Your life is recorded in the millions of trillions of muggy fingerprints you leave behind in every decision you make: Innermost secrets spill out in the non-privacy of your internet searches, the political party you voted for last election and the text you sent your mom yesterday.

The fingerprints that make up my life only click into place when I see the novels, textbooks and architecture tomes of my past swirl and swim to superimpose over the moments they mark in my life; words and emotions pressed and preserved between sticky pages. I pick out a few volumes from where they hover over my timeline and set them out neatly onto the table in front of me. I turn them so you can see them.

We start with From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg. It has that scratchy, browned paper of a childhood paperback. Our protagonist solves Michelangelo mysteries and hides from security guards in bathroom stalls. I am dazzled by the idea of running away to live in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. After this book, I keep meticulous track of my loose dollar bills, of any spare change I can get my hands on in preparation for the possibility of stowing away curled under a bus seat to reach New York and sleep surrounded by works of art.

When I read Chew on This by Eric Schlosser and Charles Wilson, the grotesque imagery of poultry farms makes me swear off chicken nuggets — but only the ones from McDonald’s.

Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie is such a silly and terribly clever book that it cracks my head open to the understanding that I can write, too.

Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s The Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life can only be described as a generous slathering of detail. True to its encyclopedic format, Rosenthal’s life is cut into entries and categorized alphabetically rather than chronologically. We see multiple pages worth of her parking tickets and know she loves the palindrome “WonTon, not now” and from that point on I think about her entry for the word “love” so often it becomes my own truth.

Mirage by Jenn Reese makes me want to learn to scuba dive. It drives me to read Darwin.

I didn’t consider myself a science person until I read The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher by Lewis Thomas. The interlocking of each phrase with the next sounds like an array of facts splayed over sheet music, the words rhythmic in both logic and diction. I reread these essays multiple times throughout high school.

As I have aged, my commitment to reading has fluctuated, which is perhaps a telling reflection in and of itself. To rescue and satiate my reading, I have started revisiting my old books.

It was a shock when the brilliance of Forty Rooms by Olga Grushin seemed to shrivel the second time I opened it. I stopped calling it my favorite book. Yet, when I look back, I only remember the first read. The prodding thrill, the cancer scare and Russian ghosts, the book angled to catch the light of the sparse streetlamps before the car is plunged into semi-darkness once again.

I picked up To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf for the first time during quarantine. Her writing was an exercise in white water rafting, plunging from one character’s inner world to another, direction dictated by the tiniest shift of a rock. I imagined myself standing in an empty house with the characters echoing off each other in the same way I stood still in my room around a changing world. Upon rereading, I disagreed vehemently with my past self’s annotations. No, I no longer feel the need to punch Mr. Ramsey in the face. I no longer take sides in their conversations, choosing instead to simply chew on the words and see what they taste like to me.

It is strange to revisit a book and find something new, or stranger yet, to not see what was there the first time.

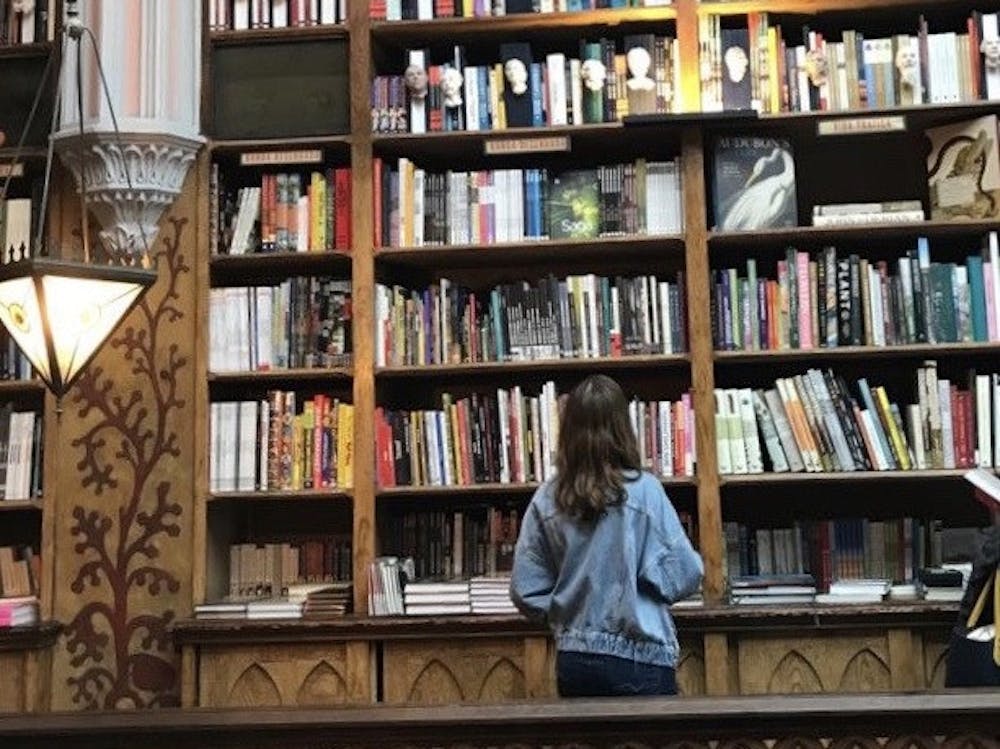

Looking through my favorites, it’s easy to think of my bookshelf as a biography. In reality, it is a mirror. Each time you revisit a book, a small trace of yourself gets snagged between the lines, the smudges accumulating like heights marked on the walls of a childhood home. Blocks of text and ink are static, but even as they hold the same greasy fingerprints from years ago, those marks flicker if you stand in front of them for long enough. Squint your eyes, tilt your head slightly, and you’ll see the tally marks burgeoning and compressing to form the shimmery reflection of your face as it is now.

Arantza Garcia is from Miami, Fla. majoring in Behavioral Biology and Neuroscience.