COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

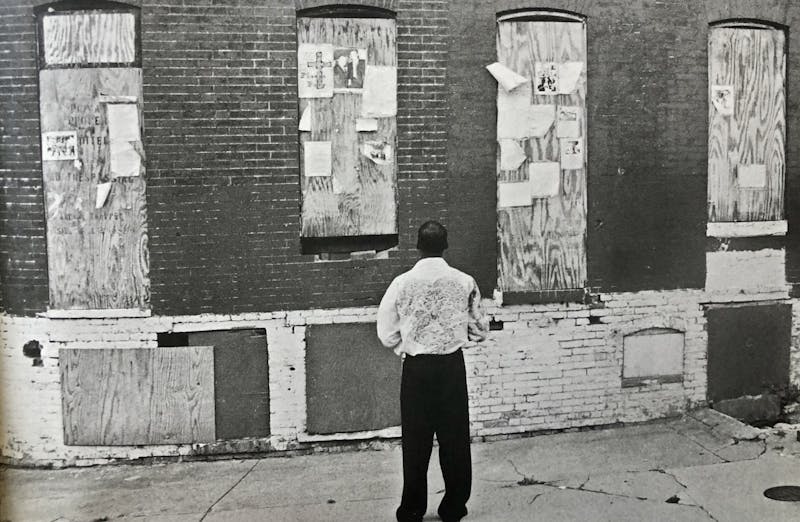

Gresham stands before boarded-up homes that EBDI promised to renovate.

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

Gresham stands before boarded-up homes that EBDI promised to renovate.

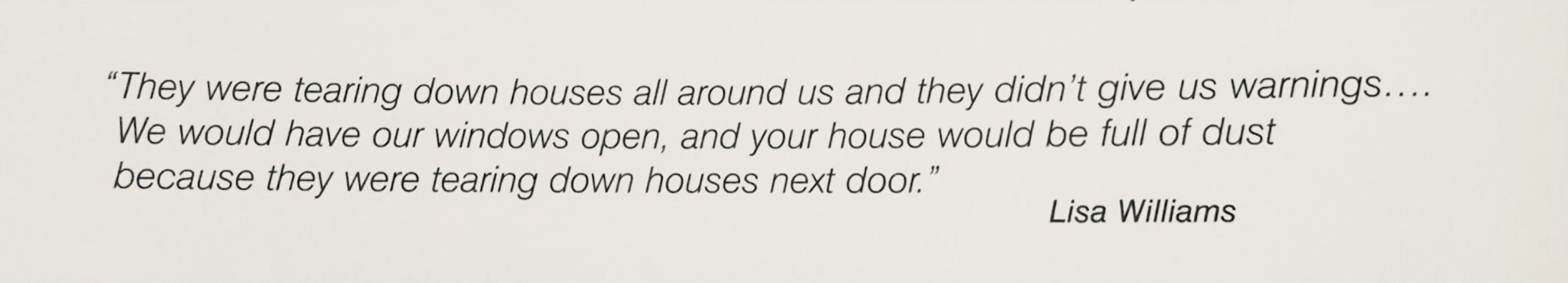

“There were many opportunities to do the right thing, to make a difference for those families whose lives will never be the same. The pain and the horror of the whole process, of being relocated and displaced, of gentrified community — you can’t imagine the pain that goes through your mind.”

These are the words of Donald Gresham, who is president of the Baltimore Redevelopment Action Coalition for Empowerment (BRACE), a nonprofit that aims to promote economic and racial equity in the city, particularly for the former and remaining residents of the Middle East neighborhood.

Located near Hopkins Hospital, Middle East has been renamed Eager Park as part of East Baltimore Development Inc. (EBDI), the most drastic urban redevelopment initiative in recent American history, displacing about 800 predominantly Black and Brown families.

“They were moving people out like cattle,” Gresham said in an interview with The News-Letter.

Hopkins and the City of Baltimore — along with a host of governmental, philanthropic and local groups — comprise EBDI. Its goal is to expand the University’s renowned medical campus into a biotech hub for Hopkins-affiliated students and entrepreneurs. The $1.8 billion initiative is also meant to bring people of all incomes and races into the area through shops, jobs, a new school and a five-acre park.

