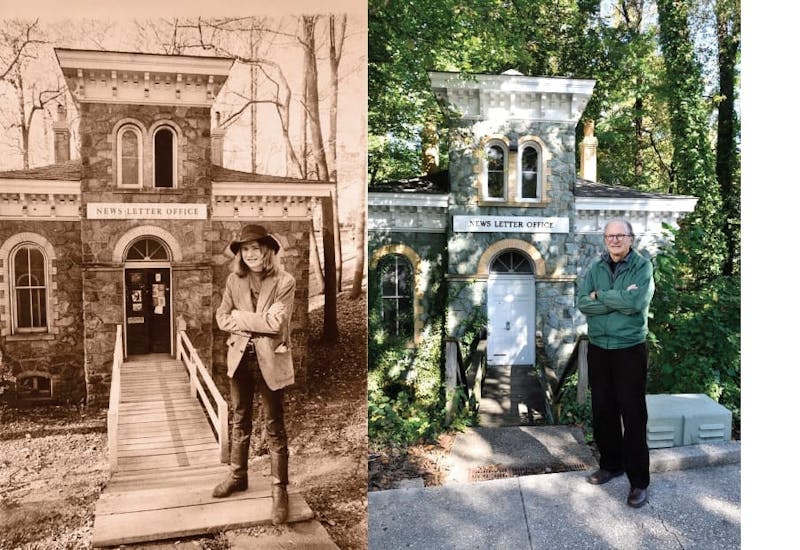

COURTESY OF RICHARD CHILDRESS & WILL KIRK

Hill stands in front of the Gatehouse in 1972 and 2018.

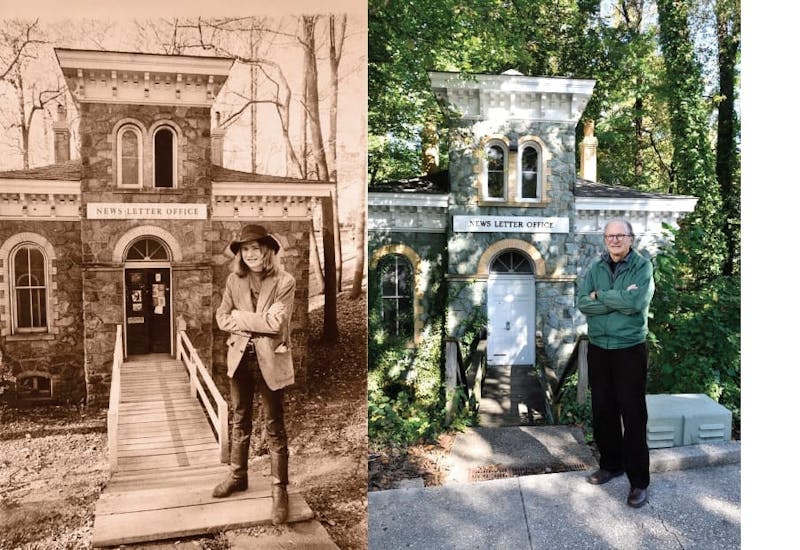

COURTESY OF RICHARD CHILDRESS & WILL KIRK

Hill stands in front of the Gatehouse in 1972 and 2018.

In the fall of 1969, I was in front of Shriver Hall heading for sophomore-year registration when I noticed a tall, shaggy-haired guy approaching.

“You’re coming back down to The News-Letter, right?” he asked.

It was Dick Cramer, the Co-Editor-in-Chief. It felt special that he had singled me out for such attention as I had only written a couple of stories as a freshman. Later I learned that any editor would do the same for a warm body who might stumble into the Gatehouse.

My Hopkins years — 1968 to ‘72 — were tumultuous times for colleges and for the country. The political eruptions caused by the Vietnam War, combined with the cultural tumult of sex, drugs and rock and roll, would upend so many assumptions about the world we were about to enter as adults. I certainly had my share of uncertainties. After Cramer asked, I went back down to the Gatehouse. And it wasn’t long before many of those uncertainties disappeared; it was clear that this was where I belonged.

