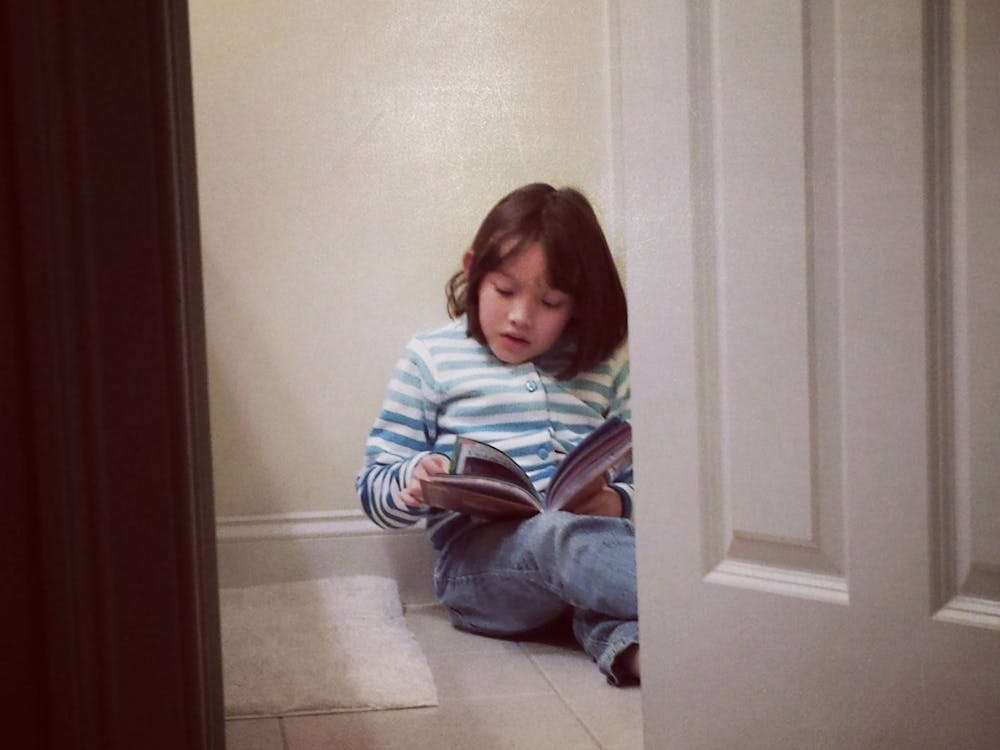

I’ll never forget the moment I saw “You’re Admitted” flash across my screen. I was sitting criss-cross applesauce on my bedroom floor, working on an AP European History project when I received an email notification saying there was an update to my portal. I set my phone up to capture my reaction. I tried to tame my excitement by muttering, “Who cares if I get into Johns Hopkins,” but inside, I craved the validation of an acceptance. As the screen lagged, my anxiety built and I covered my computer, shielding myself from the possibility of rejection. Finally, the page loaded, and there it was: a banner of acceptance. I laughed, clapped and immediately shared the news with my family.

I didn’t know it then, but that acceptance would mark the beginning of a journey that challenged what I thought I knew about access and belonging. Hopkins wasn’t my dream school; it was just one of the many schools that I simply decided to “shoot my shot at” like many other students, just hoping for acceptance letters and maybe even academic validation. This moment felt significant as I looked back to the culmination of years of hard work. Yet, as I began my journey here, I quickly realized that my place at this university — our place as underrepresented students — is not as secure as a simple acceptance.

Not once during my application process did I imagine that I was accepted because of my race, ethnicity or First-Generation, Limited-Income (FLI) status. In fact, I feared these aspects of my identity would hinder my chances. Identifying as FLI often felt like a scarlet letter rather than a badge of honor. I worried I would be overlooked because I didn’t fit a certain mold or because my parents couldn’t afford the education I dreamed of.

I worked tirelessly to bridge those gaps, crafting a high school experience that mirrored the resources I thought my peers might have. Throughout my entire life, I loved to dance. My family could never afford to put me in a dance company or a professional studio, but that did not stop me from going to YouTube every day and learning different ballet techniques, putting on dance videos to follow them along and watching tutorials for specific skills. I did paid research programs during my high school summers, and my parents worked out a payment plan with my school so I could finally be on a competitive dance team. They weren’t the parents who could attend every competition — they were working so that I could make it to every single competition. I learned my work ethic and resilience from them.

This sense of striving didn’t disappear when I arrived at Hopkins; it only intensified. I was grateful for the opportunity, but I was acutely aware of the effort it took to “fit” into this space. As I settled in, I met peers with similar backgrounds, each of us fighting to establish a sense of belonging. We didn’t just work hard in our studies; we worked hard to navigate a system that wasn’t built for us. Affirmative action, I came to realize, was never meant solely for students of African American descent, but it has come to represent a lifeline for many underrepresented students. For us, affirmative action isn’t a free pass — it’s assurance that we have a chance in a process often rigged against us.

From personal experience and working with the Baltimore community, I’ve learned that the unique experiences of Black and brown individuals in America often can’t be separated from sociodemographic and socioeconomic realities. The struggles we face are woven into the fabric of our lives. It’s challenging to conduct a truly “holistic review” without acknowledging the context that race and ethnicity provide. Our backgrounds don’t define our potential, but they reveal the resilience it took to reach this point.

Many of us at Hopkins aspire to continue our education beyond undergrad, but the barriers we face did not end with our acceptances to the University. I have often felt a need to prove my intelligence in class before a sense of collaboration emerges with my peers who don’t look like me. There have been campus events and socials where I felt anything but welcomed, and that feeling fades only in spaces carved out for Black students. In my freshman year, I remember making just a few genuine friends. The rest of my interactions felt stilted, as though I was trying to fit into the Hopkins mold, leaving little room for my authentic self. I held back from playing the music I grew up with, from dancing and speaking in ways that felt natural. I shrank parts of myself to blend in, hiding pieces that made me, me.

As underrepresented students, we see a campus that claims diversity as a value but struggles to uphold it in practice. When Black faculty and staff openly question the security of their roles, when programs like Johns Hopkins Underserved in the Medical Professions (JUMP) expand their mission to go beyond “underrepresented” students in medicine, we see that. When the turnover of Black staff feels alarmingly high and leaders of Black and African diaspora student groups worry about their clubs’ future, we see that. When SGA delayed their statement addressing the drop in Black and brown students in the Class of 2028, we see that too. Each of these moments chips away at the foundation of the community we thought we could build here.

I feel a growing sense of loss, as though our “home” on this campus is slipping away. We’re losing spaces where we can gather safely, losing each other and hope as the number of underrepresented students drops and our voices go unheard. I fear for the future — if the trend of fewer matriculated black and brown students continues, what will Hopkins look like for them? Will they have to navigate an even lonelier, more isolating path?

Kyarie Shelton is a senior from Indianapolis, Ind. studying Natural Sciences and Psychology.