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

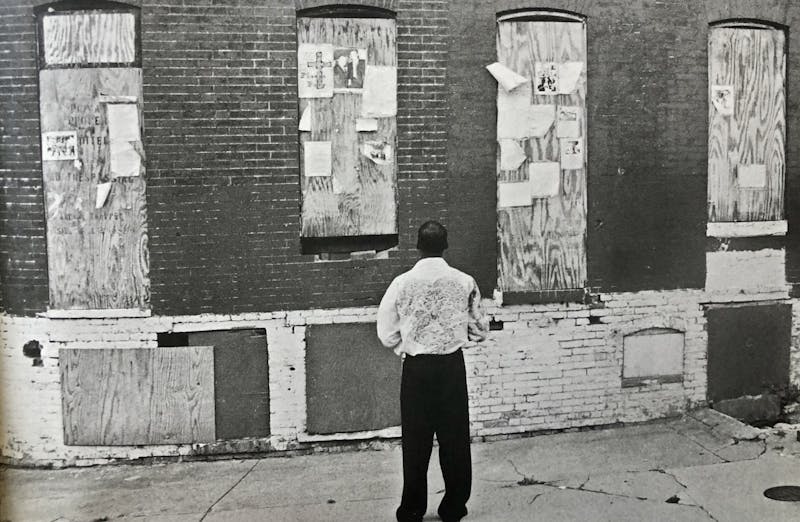

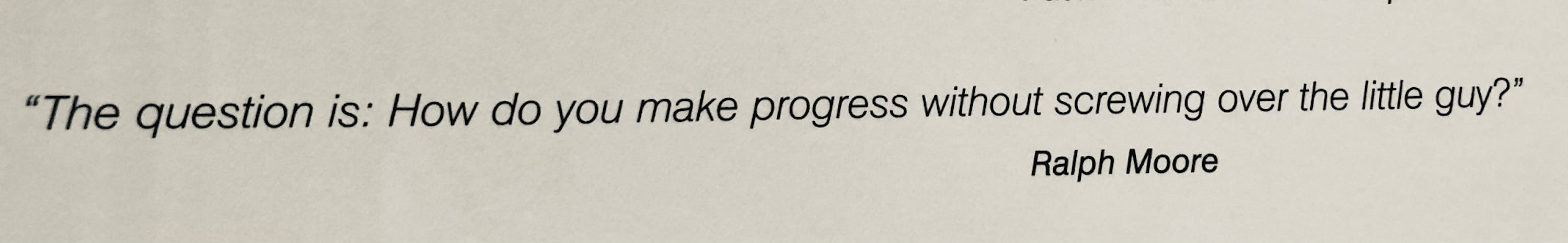

Some Middle East residents first learned that they were being relocated from the news.

EBDI announced its master plan in 2001, revealing that 2000 rowhouses would be destroyed. Although most were vacant, hundreds of people were forcibly removed from their homes through the law of eminent domain, which allows the government to take private property for the benefit of the public after paying just compensation.

In her 2013 book Race, Class, Power, and Organizing in East Baltimore: Rebuilding Abandoned Communities in America, activist Dr. Marisela Gomez notes that “residents were being forced to relocate with no plan for how they could return to benefit from this good.”

