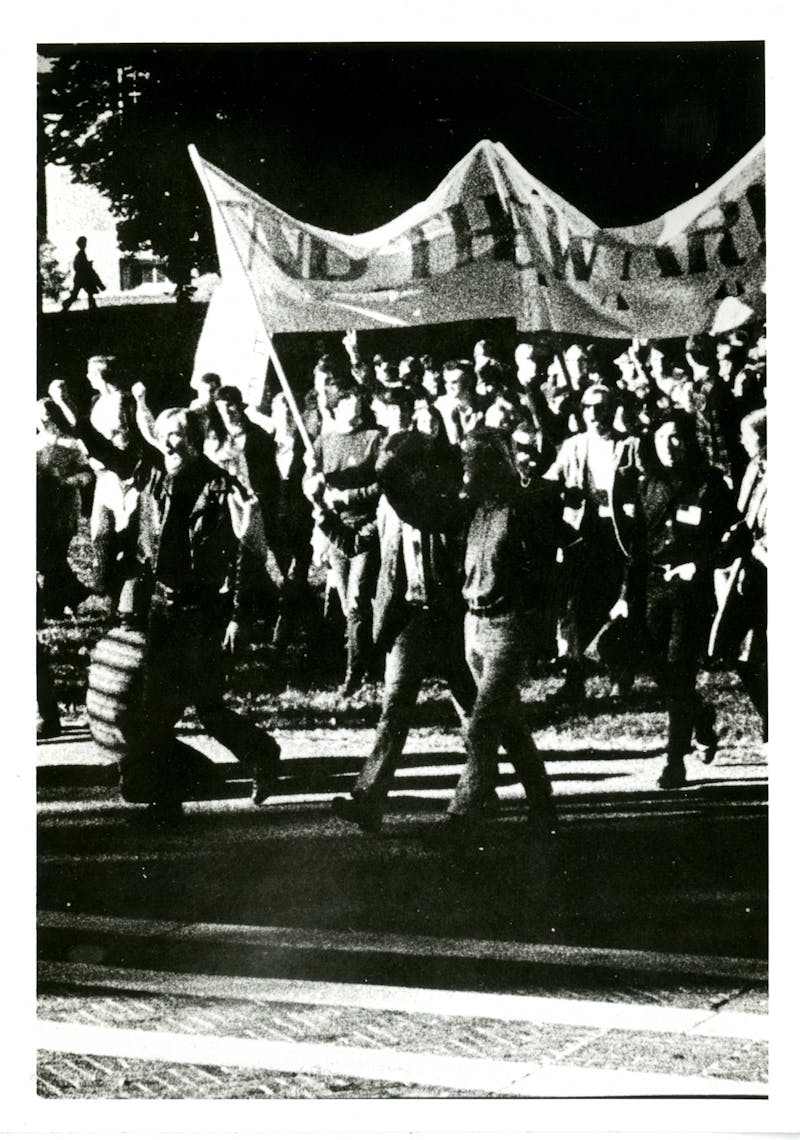

COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SHERIDAN LIBRARIES

Student activism at Hopkins has a long and storied past.

COURTESY OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY SHERIDAN LIBRARIES

Student activism at Hopkins has a long and storied past.

At the very core of society’s progress, activism has always been integral to sparking change. From macroscopic protests advocating for women’s rights to smaller movements concerning local issues, the freedom to assemble is ingrained in the very founding of the United States.

College students especially have always taken advantage of this right. As they transition from childhood to adulthood, undergraduates have a unique understanding of the topics that are affecting both the younger and older generations, and they have the opportunity to make an impact on issues that will still affect them as they grow older.

Though not particularly known as an “activist university,” Hopkins has had its fair share of important milestones in activism throughout the years. In many ways, it has mirrored the trends seen in the histories of peer institutions amid ongoing tensions with the administration and movements on nationwide issues.

Emeritus Professor Stuart Leslie came to Hopkins as a postdoctoral fellow in 1981. He commented on the notion that Hopkins students are not as active compared to students from peer institutions in an interview with The News-Letter.

“It's our smaller size, tradition and our majority STEM students,” he said. “Hopkins doesn’t really have a tradition of activism. There were antiwar protests in the ’30s and protests against or in support of civil rights issues, but they were small protests. STEM students don’t traditionally have as much of a role in protests as humanities students.”

While students may not have seemed as active in recent decades to Leslie, he highlighted that the history of Hopkins has been greatly influenced by movements and protests.

A brief history of student activism

While there have been many examples of youth activism throughout history, the earliest record of student activism at a U.S. university was the “Great Butter Rebellion” of Harvard University in 1766, where students protested the university for serving rancid butter.

Student rebellions sparked across many college campuses — including the University of Virginia, Yale University and Princeton University — most of which were violent and unorganized and even resulted in a few deaths among students and professors.

