives, the Coalition at Hopkins gathered at Garland Hall, prepared with anti-Apartheid signs and demands for the administration. These protests, along with a nine-day sit-in, were largely disregarded by the presiding Board of Trustees until the very lives of the students were in danger. There was at least one student report of sexual harassment by police officers and security, and three members of the Delta Upsilon Fraternity firebombed the mock shanty town built by students. Fortunately, none of the protestors were injured, and this incident drew the attention of the press.

In a 1986 article published by United Press International, Coalition spokesperson Patrick Bond stated that faculty began to side with students as well.

“We think the students and faculty would vote overwhelmingly for divestment,” he said.

Indeed, it appeared Bond’s prediction was starting to come true.

In a released note from Oct. 2, 1986, former University President Steven Muller told the board that if “faculty members would join with students... such a circumstance would be non-survivable.“

Following this threat of a faculty-student alliance, the board began a selective, rather than total, divestment resolution less than a month later. In the following years, the University gradually increased divestment until they had successfully divested from all South African companies.

The work of these Hopkins students was one of many nationwide movements that pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. Though President Ronald Reagan initially vetoed the act, Congress overturned that veto and followed by voting for more restrictive sanctions.

Today, South Africa has been freed from the apartheid system, and the Coalition serves as one example of student activism that leveraged change at the university level to lobby for national and international change.