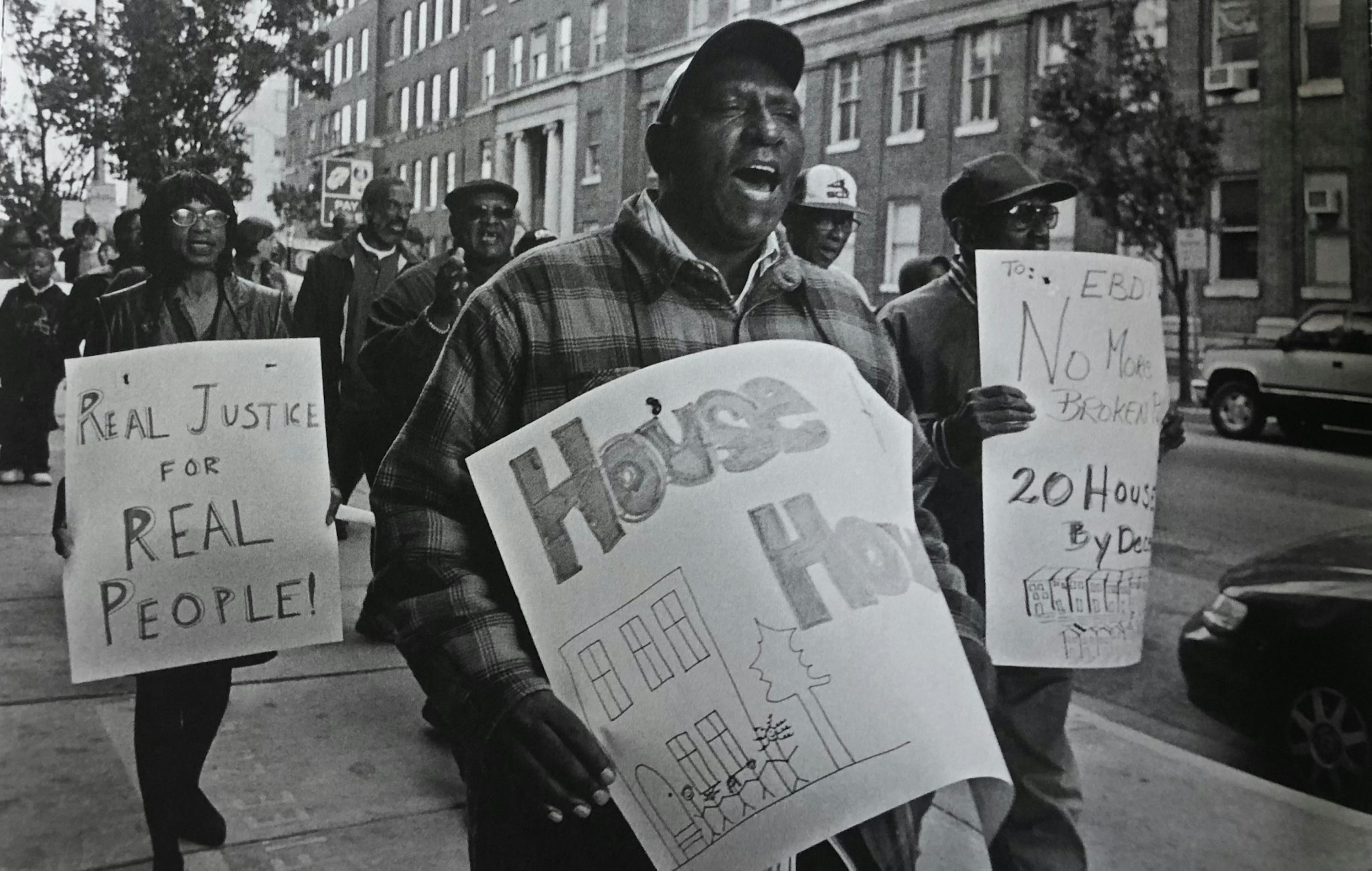

EBDI originally lacked community representation in its planning process. As a result, the Save Middle East Action Committee (SMEAC) was formed. For years, SMEAC fought for fair compensation and relocation terms. The group disbanded in November 2009 and was later replaced by BRACE.

Although displaced residents were promised a path back, the area was a dead zone for a decade and a half due to slow progress. Investment and construction were further delayed by the Great Recession.

