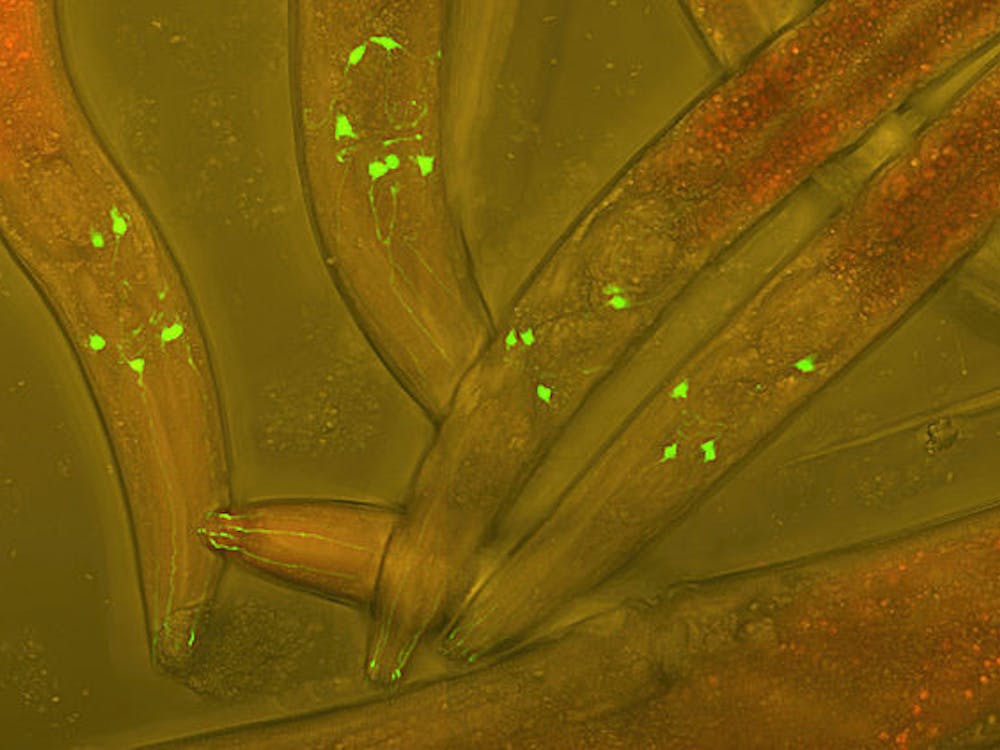

A chimera is an organism composed of cells from two or more distinct genotypes. Human-animal chimeras are a budding area of research and involve the introduction and growth of human tissues in an animal. Chimerism research holds great promise in improving the availability of organs for organ transplantation, which is a major issue due to the current severe organ shortage. Initial chimerism studies involved smaller organisms, such as one where researchers attempted to grow a rat pancreas in a mouse.

Building on the success of these results, researchers believe that such experiments could potentially be used to produce human organs, as well. Pioneering experiments have been conducted in various fields of organ xenotransplantation, from cardiology to nephrology: In 2022 and 2023, two experiments successfully transplanted genetically modified pig hearts into humans, demonstrating the potential for longer-term survival and functionality. There has also been some research demonstrating that genetically modified pig kidneys can function in nonhuman primates for extended periods.

However, xenotransplantation is also perhaps the most ethically gray area of chimerism research. As the field shifts to larger-scale studies, it is important to discuss limitations and ethical considerations when approaching such studies. Many critical stakeholders — including animal rights activists, ethicists, and governmental and regulatory bodies — could find it difficult to support chimeric research due to its adverse implications for nonhuman animals and the safety concerns it poses.

Firstly, it is essential to address concerns associated with animal testing as a whole. The insertion and development of human stem cells in nonhuman animals can result in unexpected harms. To that end, two major conclusions can be made: First, regulatory bodies should ensure that the welfare of nonhuman animals is prioritized throughout chimeric studies. Researchers interested in conducting chimeric research must provide a rigorous justification for the use of nonhuman animals and clearly outline how they will adhere to safety standards while ensuring the quality of life for these subjects throughout the study. One example of such a policy is regularly performing a systematic analysis of vital signs and behavioral cues in nonhuman animals throughout the course of a chimeric study.

