Despite the hardship the COVID-19 pandemic inflicted on many globally, it sparked immense progress in rapid testing for infectious disease: One could take a test quickly at home to determine whether they were infected, accelerating disease detection, treatment and recovery. Such innovation was partially championed by the Johns Hopkins University Center for Innovative Diagnostics for Infectious Diseases (JHCIDID).

Among the many physicians and scientists within the center is Dr. Yuka Manabe: a professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the School of Medicine. Her research aims to develop and globally distribute rapid diagnostic tests for a variety of infections, specifically sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). In an interview with The News-Letter, Manabe explained her work and her interested into why she started researching rapid diagnostic tests.

Manabe completed her internal medicine residency and infectious disease fellowship at Johns Hopkins Hospital, continuing her work in molecular biology and infectious disease research. However, it was not until 2012 — after having lived in Uganda for five years and been exposed to the challenges of extreme diagnostic indeterminacy in the country — she made rapid diagnostic medicine and the development of point-of-care tests the centerpiece of her work.

“You might have a patient who comes in with a fever, and you don't know what's wrong with them. I think I was meant to search for diagnostic certainty and targeted treatment that can save lives,” Manabe said.

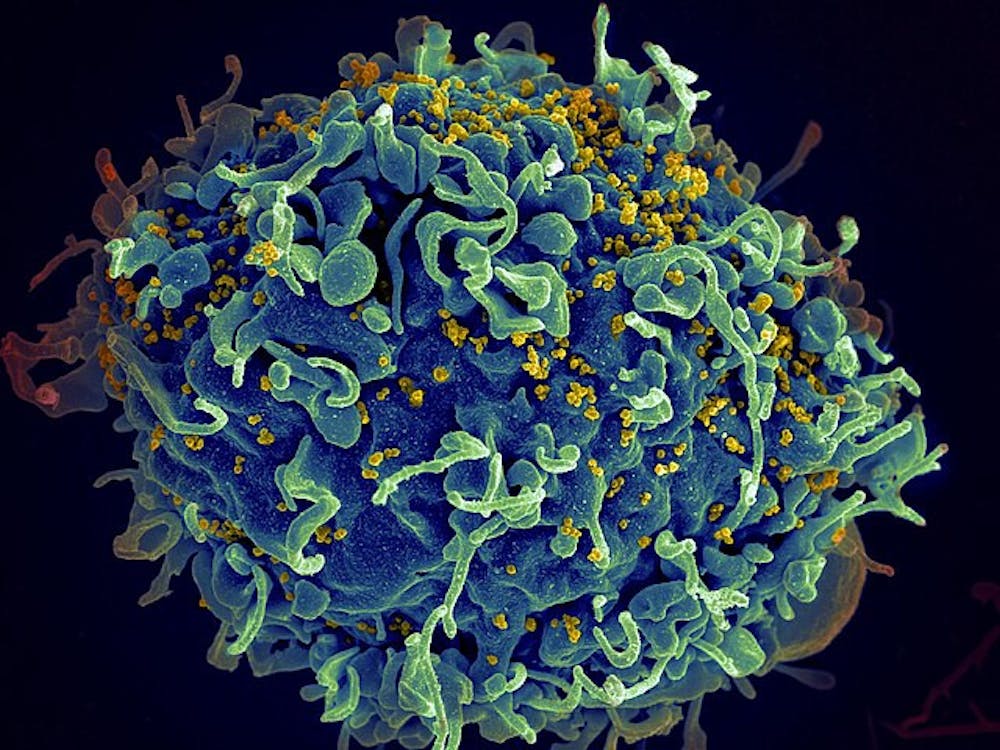

In recent years, Manabe’s research has aimed to deliver the diagnostic efficiency the world saw with at-home tests for COVID-19 to many STDs, including HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis and many more.

While the JHCIDID works to manufacture its own tests, it also collaborates with external developers and examines to examine the efficacy of those tests through a process called tailored benchtop evaluation. Manabe further explained the procedure.

“Essentially, we can give the companies feedback, potentially saving them money and accelerating development,” she elaborated.

With creating tests that can diagnose patients with STDs within the comfort of their own home being a sensible idea, why is it only being pursued now when STDs have long ravaged communities around the world?

“Part of the problem is resistance from public health officials. When you do a test on yourself. Nobody knows what the results were. You only know the results. This aspect of privacy attracts more people,” she stated. “However, what public health officials don’t like is they don’t want to give people self-efficacy because they want to know how many people they’re testing and how many people tested positive. They want all that data.”

Manabe, however, believes this disconnection between public health researchers and research subjects to be a worthy sacrifice.

“I think giving people the possibility of self-testing at home will mean more mean people will get tested, meaning more people get treated, get cured and not transmit their condition to others,” she argued.

Even if public health officials were to come around, that would only ease the resistance slightly.The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been highly reluctant to approve self-tests, citing concerns that the public may misuse them or unintentionally cause harm, Manabe explained.

Such was the prevailing viewpoint of the regulatory agency up until four years ago when COVID-19 ravaged the U.S.

“One of the very few beneficial things about COVID was that the FDA realized people could actually test themselves and do it accurately,” said Manabe. “The FDA has changed their tune a little bit on self-testing, as long as the actual test performs well.”

With difficulties from regulatory agencies beginning to subside, one challenge remains: affordability. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, self-tests for HIV mainly consisted of lateral flow tests, similar to pregnancy tests where one gets a line indicating their status. The medical world is starting to lean more towards a molecular approach, considering the increased specificity and consistency in results it offers.

However, the issue with molecular tests is that they’re expensive, costing about twenty dollars. Lateral flow tests — like pregnancy tests — cost as little as one dollar. On the other hand, Manabe stated that these at-home tests might still be more affordable than standard testing.

“People are willing to spend that because just to walk into a clinic for an individual with average income to get examined for an STD is going to cost them around $90,” Manabe stated.

Additionally, Manabe’s work is especially outstanding since it matches the desires of a society in transition where doctors and researchers are working to make sure their research caters to millennials and Generation Z. This fact contributes to the increased need for rapid diagnostics.

“If the younger generation had the chance to do everything online or through text, they would prefer that to talking to a human being in person. This is why things like self-tests really appeal to our society now since it requires limited interpersonal interactions. We’re sort of entering a DIY time,” she noted.

The work of the JHCIDID is making extreme progress, and Manabe hopes it will lead to increased health equity and efficacy in the upcoming years. She hopes the see commercially available tests for common infections, believing that that would increase health equity.

Diagnostic certainty is incredibly important, as someone being conscious of what disease they have is critical for recovery.

“Knowing is the first step to curative treatment and not transmitting the specific disease to others. But also, if an individual has HIV or a condition that can’t be cured, at least they could more quickly be put on a treatment that would decrease their risk of dying from a compromised immune system,” Manabe affirmed.

Despite the complicated nature of this research, one thing remains clear to Manabe and the JHCIDID.

“The same access to tests and innovation is the goal,” she concluded.