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

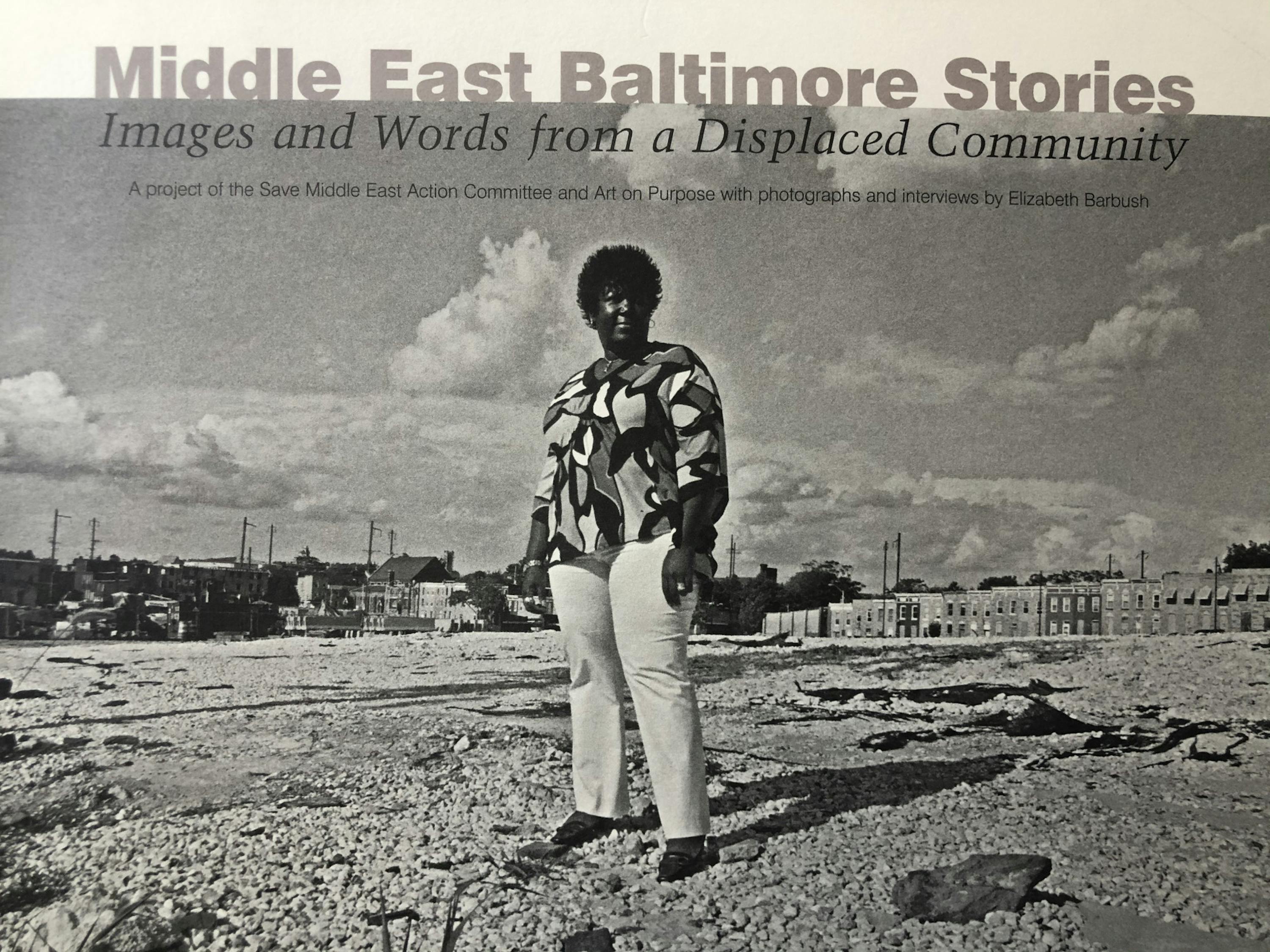

Lisa Williams, one of SMEAC’s founders, visits the empty lot where her home once stood.

At a meeting in 2012, University President Ronald J. Daniels said, “If EBDI fails, then my presidency at Hopkins fails.” Between 2016 and 2018, the initiative finally began taking shape. According to EBDI’s website, the initiative set the highest goal in the city’s history for the participation of minority- and woman-owned businesses in design, construction and equity. EBDI also seeks to cultivate “non-majority participation” at all levels of development, including ownership.

In January 2020, EBDI President and CEO Cheryl Washington said that the project was delivering on its promise to help interested residents return to Eager Park by offering permanent jobs and affordable housing.

Yet Gresham believes that those directly impacted have largely not benefited from this revitalization. Only about 45 families, he said, were able to stay or resettle in Eager Park.

“People were uprooted and displaced for a project that promised a better life,” he said. “In return, they got the most devastated awakening to a project that promised much and delivered very little.”

