As the leaves continue to change color, scientific research similarly advances with new progress and innovation. Here are some of the recent studies in the fields of biotechnology, health and chemistry.

Mapping the human spliceosome

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona recently authored a study published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Science, which reports analyses regarding the components and functions of the spliceosome.

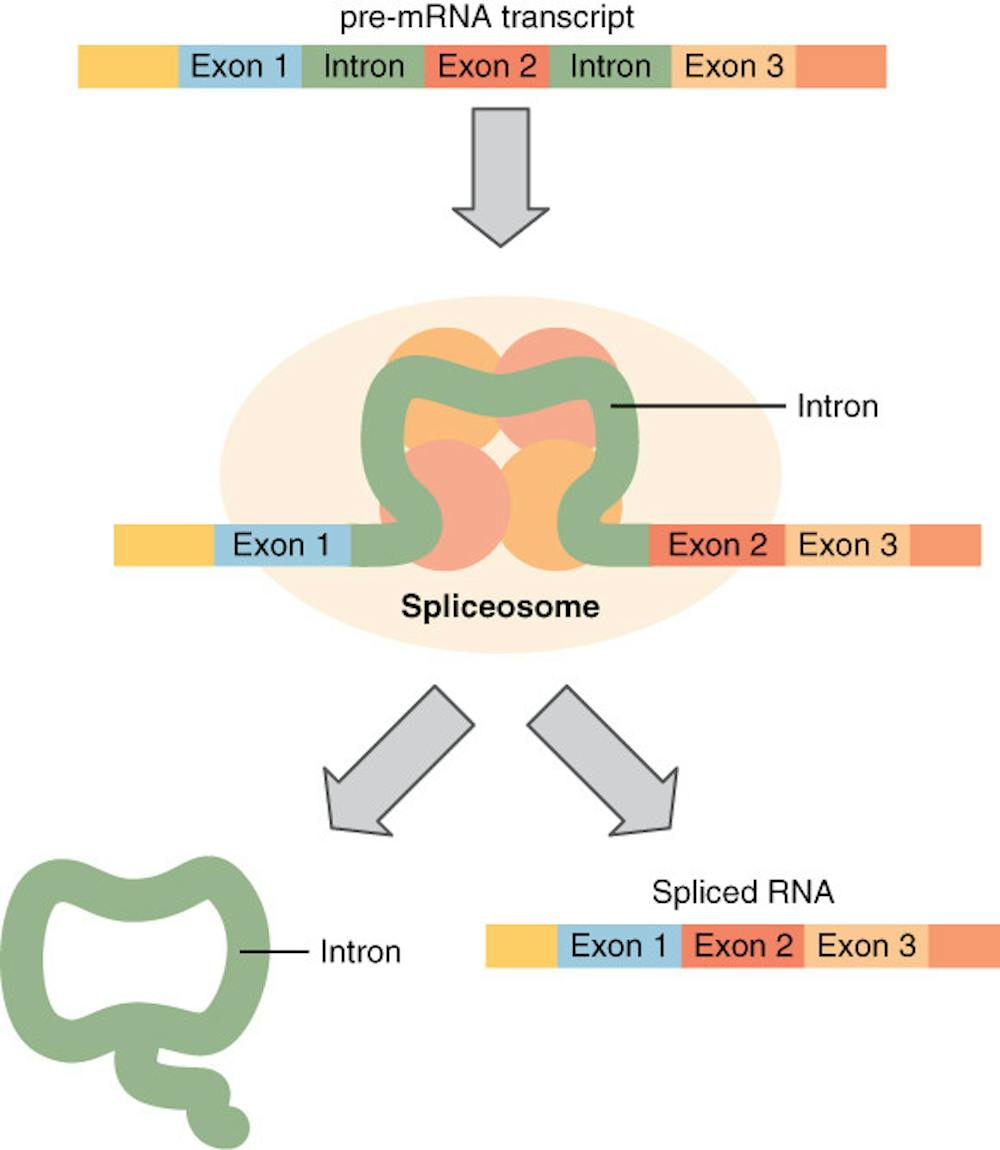

The process of creating proteins from DNA instructions begins with the formation of pre-mRNA, using DNA as a template. This pre-mRNA strand undergoes splicing where non-coding sequences of mRNA called introns are removed by the spliceosome — a large RNA-protein complex — while the coding sequences called exons are joined together. The resulting strand is called mature mRNA, which is then ready for translation, the process of protein synthesis. In this study, the authors individually knocked down (decreased the expression of individual genes) more than 300 genes involved with the formation of spliceosome components.

“The results disentangle intricate circuits of splicing factor cross-regulation,” the study stated. The authors assess the outcomes in the abstract, emphasizing how the study sheds light on a better understanding of the spliceosome and its regulation.

These findings hold promise for cancer research, as cancer cells exhibit differences in splicing mechanisms and regulation. They also have potential implications for genetic disorders like muscular dystrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which are linked to defective RNA splicing as well.

Increased sugar intake in the first two years of life leads to higher risk for diabetes

While a positive correlation between excessive sugar consumption and risk for diabetes has been highlighted in previous literature, a recent study published in Science has emphasized the importance of the first 1000 days of an individual’s life regarding their health, utilizing the historical event of United Kingdom’s decision to end sugar rationing in 1953 which naturally created a group that were exposed to lower levels of sugar consumption as well as a group made up of individuals who grew up post-sugar rationing. Individuals who consumed rationed sugar levels were within the recommended sugar intake, while people post-rationing consumed around double of previous levels. The UK Biobank was used to collect data on rates of diabetes and hypertension.

The study found that diabetes and hypertension risk decreased by 35% and 20%, respectively. Diabetes onset was delayed by 4 years, while hypertension onset was delayed by 2 years. The study also found that restricted sugar consumption in utero also decreased risk for these diseases.

Children are exposed to excessive sugar intake early on, from infant formula and breastfeeding as well as sugary foods and drinks. This study suggests that this may influence a preference for sweet foods, highlighting potential lifestyle implications, and that adhering to the World Health Organization's sugar guidelines could promote better physical health.

Kupffer cells’ role relating to meningitis for newborns

Newborns have significantly different immune systems compared to older children and adults, leading to an increase in bloodstream infections that can eventually lead to meningitis. A study published in Science Immunology detailed the role of Kupffer cells regarding bloodstream infections in newborns.

Kupffer cells are resident macrophages in the liver, playing an essential role in the liver’s functions which include acting as immune cells that fight against bloodstream infections like Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Group B Streptococcus (GBS). This study examined Kupffer cells in newborn and adult mice infected with E. coli. The researchers found that the capture rate of E. coli by Kupffer cells was 60% lower in newborns compared to adults. Additionally, 65% of adult Kupffer cells captured multiple bacteria, whereas only 15% of newborn Kupffer cells did the same. All infected newborn mice died within the first 24 hours, while all uninfected newborns and infected adult mice survived.

The study also reported that newborns and adults had Kupffer cells in different locations. Adults had Kupffer cells located in sinusoids, a specific blood vessel in the liver, while newborns’ Kupffer cells were located outside the sinusoids in the liver parenchyma, or the tissue of the liver. The Kupffer cells migrated to the sinusoids as the newborn mice grew older. Because the Kupffer cells are now located near the bloodstream, the immune system strengthens to combat potential infections, a potential reason why the fatality rate decreases from newborns to adults. Furthermore, the migration was found to be dependent on macrophage migration inhibitory factor, its receptor and the protein CD44.