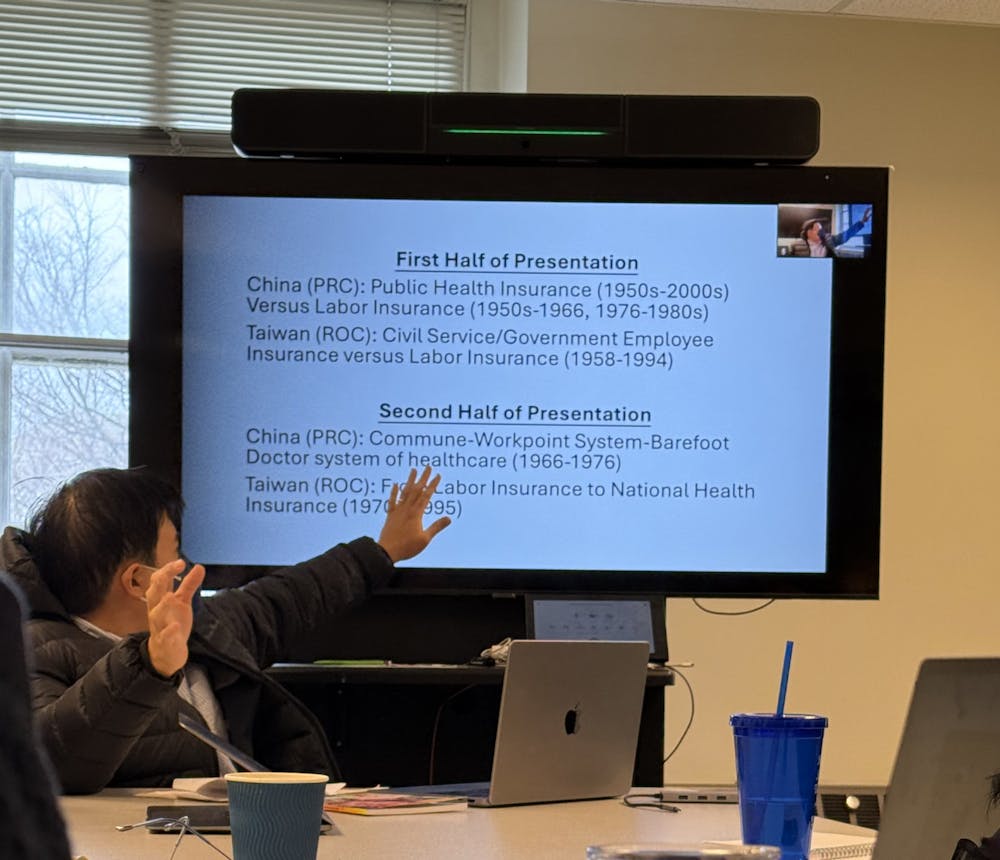

On Tuesday, Feb. 19 the East Asian Studies Department hosted an event titled “Comparative History Matters: Health Insurance, Medicine, and Ideology in China and Taiwan” as a part of their Spring 2025 Speaker Series. The event featured Wayne Soon, an associate professor in the Program of the History of Medicine in the Department of Surgery at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, who discussed the political and social dynamics that have shaped health care policy in China and Taiwan since the end of the World War Two.

Soon opened the conversation by listing four myths about Chinese and Taiwanese health care systems that can lead to false comparisons between the two nations and false narratives of civilian access. These myths include the that the Taiwanese public health care system was a latecomer, notion that health care is free in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), that democratization necessarily leads to universal health care, and that actuary science was the only facet instrumental to medical development in Asia.

Soon, however, stressed the importance of a comparative perspective on the Chinese and Taiwanese health care systems.

“[Through comparison] you can see the unique aspects of ideologies that shape both China and Taiwan,” he said. “Architects of the PRC labor insurance claimed they created a system that was superior to the nationalists — they will directly compare their own experience. Actuary science experts that went to Taiwan often drew their experiences from the United Kingdom and Japan.”

He then gave an overview that historically in both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China, those who were considered supporters of the current administration — in China, the Communist Party, and in Taiwan, the Nationalist Party — were afforded better health insurance than those who were working in non-political roles.