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Middle East experienced disinvestment, drug epidemics and collapsing home values. Twenty years ago, poverty, unemployment and violent crime in Middle East were double the citywide rate, and average household income was one-third less.

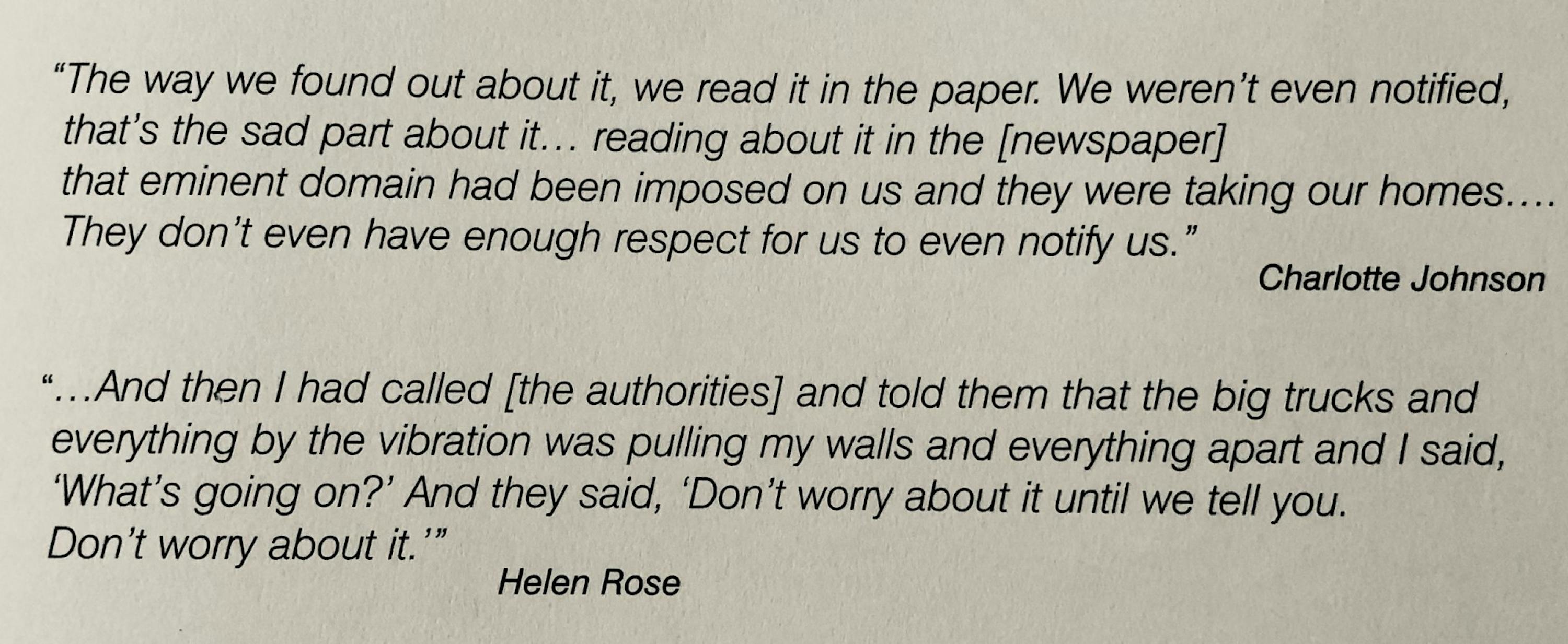

Published in 2009, the book Middle East Baltimore Stories: Images and Words from a Displaced Community seeks to dispute this narrative of despair.

“Anyone driving through Middle East Baltimore before the redevelopment project — noting abandoned homes, a shortage of businesses, and the lack of city services — would likely perceive the community as hopelessly blighted,” it reads. “The network of personal relationships and neighborly support systems that has made Middle East a beloved place for those who live there would be entirely missed.”

Middle East Baltimore Stories is a collaboration between SMEAC and Art on Purpose, which uses art to bring people together around issues and ideas. Elizabeth Barbush, then–program director of the Baltimore-based nonprofit, photographed Middle East and interviewed its residents; her work is featured in the book, which was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a children’s charity and EBDI partner.

