It’s a random Wednesday in the middle of the semester, and you’ve just woken up to an alarm you set almost a month ago. You furiously type in your login information and pull up time.gov on a separate window. Some of your friends are even using two or three different devices just in case one decides to self-destruct at the eleventh hour or leaving their house to find a “place with better wifi.” You have a Plan A, Plan B, Plan C and a (hopefully untouched) Plan D. It is a free-for-all; it is a bloodbath. To Hopkins students, it probably sounds like I’m describing that fateful day known as class registration. But I am, in fact, describing something else entirely: the arena of concert ticket online sales.

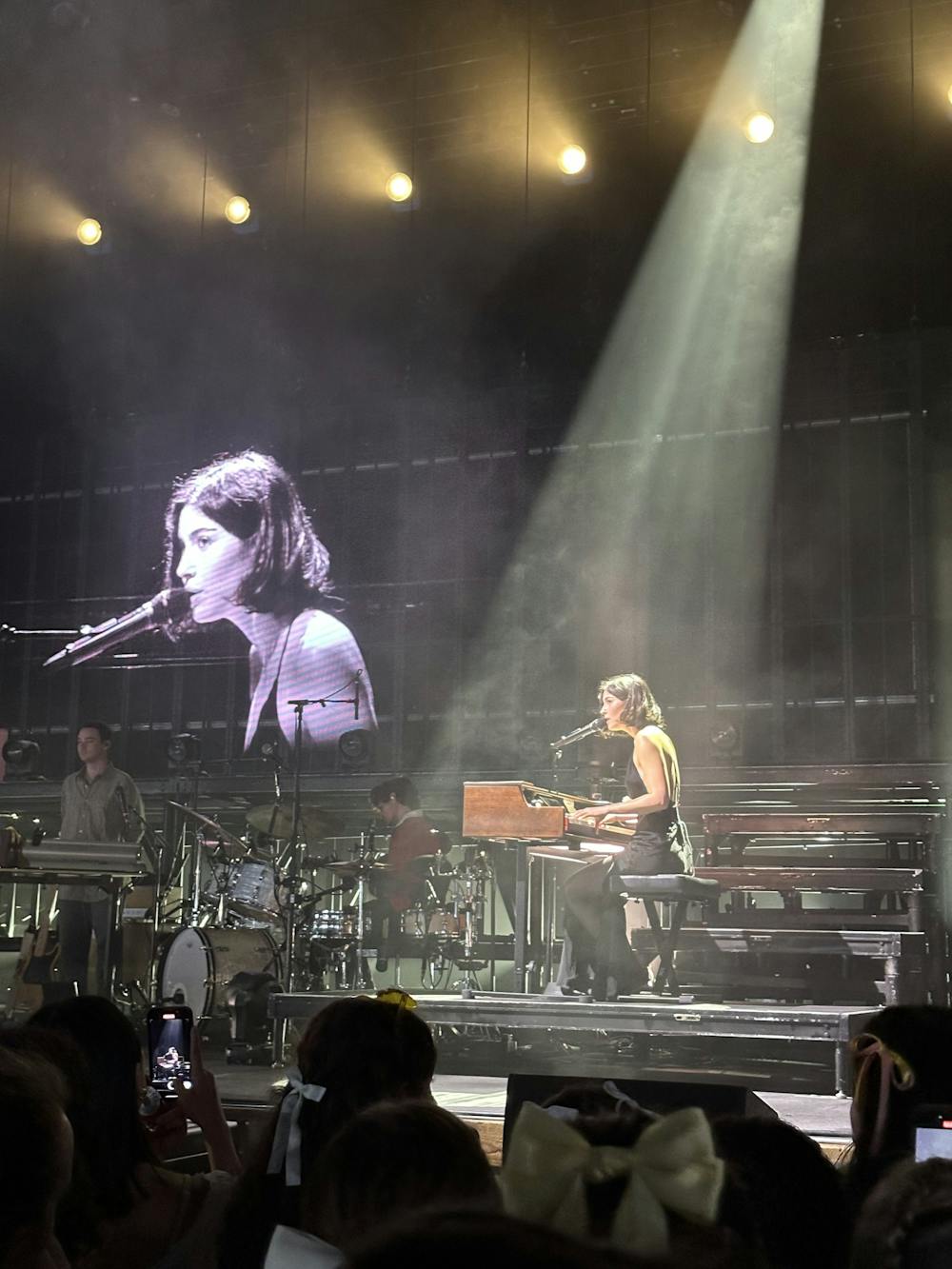

It wouldn’t be music without a live performance. Watching an artist actually step out on stage after months of waiting, hearing fans all around you sing along to the same songs you’ve listened to and feeling the effects of music fill the air — it’s the heart of music. But live music has started to become less and less financially accessible. Taylor Swift has performed over 150 shows on The Eras Tour over its lifespan of nearly two years, selling out stadium after stadium. As an artist with over 90 million monthly listeners on Spotify, it doesn’t come as a surprise that scoring tickets to one of Swift’s shows is quite the competition. Yet, this doesn’t come without a hefty price tag, with some facing resell markups up to $2,000 — not to mention the cost of travel, lodging, merchandise and other essentials of the concert experience.

The increasingly virtual nature of ticket sales means that fans often have to resort to buying tickets from online ticket scalpers if their laptops don’t load in time, and none of the markup actually goes to the artist or venue. Concert culture itself has become more cutthroat, with camping out at 8 a.m. to rush through doors opening no earlier than 5:30 p.m. becoming commonplace for general admission audiences. Instead of an exciting evening, concerts are becoming a physically taxing and draining event that takes up an entire day if you want a good seat — if you can even afford it.

Music culture is dying. From this extremely difficult — not to mention often immensely expensive — process of buying concert tickets to the disappearance of intricate melodies, the music industry is facing one of its greatest threats: the collective loss of integrity.

