Tucked into the Baltimore arts district is a gallery called the Maryland Art Place. You come to it, like so many places in this city, through streets of row houses and alleyways, smoke shops and convenience stores. Then all of a sudden you are there, looking into its big glass windows with “MAP” written on them. Inside it is warmly lit, densely populated with conversation and artwork.

This time, it was all about bodies. On Jan. 25, Maryland Art Place (MAP) held their opening reception for the show Embodiment, an exhibition meant to say as much as possible about the human form: what it is like to have one, how it looks, how it doesn’t look and how you move about the world. Besides depicting the body, though, there was not much else tying all the artwork together. Mediums ranged from ink to bronze, tapestry to papier-mâché. Textures, too, varied greatly. Certain pieces were engorged and bumpy; others were slick and shiny. Some depictions were perfectly realistic, even photographic. In an interview with The News-Letter, curator and exhibit director Caitlin Gill spoke about this intentional diversity.

“One of the goals was definitely to represent a lot of different types of bodies, as well as a lot of different stages of the body,” she said. “[I wanted] to have representation from infancy to the elderly — people who are working with disability, people who are working from female and male spaces. And with the whole variety of mediums too, [I hoped that] there was something for every type of exploration.”

Walking through the gallery, you lurch from one experience of the body to the next. Some of them will feel familiar, especially if you are a woman — after the show, my friend turned to me and remarked that almost all of the bodies depicted were female bodies. Others, dealing in affairs like ethnic expression and pregnancy, may feel like entirely foreign representations. While I cannot describe the experience of each of these artworks — you will have to go and see for yourself — here are a few pieces highlighted along with statements from their artists.

COURTESY OF NOËL DA

Photograph of Origin of the Family, by Joan Cox. Oil on Canvas, 96” by 54”.

This is the piece you first see when walking into the show, immediately greeted by rich color and texture. Having been primed to study the body, the first thing I noticed was the swirling stomach of the pregnant woman. It seemed like the only part of the painting to have a distinct motion to it. A week later, I was able to ask the artist about why she painted the stomach like this in the middle of the painting. In an interview with The News-Letter, Joan Cox talked about the unconventional nature of this feature.

“If you study composition, they tell you not to put anything important right in the center, because then everyone just zooms right there. But that’s exactly what I did. I like to put a thousand colors and swirls because I want you to get lost in it. Like she’s holding the universe and the future of the world right there,” she explained.

Our conversation moved leftwards, towards the androgynous figure sitting next to the pregnant woman. Cox told me about how she chooses couples to photograph for painting reference and the choices she made with this portrait in particular.

“Visually, the movement is very strong. So, you might be grabbed at first by the belly, and focus on that, but your eye is still going to go over to the left and examine her face a little bit. [You’ll ask,] ‘Is this a female face? Is this a trans face?’ And it’s very purposeful, who she is. I chose her very purposefully to represent that gender-neutral person and for her to come forward and support her partner. It’s a family,“ she said.

Another androgynous depiction at the show came from a piece by Richard Lopez (RLo) Hernandez, an artist based in Harrisburg, Pa.