“It is my main argument today that the communists and nationalists privileges their own supporters by making the public health insurance program and the government employee insurance program more accessible and more equitable than their respective labor insurance programs,” said Soon.

Soon described that in Taiwan, the civil service insurance program differed from the labor insurance program — while the former covered both inpatient and outpatient care, the latter only covered inpatient care and hospitalization at its inception. He contended that the public or labor coverage within Taiwan was inadequate during this period and had several exemptions to care. Laborers were forced to rely on a system known as menzhendan, through which they received a limited number of consultations a year, pending approval from their supervisors.

“The menzhendan system required Taiwanese laborers to jump through several hoops to access care,” he said. “It was revealed that some companies refused to sign the menzhendan because they never bought labor insurance for their employees in the first place, even though it was mandated by law.”

Soon stated that during the same period, the Chinese government touted public and labor health insurance as equal, but the reality for laborers looked very different.

“In China, benefits were calculated based on the number of years spent working. This is to discourage people from changing jobs...The years that Nationalist lower-ranking officials served before 1949 were not counted under the new communist regime, which meant that labor insurance benefits were unequal from the point of inception,” Soon said.

He also mentioned that employers in some cases dropped health care coverage for employees whose spouses were on a different public health insurance program.

As some Chinese patients began to abuse the public health insurance system, giving medication receipts to friends and family and purchasing seemingly unnecessary medication, local officials blamed physicians instead for the abuses. Soon described this as an instance of favoritism of political supporters on behalf of the Chinese government.

Soon then shifted to a discussion of post-1970s reform, outlining the differences in Chinese and Taiwanese health insurance system, despite their shared goal of universal health care.

“Taiwan was increasing democratization and pushing for truly universal healthcare, while in China, they tried to do the same thing through tackling the supply-side issue during the Cultural Revolution...and trying to increase the number of barefoot doctors,” he said. “The outcomes were quite different, though. In China, they abandoned the project and China became a market based insurance [in the immediate post-reform period]; in Taiwan, they really held on to universal health care.”

An integral part of Chinese health care was the introduction of a work-points system. Workers were afforded points based on labor hours, which they could exchange for goods and services. The barefoot doctors system was instituted shortly thereafter and was meant to expand access to medical treatment. The system sent young people, who had received only a few weeks to a few months of training, to the rural area to learn from local doctors. Each of these programs were maintained by the Communist Party until the reform and opening period in the 1980s.

“Many of these barefoot doctors were undertrained and inexperienced. They were usually not reimbursed or paid through labor insurance funds or by the central government; rather, they were expected, like many Chinese, to receive most of their remuneration through the work points system,” Soon said.

During the 1990s, Taiwanese public insurance improved as universal health care became the focal point of local advocacy and the government signed the National Health Insurance program in 1995, establishing a nationwide health insurance system. In China, the lack of reform following the reform and opening period prevented citizens from accessing quality care, and China fell short of its common goal of developing an operable and equitable insurance system for some time.

“As China and Taiwan continues to grapple with health insurance reforms engendered by the long shadow of authoritarianism, my contention is that their desire to spend as little as possible on health care while seeking to deliver more health and resources remains unchanged,” Soon concluded.

The event was attended by numerous faculty members and students, both graduate and undergraduate, who hoped to gain awareness about the complexities of the health care systems in each country through comparative analysis.

In an interview with The News-Letter, freshman Nicolas Poliak discussed his interest in the history of health care in China and Taiwan.

“I was interested in hearing about discrepancies in health care equity abroad,” he said. “I was particularly curious about Taiwanese and Chinese health care development, given my interests in medicine and political science.”

In an interview with The News-Letter, freshman Leo Liu discussed the insight he gained from the lecture.

“I learned a lot about the health care systems in China and Taiwan and how political and sociological comparative analysis might shed light on the intricacies of their development,” he said.

Editor’s Note, 2025: This article has been updated to better represent Dr. Soon’s discussion of the Taiwanese and Chinese health insurance systems

The News-Letter regrets this error.