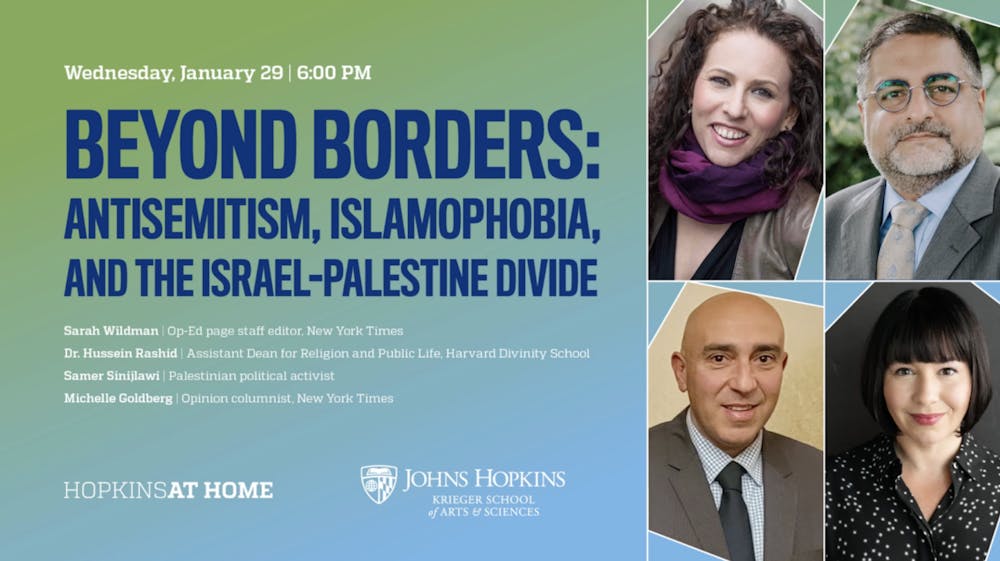

On Wednesday, Jan 29, the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences (KSAS) and Hopkins at Home hosted an event titled “Beyond Borders: Antisemitism, Islamophobia, and the Israel-Palestine Divide” as the first virtual panel discussion in their ongoing series “Conflict in the Middle East: Context and Ramifications.” During the event — hosted by Director of the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute William Egginton and moderated by New York Times editor Sarah Wildman — participants engaged in conversation about how religious biases are defined and how they affect the prospect of peace in Israel and Palestine.

Eggington described Hopkins at Home’s motivation for hosting the event and selecting its panel participants in an email to The News-Letter.

“The conversations began with Johns Hopkins faculty, and we wanted to broaden the conversation by inviting a range of speakers who would be able to speak to the multiple facets of the conflict: its historical roots, current dynamics, and potential pathways to peace,” he wrote. “In selecting speakers we aimed for a balanced discussion with experts who could represent diverse viewpoints and dialogue in a productive way.”

The event was moderated by Wildman, who began the conversation by discussing antisemitism and Islamophobia’s historic roots. The purpose of the discussion, she described, was to investigate how these prejudices have evolved following the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and related current events and how they appear and impact public discourse on these issues.

The floor was then opened to Hussein Rashid, assistant dean for Religion and Public Life at Harvard Divinity School, Samer Sinijlawi, a Palestinian political activist joining the call from Jerusalem, and Michelle Goldberg, a New York Times opinion columnist.

The speakers began by establishing what definitions of antisemitism and Islamophobia are best for understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and its global implications. First, Goldberg introduced the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, a document designed to define the limits of antisemitic speech and conduct.

“The Jerusalem Declaration basically tries to separate out anti-zionism from antisemitism, and it defines antisemitism as discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews, or Jewish institutions as Jewish,” she said. “A central part of classic antisemitism revolves around the idea as both epitomizing evil and having some kind of almost supernatural power.”

Sinijlawi agreed, claiming that it is best to define antisemitism and Islamophobia as “racism against religious groups,” rather than delving deep into the specifics of defining these prejudices. Rashid added that the phenomena of antisemitism is supplemented by the long-standing theory of Aryan replacement by Jews, citing the public response to the 2017 Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia where crowds chanted “Jews will not replace us” as an example of the ongoing impact of this harmful rhetoric.