At this time, the students primarily used mischief and pranks as their form of protest, such as when Princeton students set off fireworks in 1817 to demonstrate against their university’s administration. Despite the recklessness of their organization, these early student protests paved the way for improving campus life in the future.

In the 1820s and 1830s the hottest protest topics stemmed from student dissatisfaction with faculty, issues with fraternities, unsatisfactory food options and the suppression of student rights. These early calls to action led to many reforms within U.S. higher institutions that are still present today, such as establishing student governments, expanding the diversity and availability of organizations and extracurriculars, and increasing the transparency between administrations and student bodies.

However, from 1900–1950 there was a shift in the types of issues that drove student activism. In addition to calling for change at local levels, students also directed their efforts toward societal issues. Alongside this, students began to expand their perspectives on the role of colleges as not only existing to educate students but also preparing them to be responsible and engaged members of society. They protested compulsory religious and military obligations and joined labor unions and civil rights marches.

Students even had to fight for their right to protest. The Berkeley Free Speech Movement at the University of California, Berkeley was born to oppose the restrictions set by California universities to limit political activities on campuses. In the 1960s and 1970s, students and faculty became more involved in politics and society as increased accessibility to education, which had been fought for through protest, brought in a more diverse set of voices.

Spurred on by the Kent State University shootings where unarmed protestors were shot by the Ohio National Guard, the student strikes of 1970 were notable, nationwide, concerted walkouts across universities and high schools in response to the Vietnam War. Students from over 900 colleges participated, leading to school suspensions and closures.

Alongside the evolution of protest topics, there was a shift in the manner of protest from the use of violence and gunpowder to written and spoken words. While the focus and manner of activism may have evolved, authors Frank L. Ellsworth and Martha A. Burns assert that the “essence of activism” has remained the same: “an insistent restatement of the need for both societal and institutional reform.”

Student activism at Hopkins

The same issues that have given rise to protests across U.S. campuses are reflected here at Hopkins.

According to a speech delivered by Leslie, Hopkins students held annual antiwar strikes beginning in 1934. Along with students from Goucher College and Morgan State University, Blue Jays would walk out of class to hear speeches from faculty denouncing the war in front of Gilman Hall and Levering Hall. In 1938, protestors even removed two swastikas from Gilman Hall.

Another notable early example of activism at Hopkins began with the activities of the chapter of Students for a Democratic Study (SDS) on campus. SDS is a national organization with chapters across many universities that calls for an end to the American military-industrial complex. In 1969, members of SDS occupied the Homewood Museum, formerly the university president’s office, to demand that the University stop participating in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and military research.

Black student organizations became active at Hopkins in the 1960s. They accused the administration of discrimination in admissions, housing and employment. They demanded increased Black undergraduate enrollment, more representation among faculty and staff, and changes to the curriculum and archives to better reflect their experiences. Students also championed civil rights and held multiple demonstrations in advance of the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

Many students may recall the 2019 month-long sit-in at Garland Hall as one of the more recent campus protests. Another reflection of the past, anti-apartheid protests in the 1980s had led to the occupation of the very same Garland Hall, which students had called “Mandela Hall” as they locked themselves inside.

Women also advocated for their own rights on campus. Though they had been granted admission to the University’s graduate programs starting in 1907, no women were admitted at the undergraduate level on Homewood Campus until over 60 years later. These institutional changes occurred on other college campuses nationwide following the women’s liberation movement. In response to the protests, 90 women were admitted to Hopkins as undergraduates in September 1970.

However, the fight did not end there. Once they arrived on campus, women continued to advocate for themselves. They not only pushed for better facilities catered toward women, such as restrooms and housing, but also called for more representation in student government, sports, The News-Letter, administrative positions and academics, all of which were primarily occupied by men at the time.

With every new generation, the demands and calls to action vary, but, overall, they have the same goal: to fight injustice. Even now, protests on campus echo the lingering issues of the past and continue to call on the Hopkins administration to improve its practices and better serve its students.

However, while past Hopkins protests addressed societal issues, Leslie noted that recent bouts of advocacy have only dealt with campus issues.

“I don't recall any big demonstrations on behalf of Baltimore with the community,” he said. “Hopkins has made a big deal out of engaging the community but not in an activist kind of way.”

He cited the students at Columbia University as exemplifying community advocacy. According to him, they fought for a new gymnasium to be open to their Harlem community rather than being exclusive to Columbia students.

Leslie stressed that students should get involved in activism during their college careers.

“You're not here just to study in the classroom,” he said. “The city is your classroom. The world is your classroom. These are the issues that will determine what our future looks like, and you should have some passion.”

While Hopkins may not necessarily be known for its advocacy compared to peer institutions, it cannot be denied that spaces on campus do exist for students to engage in these pressing issues. The legacies of these movements are felt and seen in the present as young activists today continue to advocate for change.