How do you encapsulate the entirety of an extraordinary life in 2 hours and 11 minutes of film? You do it in the way any person does when they are old and alone at the end of their lives. By sitting back and letting memories, both treasured and painful, flit before your eyes in a frenetic montage of important moments.

Maestro is a biographical film written and directed by Bradley Cooper which tells the story of the marriage of Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre. The movie has largely flown under the radar, overshadowed in the awards season by heavy hitters like competing biographical movie Oppenheimer, but I found it to be a stunning and tender depiction of a life shared between two great artists in a complicated situation.

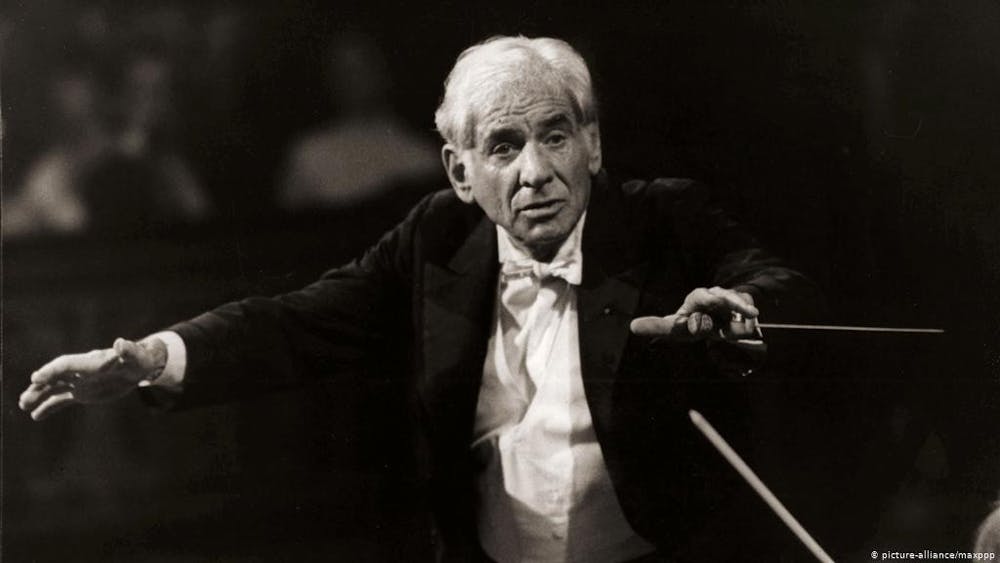

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) was a composer, conductor, pianist and educator who lived from 1918 to 1990. Dubbed “the first great American conductor,” he was famous for his illustrious conducting career, for creating the televised Young People’s Concerts series and for composing the music to West Side Story.

Felicia Montealegre Bernstein (Carey Mulligan) was a Costa Rican-Chilean actress and activist who lived from 1922 to 1978. She performed on Broadway and on television in productions such as Joan of Arc at the Stake and A Doll’s House.

As I was looking up information on Montealegre for this article, it was almost impossible to find information on her which didn’t prominently mention Bernstein as well. There lies one of the core conflicts of the movie and their marriage. As Bernstein grew and continued in his career, her own career and life became increasingly overshadowed by his fame. She was a strong artist and activist in her own right, and yet so much of her legacy is defined by her role as a wife.

As the film begins, before seeing anything, we hear a piano being played. The piece is lonely, dissonant and quietly reflective. An aged Bernstein sits at the piano, playing “Act I: Postlude” from his opera “A Quiet Place.” He admits to the silently watching camera crew that he sees his dead wife in the garden from time to time and that he misses her terribly.

And from there we jump back to the past, signposted by the switch to black and white. A 25-year-old Bernstein, wild with youth and talent, is being told that conductor Bruno Walter is ill, and he’ll be taking over for him as conductor of the New York Philharmonic that evening. From there, he’s catapulted to massive success. He meets his future wife, Felicia, at a party, and the two absolutely sparkle with chemistry from their very first conversation.

They get married, have three children and live together for a time in New York. Bernstein flourishes in his musical career while Montealegre balances her acting career with her new duties as a mother and wife. During this time, Bernstein has romantic affairs with men, all with Montealegre’s knowledge. She clearly loves him and wants him to be happy, but the strain of keeping Bernstein’s homosexuality a secret from the world, including their children, and having to put up with his infidelity clearly weighs on them more as the years march on.

This puts pressure on the marriage, and the two separate for a time, though they eventually reconcile and hold their family together. Eventually, Montealegre is diagnosed with breast cancer and dies soon after, leaving Bernstein to grieve and move forward in a final coda of his life.

Maestro moves between scenes just as one would travel through memories. In a way, it feels like Bernstein is, at the end of his life, seeing his life with Montealegre flash before his eyes in a whirlwind of memory. Scenes transition into each other in a seamless barrage of significant moments. The early years, in black and white, glitter with flashy cinematography and nostalgia. The later years, in color, are tender and complicated, and so they feel more real and human.

The film did a wonderful job portraying the two’s relationship in a sensitive and strangely unobtrusive way. Nothing is explained explicitly to the viewer. We have to figure things out by listening to conversations and tracking changes in the tone of interactions. Many scenes in the film are shot from doorways, corners of rooms and hallways. As viewers, we are just spectators peering into their lives without fully entering them, for better or for worse.

The cinematography is stunning, especially in the black-and-white portion that takes up approximately the first third of the runtime. If you’ve ever seen old photographs of Leonard Bernstein as a young man, cigarette hanging from his lips as he focuses on whatever task, the film recreates the look exquisitely.

And even after the transition to color, it still retains the pastel quality of an old technicolor film, matching the style of recordings of Bernstein and Montealegre from the time. The whole movie feels like a collection of archival footage pulled out of some dusty box in a closet and finally brought to life.

It would be impossible to discuss the movie without mentioning the score. The presence of the music in Maestro is alive in a way I’ve never seen in any movie. The vast majority of pieces in the score come from the varied repertoire of the real Bernstein’s compositions. The sound is mixed so that the music is at the front, like what one would usually see in a music video. Life is just a background for the music, not the other way around.

The most jaw-dropping feat of the movie was the recreation of the end of Bernstein’s 1973 performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 with the London Philharmonic. It’s an uninterrupted 8-minute scene where we get to watch Bradley Cooper’s physical acting skills really get put to work. He’s fully conducting the orchestra here, which is the real London Philharmonic, and doing so not just in a technical manner but with the same unique and passionate style of the real Bernstein.

The exaggerated expressions of joy and ecstasy and pain, the wide and passionate beating of time with the baton, the little hops accenting downbeats, the gestures cueing and encouraging different sections of the orchestra and that far-off, intense look in his eyes that says he’s completely gone with the music. It’s all perfect. Some of that can be attributed to the advice of extremely overqualified conducting consultant Yannick Nézet-Séguin, but it’s clear that an extreme amount of love and labor was put into this scene.

And to cap it all off, the perfect, bittersweet ending to this 8-minute scene is the reveal of Montealegre watching from the side. On her face is an indescribable look, something between love, suffering, pride and awe. And as Bernstein walks offstage with the applause thundering around them, she ends their separation, and with relief they come together as a couple once more.

Maestro is not as dramatic or as interestingly plotted out as some of the other films nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars this year. But it is a tender, beautiful and honest portrayal of a complex marriage. It spans decades with grace and is a visual and sonic masterpiece. Even if you’re not interested in classical music or the work of Leonard Bernstein, I would highly recommend it to everyone. Bravo!