At early meetings held by developers, residents found information to be “inconsistent, incomplete, and unclear.” Furthermore, though most residents were informed by mail that they were being relocated, some only found out by watching television or reading the newspaper. This exacerbated the community’s historic mistrust of the Hospital.

COURTESY OF KATY WILNER

During the 1990s, the Kennedy Krieger Institute conducted a controversial study on the health effects of lead paint on predominantly Black children.

Gresham told The News-Letter that he didn’t learn that his home was being acquired until a SMEAC organizer came to his house and told him.

“I didn’t read it in the paper, I didn’t get a letter, I didn’t get any phone calls — all I knew was that they were acquiring my property,” he said. “You would not have known it at all. They had no formal way of letting you know that your property was being acquired and you were going to have to move.”

A 2018 article in the Baltimore Sun describes Gresham, who later became president of SMEAC, as “among those who avoided displacement.” He emphasized to The News-Letter that he and a few dozen others were only able to do so because of years of advocacy.

“I didn’t get displaced because it was designated for me to stay. No, it was more like they dragged out the process, and we had to do a rally and articles and so many things,” he said. “It was a constant battle to get them to hear what we were saying and what they promised.”

Gresham said that SMEAC had to fight “almost day and night” for safe demolition. Middle East Baltimore Stories chronicles how demolition procedures led to property damage and rat infestations, as well as psychological strain that manifested as increased crime and physical ailments like asthma and lead poisoning.

Lead poisoning, which has long afflicted poor and Black youth in Baltimore, is known to decrease cognitive function, increase aggression and ultimately worsen the cycle of poverty fueled by racist policies like redlining.

A 2016 report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation attributes residents’ concerns about lead poisoning to a controversial study by the Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Kennedy Krieger Institute. In 2000, researchers spread fertilizer made from human and industrial waste on the lawns of several homes in East Baltimore. While Hopkins claimed that the fertilizer successfully mitigated lead and that the community had been informed, many activists and lawmakers questioned whether the experiment had exploited poor, Black families.

EBDI used wetting to reduce the spread of lead-contaminated dust during demolition. It also informed and educated residents extensively about planned construction, according to the report.

“The demolition protocols developed for the East Baltimore Revitalization Initiative set a new national standard in the battle against lead poisoning and, more broadly, in the field of responsible redevelopment,” the report reads.

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

Allergies from exposure to dust mite feces can cause asthma, a risk factor for COVID-19.

The authors of the report note that SMEAC had called for demolition to be paused until safety guarantees were implemented.

“Eventually, EBDI and its partners agreed to work toward guaranteeing that demolition would not harm residents and took several key steps to achieve that goal,” the report reads.

Vernice Miller-Travis, a national leader in environmental justice who helped coin the term “environmental racism,” served as a member of an independent panel overseeing the demolition. In the report, she is quoted as commending EBDI’s safety measures.

“I have not seen this level of caution and sensitivity in a community of color or low-income community in the U.S.,” she said. “It sets a new bar about how community development should be done.”

In the 1930s, the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation deemed non-white neighborhoods risky for mortgage support by outlining them in red on residential security maps. To this day, redlined neighborhoods in Baltimore are structurally disadvantaged. Ordinance 610, a 1911 housing segregation law in Baltimore, was a precursor to redlining nationwide. It was in part the legacy of a report initiated by the University’s former president Daniel Coit Gilman.

About a century later, Daniels assumed Gilman’s position in 2009. In 2018, Daniels told The Guardian, “You can make the moral case of why, given the bounty of resources that we have, it’s incumbent on us to share with the city. But the other thing is to make clear that this is an enlightened form of self-interest. It is inconceivable that Hopkins would remain a pre-eminent institution in a city that continues to suffer decline.”

As Baltimore’s largest private anchor institution and Maryland’s largest private employer, Hopkins “seeks to create economic opportunities that are inclusive of diverse people and create wealth for individuals and communities.” This mission statement adorns the University’s web page on HopkinsLocal, an initiative launched in 2015.

Due to the University’s ‘enlightened form of self-interest,’ Middle East’s own neighborhood anchor institutions suffered. For instance, Middle East Baltimore Stories mentions that the Sweet Prospect Baptist Church had been debt-free for decades before it was demolished. Although EBDI helped the church move to a nearby neighborhood, the new building required hundreds of thousands of dollars of renovation.