A second area of consideration for xenotransplantation stems from public opinion, as many are opposed to chimeric research. Because some research uses human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) that involve embryonic destruction, many individuals have moral qualms with using wet-lab techniques that are related to hESCs.

Xenotransplantation also raises the question of human consciousness. Specifically, human-animal chimeric research related to the growth of human brain cells in animals can result in heightened cognition in nonhuman animals. This side effect that begs the question, “How human is too human?” for a nonhuman animal. Is it still ethical to perform research on a nonhuman animal if it has elements of human cognition? This is a critical question that researchers must be able to adequately answer to justify the continued pursuit of chimerism research.

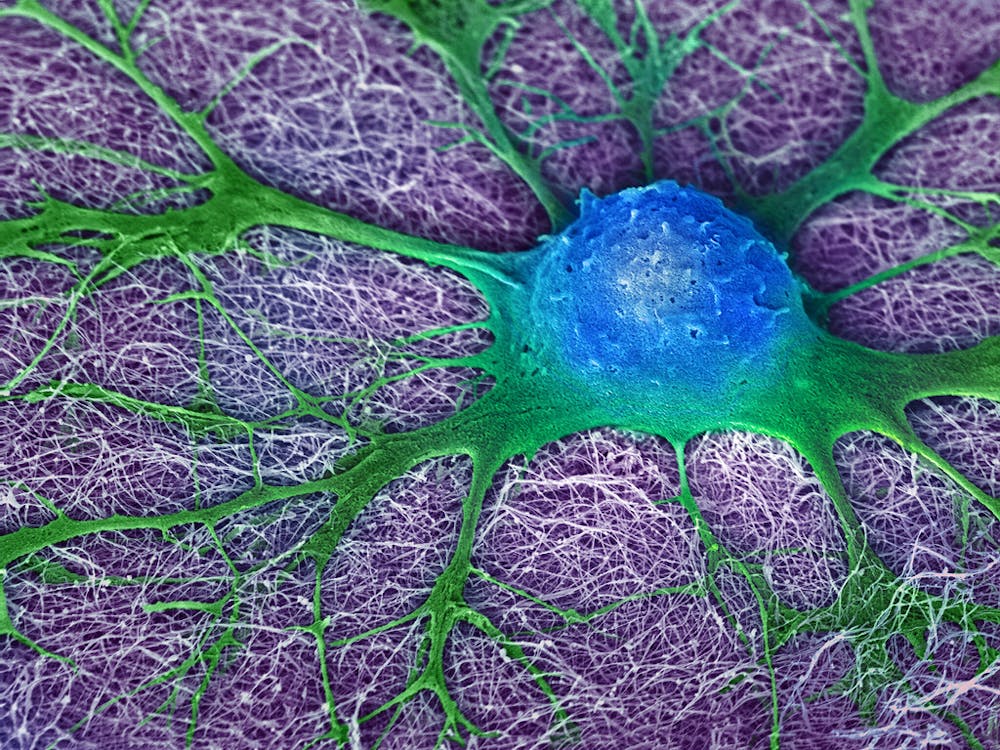

An early study in human-animal chimeras injected human glial progenitors into immunodeficient mice; at the end of the study, it was found that a majority of the white matter in mouse brains was human in origin, indicating that it could be possible to impart consciousness or cognition to nonhuman animals through xenotransplantation.

However, risks concerning human cognition are difficult to predict because chimeric research is still in its early stages. It is difficult to understand the moral implications of changes in cognitive ability — particularly of those that affect awareness or autonomy in nonhuman animals — and there is no clear consensus on the regulation of this type of research. Consequently, the only policy recommendation at this stage is that there should be some sort of regularly-convened, national regulatory body to consistently update regulations in chimeric research. In all, the benefits of human-animal chimeras warrant continued effort in this field, but regulation needs to keep pace with innovation to adequately address ethical and logistical concerns with the growth of human organs in nonhuman animals.