“Another theme is false or weaponized and distorted accusations of antisemitism,” said Goldberg. “Elon [Musk] has a long history of antisemitic insinuation… whenever he does something that I think is antisemitic by any yardstick, typically the next step is to say ‘but he supports Israel. What I think we increasingly see is support for Israel being used as an alibi for expressions of genuine antisemitism.”

Shortly thereafter, Wildman asked about the future of a two-state solution, and whether it might quell antisemitism and Islamophobia globally. Sinjawi responded to this question, suggesting that the formation of two states may be a reasonable solution to this conflict.

“There is real fear in the hearts of Israelis, and it comes from a long history of antisemitism… there is also a real need for freedom on the side of Palestinians, and these make up the DNA of the conflict,” said Sinijlawi. “We must learn to accommodate both. The only way to treat this conflict is to end this conflict, and I don’t see any other way of ending this conflict other than the two-state solution. The one-state solution will prevent the basic need of the Jewish person to live in his own Jewish state.”

The event then transitioned to a discussion of interfaith dialogue and solidarity among Jewish people and Muslims through a potential two-state solution.

Rashid suggested that it is the authority figures on each side who prevent Israelis and Palestinians from uniting, perpetuating the mistreatment and mischaracterization of both groups.

“Solidarity is more necessary than ever,” he said. “We must question, who is our oppressor and how are we being oppressed? Who is benefitting by keeping us separated?”

According to Sinijlawi, such unity has been impacted by outside forces. He claimed that worldwide protests have diluted the perceived interest of each group, suggesting that those who rally on either side are misled in using language and other demonstrations of hate and expulsion. He went on to conclude that Palestinians and Israelis can be the solution to each other’s security and social issues instead of continuing to be a source of common distress. He noted that the best route for unity is rallying behind their common interests, including the release of Israeli hostages, the demilitarization of Gaza and the continuation of peaceful political negotiations.

Sinjawi then discussed what qualities new leaders of Israeli and Palestinian states would need to ensure long term peace, prompted by a question from Wildman.

“New leadership must give a lot of priority to the fight against incitement and hatred,” he said. “Like a pandemic, you cannot fight it on one side and not the other side. It will come back.”

Rashid added that peacemakers must consider the religious implications of a two-state solution. Sharing a land that is sacred to multiple groups of people heightens the complexity of a peaceful interfaith state, he noted, especially given that both groups in question have lay claim to Jerusalem.

The panelists then took a comment from the audience regarding Israeli security and future political negotiations on both sides of the spectrum, which introduced a discussion on Hamas. Sinijlawi suggested that both sides of the conflict have engaged in morally damaging actions, which has exacerbated the conflict.

“On the 7th of October and during the war afterwards, it has been proven that this conflict has damaged our morality — we are both ugly,” he said. “We started believing that everything is permissible. Coming to Hamas, whatever we do there will always be some extremists that are part of our political life. The mainstream should keep these extremists on the side and control them, not the opposite. The same thing should happen in Israel.”

He went on to suggest that moderation and deradicalization are the keys to maintaining peace, and can only be achieved if Palestinians have a partner in Israel.

The discussion closed with another question from a student in the audience, who asked how students should navigate conversations and criticism about Israel without being labeled antisemitic.

“It is antisemitic to demand Jews specifically to disavow Zionism as a prerequisite for entry into educational and public spaces,” Goldberg responded. “To approach this, especially as a student, you need both a measure of courage but also a measure of generosity.”

In his email to The News-Letter, Egginton described this event’s potential benefits for the student population and greater Hopkins community.

“Our goal is to enrich viewers’ understanding of what is a very complex situation, to foster a deeper understanding of these issues and what they mean for our communities in both a global and local sense,” he wrote. “This applies to our entire audience, but we are especially focused on our students who are also thinking deeply about what productive civic engagement looks like. We are very fortunate that Professor Steven David has agreed to offer a course on the series and that those students who wish to do so can explore these topics further.”