COURTESY OF NOËL DA

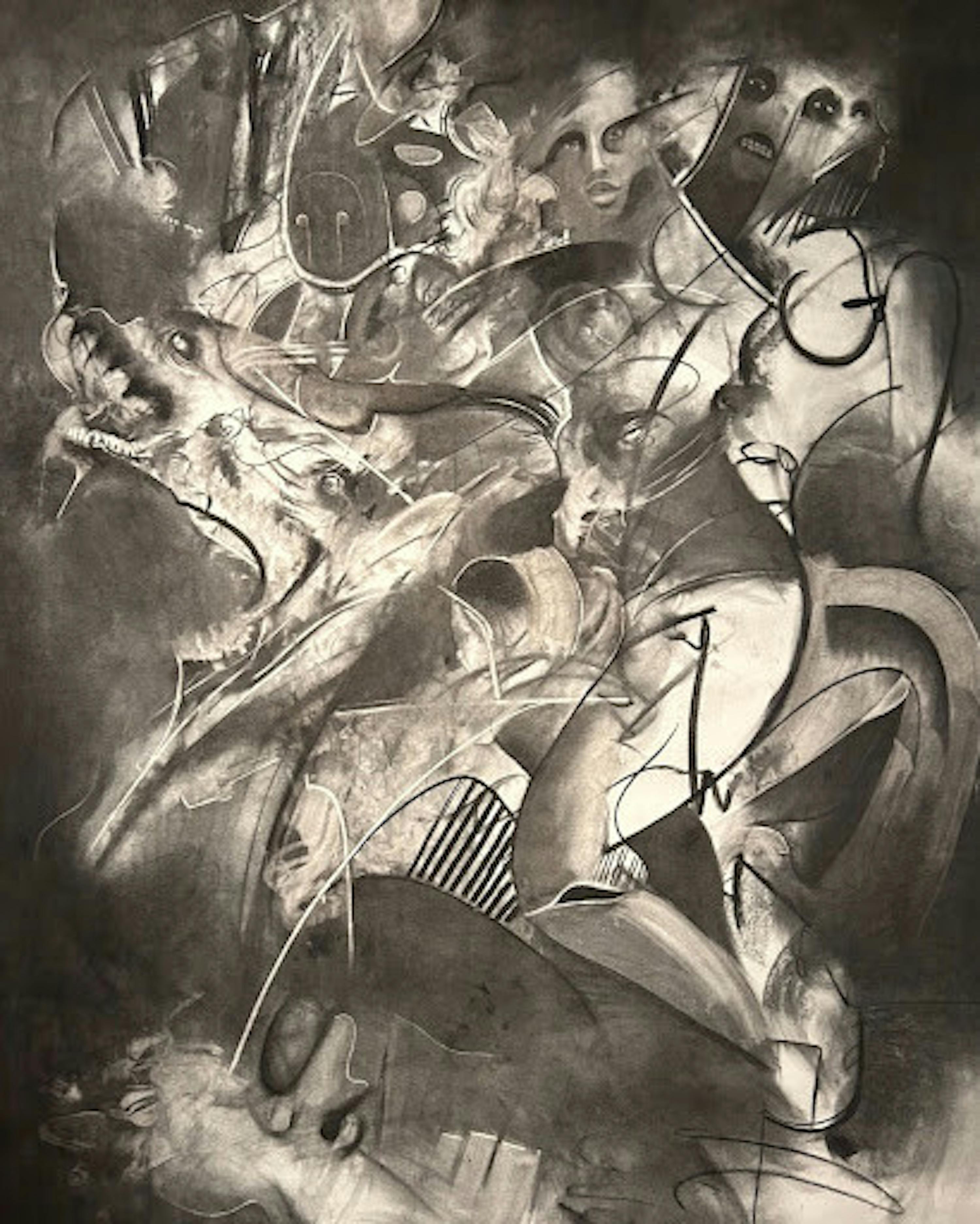

Detail from Untitled, by Richard Lopez Hernandez. Charcoal on unstretched canvas, 67” by 53”.

This piece was deeper into the exhibit, in a corner with a platform. It was quite large, and because of how small the platform was, you have to stand quite close to it. You are really only looking at the detail before you can step back and look at the piece as a whole. I was standing next to two visitors, listening to them talk as they realized in real time that there were faces and figures embedded into the strokes. In an interview with The News-Letter, Hernandez spoke on these figures.

“I like to have a lot of androgynous characters. I like the idea that I can’t tell who or what they are, I just want to let them live as they are,” he expressed. “However I describe or suggest them in that moment is how they will be consumed, but for the most part I like to play around with a lot of androgynous characters.”

Our conversation continued into topics of artistic process and expression. Hernandez told me about how he works layer by layer, pushing and pulling the charcoal on the canvas.

“Instead of using either an additive or subtractive process, I do both at the same time.”

COURTESY OF NOËL DA

Photograph of Ultrasound, by Evan Boggess. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 60” by 48”.

Incidentally, this piece, like Origin of the Family, is also a depiction of a pregnant woman, but its focus was different. If you see the paintings in person, you can feel this shift. They are hanging very close to each other, and you can sense how the two differ as you walk by: One is joyous, while the other has a colder gloss to it. In an interview with The News-Letter, Evan Boggess described the context of the portrait:

“That’s actually a portrait of my wife,” he revealed. “We were waiting to have our second child [...] and we got to be really familiar with the insides of medical waiting rooms. [...] It didn’t really imprint on me at that time, but looking back on it, there are certain things that I just can’t stand now.”

Boggess then went on to discuss one of his favorite examples:

“Fake silk plants, for instance. [...] They’re just so perfect and pristine, but they’re also dusty and nasty and bleached out from the sun. And then there’s the books and the tile — all the things that you would normally just dismiss, but there’s something about the tension of waiting to hear back about something as monumental as [a child]... And so in that [piece], I was trying to build up that feeling of extreme tension, excitement and revulsion,” he explained.

These were just some of the artworks on display at the Embodiment show, which is open until March 23. It is the product of many months of work and careful curation, painting and planning. I recommend you go see it, especially if you have a body.

Editor’s Note: This article was updated to correct the medium of an artwork and include an artist name. The News-Letter regrets this error.