“The church received a building,” the book reads, “but not a means to preserve the congregation.”

Similarly, Gresham highlighted that people who had been living in the same place for four generations were uprooted by EBDI. During the Great Migration, thousands of Black people came to Baltimore to escape racism in the South and find employment.

“Families came here to have a better life only to later find out that it’s almost like another — I don’t want to call it ‘another Jim Crow’ — displacement of their lives. You put down your roots… and now someone says to you, ‘This area is designated for the rich and famous, and the poor and poverty doesn’t fit in,’” Gresham said. “Can you imagine what that’s like, when you were running away from something and running into something that almost has the same feeling?”

EBDI states on its website that it is helping displaced residents return to what is now Eager Park by “defraying closing and moving costs, narrowing financing gaps” and ensuring that one third of houses are affordable.

According to the website, displaced renters received vouchers “to rent affordably throughout the region,” and homeowners received five times the value of their homes on average, allowing them to “move mostly stable neighborhoods mortgage free.”

However, many residents, Gresham said, already lacked financial stability before EBDI, making them unlikely to return.

In 2018, the Baltimore Sun reported that “just one in 10 displaced residents has returned or plans to, and fewer than a quarter have expressed interest.” President and CEO of EBDI Cheryl Washington told the Baltimore Sun that EBDI hired a consultant to track down displaced residents with whom it had lost touch.

Gresham questioned the EBDI’s ability to do so. Many residents moved out quickly, he said, and have been scattered across the city for almost two decades.

Additionally, though an EBDI survey found that “85 percent of displaced residents said they were better off after being relocated,” Gresham explained why this statistic is misleading.

“You have to imagine the pain and uncomfortableness. First, you move me out like I’m a cattle and then you tell me, ‘Yeah, you can get back, but read the survey,’” he said. “Many people didn’t even respond to the survey because they were devastated.”

Between January 2006 and September 2018, EBDI has yielded 288 hires from Baltimore, only 23 of whom were EBDI-impacted residents.

Since EBDI began, 490 local workers have retained employment by working on EBDI projects. Almost 40% of them are from Baltimore (161 of them from minority groups), and a quarter of them are from East Baltimore (107 from minority groups).

“They came in and disrupted our lives. We thought that money would help to build businesses not only for the community, but by the community and with the community. That didn’t happen,” Gresham said. “The reinvestment money could have been a blessing for so many reasons.”

Gresham added that activists had to push for the public school that was built, Elmer A. Henderson: A Johns Hopkins Partnership School, to allocate more spots to children of color in nearby areas.

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

Activists have condemned the University’s history of gentrifying communities of color.

In a 2019 podcast, Washington described how Middle East residents shaped EBDI in “unexpected ways.”

“Don’t assume that you know what the community needs,” she said. “A lot of what happens is we think we know best, but we haven’t really talked to the community.”

In an interview with The News-Letter, Terrel Askew, an organizer with the Baltimore-based human rights organization United Workers, criticized Hopkins for putting profits over people.

“You don’t improve communities by getting rid of the people who have stuck with those communities all that time,” he said. “How do you rationalize destroying communities in the name of the possibility of people moving in? How does this sit well with you — destroying communities just because you have a relationship with the city that allows you to do so?”

According to Dr. Marisela Gomez, formerly SMEAC’s executive director, EBDI is reminiscent of the Hospital’s expansion in the 1950s. Entire neighborhoods were demolished, displacing Black and Brown communities.

“Instead of addressing the causes and effects of past racist housing and redevelopment practices, this plan was ensuring that race and class segregation continued well into the twenty-first century,” Gomez writes.

Gresham underscored that despite its purported intentions, EBDI failed to prioritize the needs of Middle East residents.

“When you do massive redevelopment projects, you should always include real voices, real conversations and real changes. This is almost like a systemic racism thing going on,” he said. “There’s no way in the world you can do this and be okay with what you’re doing to people of color. It wasn’t for the community at all.”

COURTESY OF ELIZABETH BARBUSH

People march in support of the House for a House program, which promised Middle East residents remodeled homes in exchange for their original ones.