Music has historically held a significant role in social and political movements, with musical experimentation driving the American counterculture of the 1960s and the nueva canción of Latin America’s struggle for justice from the 1950s to 1990s. Musicians, as artists, have powerful voices that reflect that of the people, and music’s ability to deeply resonate with its listeners prove music to be a powerful tool of collective expression and political dissent that is conducive to an empowered society. Modern, extensive commercialization of music does absolutely nothing to foster this culture, as songs and albums face shortening shelf lives that have no choice but to correspond with the cycle of never-ending social media trends. Instead of a timeless and organic statement that survives years, decades or even generations of social change, the modern “industry plants” are lucky to see it past a few months on the charts.

Anyone who deems themself an “artist” has an obligation to use their platform for their audience. Art is not work done solely for the validation of the individual. Art is selfless; its naked core should not be a desire for profit or fame. Keith Haring’s story behind his established “pop art” iconography embodies what it means to be an artist with — not “above” or separate from — an audience. In Haring’s words, “The public needs art, and it is the responsibility of a ‘self-proclaimed artist’ to realise the public needs art, and not to make bourgeois art for a few and ignore the masses.” Regardless of whether or not it’s a singer, painter, dancer or writer, the identity of “artist” calls for more than just pushing out polished works; it calls for personal truth to one’s work that invites the public to take part in its distinct creation and spread.

Our right to a democratic system and freedom of expression — although an expectation — is never guaranteed, especially in the climate of current politics. Political polarization is occurring at much higher rates in the U.S. than in other democracies, a legacy very likely to be crystallized in the coming presidential term. Public opinion faces the perils of misinformation and the coming death of journalistic integrity. If musicians are beginning to step away from their roles as prominent public figures with sizable social power, this writer fears that a restrictive — if not flat out authoritarian — government is on the horizon.

Art is a manifestation of the human experience, which is by no means a stranger to resistance. We must not let the music industry evolve into a myriad of cash grabs and nepotism baby one-hit wonders, where the courage to speak one’s mind aside from promoting brand deals stands to become a thing of the past. As concert culture evolves into a kind of status symbol and albums without much replay value are pumped out faster into the market, we are losing what it really means to be an artist: being a medium of change willing to challenge the status quo.

Ayden Min is a sophomore from Los Angeles, Calif. majoring in International Studies. She is a Copy Editor for The News-Letter.