Bob Dylan is an enigma. Despite being a towering force of American culture, he has always defied easy interpretation, too slippery to fit into categories or expectations. So, do we really need a Bob Dylan musical biopic? The genre is synonymous with clichés and unoriginality — notoriously squeezing complex lives into generic, done-to-death narratives.

Dylan, of all figures, demands an unconventional approach. Films like Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There understood this, experimenting with the genre by casting six different actors to embody various stages of Dylan’s life. James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown follows a more traditional biopic structure, focusing on Dylan’s early years in the 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene, his fraught personal relationships and his controversial transition to rock music.

While A Complete Unknown is better than the usual musical biopic fare, it still doesn’t quite match the complexity of its subject. If you are going in seeking a greater understanding of Dylan’s art and the culture around him, you will likely leave with a handful of half-answers made up of easy half-truths. It doesn’t commit fully to any particular take or storyline about fame, artistry or romance, instead offering a collection of Dylan-adjacent platitudes about what it means to be an artist.

Many tropes are run through in formulaic fashion: Dylan is the “difficult genius” whose douchebaggery becomes an obstacle for everyone but himself. He is the rebellious artist defying expectations; the reluctant visionary that resents fame.These traits are undoubtedly true of Dylan’s persona, but the film doesn’t go much further than simply repeating them.

A Complete Unknown’s greatest achievement is Timothée Chalamet’s electric performance as Bob Dylan. Despite possible skepticism about casting such a polished, mega-superstar for a provocative and jagged figure (an ironic choice for a film titled A Complete Unknown), it is undeniable that Chalamet transforms wholly into Dylan. He embodies his wiry physicality and his peculiar mannerisms, giving off a magnetic but also bristly quality that keeps us detached at a curious, orbiting distance. Most notably, Chalamet sings all 40 of the songs live on his own, a musical performance that reflects equally on Dylan’s masterful songwriting and on the star’s devotion to the role.

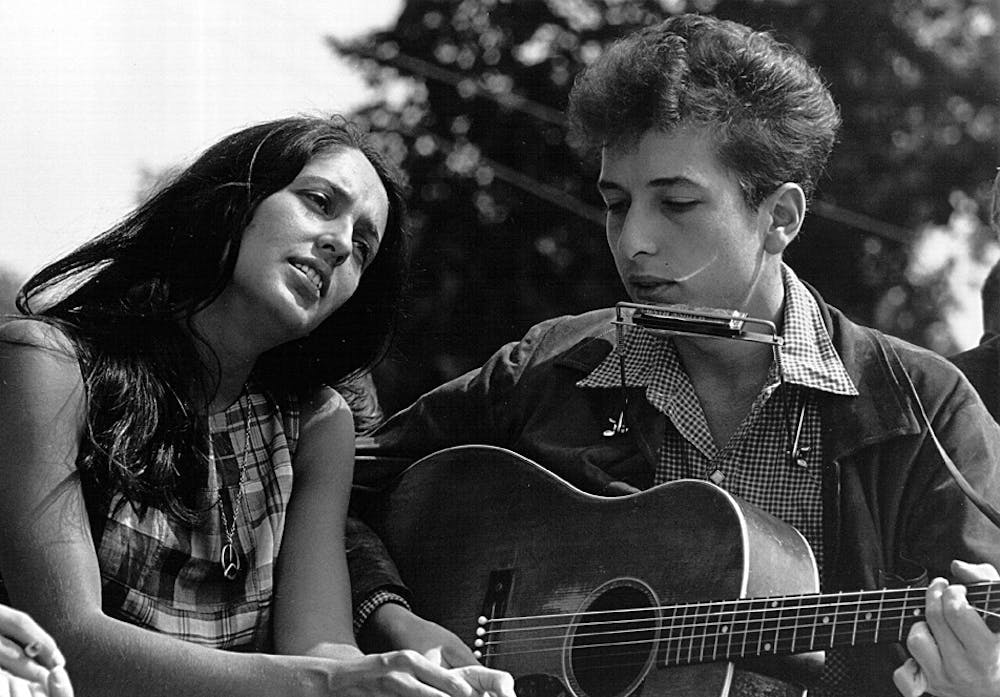

The supporting cast delivers as well. As Pete Seeger, Edward Norton conveys an earnest wistfulness that acts as the film’s moral center, while Monica Barbaro carries a keen boldness as the “Queen of Folk,” Joan Baez. Both have been recognized with oscar nominations for their roles.