As it turned out, Cramer needed all the help he could get. The year before, Co-Editor-in-Chief Bruce Drake had almost single-handedly turned an eight-page mushy publication into 20 pages of solid weekly journalism. Now Cramer planned to add a Tuesday edition.

The Gatehouse looked pretty different then. The walls were covered in graffiti and a collage of pasted-on pictures and articles and whatever. Most everyone smoked, and when a rookie asked what to do with his dangling ashes, a veteran pointed to the message scrawled above the front door: “The World is Our Ashtray.” While in many ways it was even more tumultuous than the campus next door, the Gatehouse was our refuge from the craziness, a place we could call our own while we sat at our typewriters and tried to make sense of it all — or at least to fill the paper with somewhat legible copy.

My big break came in November 1969, when the editors trusted me with covering the huge anti-war Moratorium demonstration in Washington. I took off in my balky Karmann Ghia and spent Friday night marching from Arlington Cemetery to the White House with a candle and the name of a soldier who had died. Then — after sleeping on a church pew — I spent Saturday with hundreds of thousands on the Mall.

My press pass got me a front-row seat for the speakers and entertainment — Pete Seeger; Arlo Guthrie, Peter, Paul and Mary; Richie Havens — and I was having a great time, but duty called. There were reports of trouble around the Justice Department. Finding nothing but confusion and the smell of tear gas and with a car that wouldn’t start, I hitched a ride back to Baltimore and to the Gatehouse. My story ran as a two-page spread in the middle of an early Tuesday edition of The News-Letter.

More than stories, I remember the remarkable group of people, all of us working our butts off and having a great time, laughing a lot as we went about this serious business of figuring out what this thing called journalism was. One of our amusements was writing headlines. In one issue, they were all lyrics from Bob Dylan songs. Alliterations on sports stories became a particular late-night challenge. “Hapless Hopkins Hoopsters Hobbled/Cagers Crouch for Coming Contest” remains a favorite.

For most, it must be admitted, classes were an afterthought. Incompletes were common. In those pre-computer days, papers were often typed out without the benefit of a first draft, in the wee hours, after work on The News-Letter had been finished. At the end of my sophomore year, we had wrapped up the last issue when all hell broke loose with the invasion of Cambodia and the shootings at Kent State and a subsequent strike over military recruitment at Hopkins. It was back to the Gatehouse. We put out three issues that week, exam week.

Among the remarkable group of people was my classmate Mark Reutter, Co-Editor-in-Chief as a junior. While the rest of us thought we were ending a war and changing the world, Mark was writing carefully researched stories about the University budget that were instrumental in eventually bringing the presidency of Lincoln Gordon to an end. That happened on a Friday just as Art Levine and I took over as Co-Editors. We had a two-page special out the next day. Reutter went on to the Baltimore Sun where he uncovered a major fundraising scandal in the Catholic Church. Today, he torments Baltimore’s poobahs at the online Baltimore Brew.

Reutter’s Co-Editor Ted Rohrlich assigned the first story I did as a freshman. He had a career at the Los Angeles Times as an award-winning investigative reporter. When, in my junior year, I told my friend Howard Weaver that we were getting credits for working on the paper via a friendly Writing Seminars professor, he came down to the Gatehouse and got hooked, too. We once interviewed Howard Cosell when Monday Night Football came to town for a Colts game. Weaver won two Pulitzers with his hometown Anchorage Daily News and retired as head of news for the McClatchy chain in Sacramento.

Cramer — no longer Dick, now Richard Ben — won the 1979 Pulitzer for International Reporting at The Philadelphia Inquirer and had a long career as a magazine and book author, including writing What It Takes about the 1988 presidential race, considered by many to be the best book ever written on American politics. He died too young in 2013. President Joe Biden, one of the subjects of What It Takes, spoke at Cramer’s memorial service at Columbia University, where he got his master’s.

As for me, I spent 35 years at the Baltimore Sun and Evening Sun, doing everything from TV critic to foreign correspondent, covering Nelson Mandela’s election as president of South Africa in 1994 when my editor was fellow News-Letter alum Robert Ruby. I met many remarkable journalists during those years, but never a better crew than the one I shared the Gatehouse with 50 years ago.