Cleaning the bathroom is usually an annoying, insignificant task. Wim Wenders’ latest film, Perfect Days, takes this chore and transforms it into a vessel for gratitude. The film follows a series of days in the life of a Japanese bathroom cleaner, Hirayama, in minute detail. His everyday routine is monotonous and, on the surface, decently bleak. But despite a premise that is fairly uncompelling on the surface, Perfect Days is a moving depiction of finding meaning in the mundane.

The film’s protagonist, Hirayama (Koji Yakusho), is a middle-aged man who spends most of his day cleaning public toilets throughout Tokyo. He carries out his custodial job with the utmost care and respect, even if it doesn’t seem to warrant it. Much to the dismay of his only coworker, a younger man named Takashi, Hirayama cleans every toilet with great diligence. Takashi laments that everything they clean will just get dirty again anyway, but Hirayama takes pride in making sure he leaves every bathroom spotless.

In addition to having a passion for his job, Hirayama also finds happiness in other facets of his life. Most of his day is spent going from bathroom to bathroom, but he seizes any free time he has to also carry out his other hobbies, such as botany, music, literature and photography. He wakes up at the same time every morning to water his plants. Before every drive to work, he carefully selects a cassette tape from his collection to listen to; he has his lunch break at a park, where he takes photos of the scenery around him; and, every night, he reads before going to sleep.

Hirayama lives a solitary life, and for the first hour of the film, there is barely any dialogue. He makes the necessary remarks to his coworkers, and he answers the occasional question from people using the restroom. He is content with receiving the same greeting from the waiter he sees every afternoon, and he is amused by the daily gossip he gets from the owner of the restaurant that he goes to in the evenings.

Because of his solitude, these minuscule interactions that he has with others are more profound. However, there is a twinge of uncertainty lurking beneath his routine. He’s getting by with what he has, but Hirayama’s meticulously arranged life can be easily upturned with a single disruption.

When his niece, Niko, runs away from her home, Hirayama finds her waiting outside his home announced. Niko accompanies him to work, and she takes pleasure in following Hirayama’s routine, even watering his plants for him and picking a book from Hirayama’s collection to read at the end of the day. Initially, Hirayama displays no difference in emotion with her than he had shown without her presence. He was perfectly satisfied with his life before, and during her time spent there with him, he’s still just as fulfilled.

What rips through his normal demeanor is Niko’s departure. When his estranged, wealthy sister arrives in a chauffeured car to pick up her daughter, a bit of Hirayama’s past is revealed. His sister begs him to visit their ill father, who is staying in a nursing home, and she worries about his occupation, expressing her confusion as to why her brother is cleaning toilets for a living. Hirayama refuses her requests and questions, but he hugs her before she leaves with Niko. As they depart, Hirayama breaks down in tears.

The rest of the film continues in the same manner as the beginning. Hirayama’s days are depicted without much change, from the moment he wakes up to the moment he closes his eyes again for a night’s sleep. There are a few more events that continue to disrupt the rhythm of his life, but the time when he connects with, and subsequently parts from, his niece is the most major disturbance in Hirayama’s way of life.

Regardless of these changes, the film ends in the same way that Hirayama’s work days all start: in his car, with music playing in the background. In defiance of everything that has shaken up his ordinary life, Hirayama returns to what he knows best.

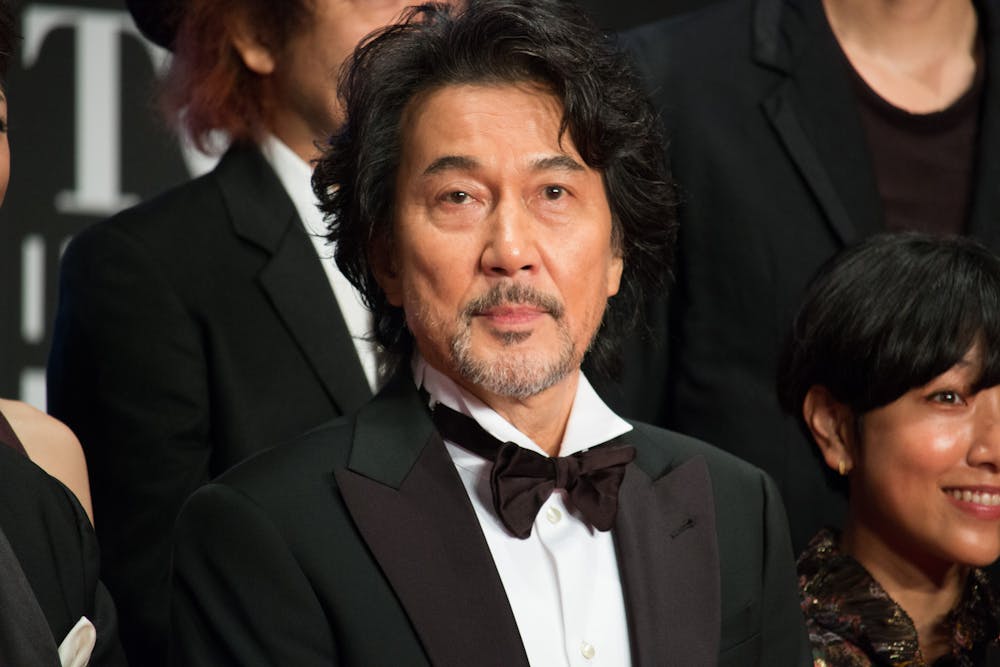

Yakusho delivers a subtle, but tender performance as Hirayama, a man getting by with what he’s got. His role earned him the Best Actor Award at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, and the film is in contention for this year’s Best International Film at the 2024 Oscars.

The film’s greatest strength is its direction. Wenders opted to shoot the film in an intimate 4-to-3 ratio, creating a boxy viewing experience that allows the viewer a close look into Hirayama’s life. Most impressively, the film doesn’t shy away from depicting every part of Hirayama’s days, even moments that would be glossed over by other auteurs not as devoted to a niche of repetition as Wenders is. For example, Hirayama’s visits to the bookstore are well-documented, from deciding what book to read next to making small talk with the cashier about it. His process of developing the photos from his film camera is shown in its entirety, even up to the moment when he tosses out badly captured photos.

For the less patient viewer, this may be seen as a flaw. Perfect Days has a runtime of over two hours, and for the average person, a chunk of it would seem repetitive. Even though I have no preference for a film’s length, I would recommend this to a wider audience if it had been half an hour shorter.

Perfect Days has a misleading title. Hirayama’s days aren’t perfect by definition. There are days when he’s faced with a past he’d rather not confront, when he has to throw away more photos than he’d like or when he’s left with only his shadow for company. Still, he doesn’t worry about what the next day might bring. Hirayama knows that his simple days will return, and as long as he appreciates the mundane things that surround him — taking inventory of everything that brings him the smallest bit of joy — he will always find peace once again.