However, these performances often convey a level of complexity and nuance that is missing from the actual writing. Characters often feel limited to singular, repetitive reactions to Dylan’s behavior, done in order to make some clichéd point about what it’s like to be around a genius.

The female characters are great examples of this. Sylvie Russo, based on Dylan’s real life partner Suze Rotolo, is lifted entirely off of the textbook jealous girlfriend archetype, as she dawdles helplessly behind Dylan with yearning eyes, erasing Rotolo’s major influence on Dylan’s artistry and political awakening. And for an artist whose songs explored love and romance so often, there is surprisingly not much of it to be seen between the two.

Joan Baez fares better, but when she’s not singing, she’s relegated to a moody, irritable presence, a lesser artist overshadowed by Dylan. As the film progresses, Baez, Seeger and the folk scene at large, increasingly become irrelevant relics of a bygone era, stepping stones that Dylan is destined to outgrow rather than equals in their own right. Meanwhile, Dylan’s betrayals and duplicities are handwaved too simply as inevitable byproducts of his amazing genius, without enough pushback or interrogation that would allow for an interesting take on the dark side of fame.

Ultimately, these relationships arrive at the tired conclusion that “artists can be difficult to love.” Such a platitude feels inadequate for someone like Dylan.

The main conflict of A Complete Unknown is Dylan’s controversial transition from folk to rock, but the film doesn’t give this pivotal moment its due weight. Instead of presenting it as a fraught break from folk’s countercultural protest roots it’s reduced to a straightforward stylistic upgrade: trading acoustic simplicity for the coolness of electric instruments.

This simplification stems from the film’s lack of interest in the 1960s’ context; civil rights protests and news broadcasts appear as mere decorative backdrops, sidelining the folk movement’s role as both a response to and an influence on the world around it. As a result, folk is conveniently dismissed as an artistic dead-end, clung to only by caricatured purists, making Dylan’s departure too obvious to be at all interesting.

While the film touches on the theme of artistic freedom versus artistic responsibility, it doesn’t quite get to the heart of either the folk scene Dylan leaves or the rock scene he enters, making it hard to grasp what’s at stake in either direction. Instead, it settles on the oft-repeated refrain that artists must “follow their own path and do their own thing.”

This narrative flattening extends to the structure as well. The musical performances in the first half are exciting moments on their own, but are held together by a directionless plot. It is composed nearly exclusively of “Bob Dylan sings a song and the crowd is in awe,” as if nudging the geriatric viewers sitting next to me and saying: “This was you back then, remember? You loved Bob Dylan, right?”

Visually and stylistically, Mangold operates as Mangold does; he is a very reliable director that can put together evocative images (e.g., in Logan, Walk the Line, Ford v Ferrari), but his compositions rarely aim to astonish or push boundaries. A Complete Unknown starts off a bit too slow but then flows with a buzzing pace in the second half, purely by the momentum of brilliant musical performances. It looks great, with a soft, warm vintage feel overlaid atop everything, and it is very well put together. However, New York City doesn’t have the grit (or drugs) that define it in favor of a tidier, more theatrical look. Dylan’s story calls for a director who shares his restless tendencies that Mangold does not have in his direction.

Perhaps the wisest choice in A Complete Unknown is, as suggested by the title, to refuse to psychoanalyze Dylan. Mangold resists the temptation to inspect his inner workings and explain his motivations, showing that Dylan is, and always will be, a mystery. But this restraint also highlights the film’s larger problem: It doesn’t have much to say. For a figure as transformative as Dylan, A Complete Unknown leaves you wishing for a bolder, more daring film.