On October 7, the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) celebrated the 13th anniversary of the Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture, a symposium of lectures related to the lasting legacy of Henrietta Lacks, the ethical implications of her treatment by Hopkins and the future of clinical research.

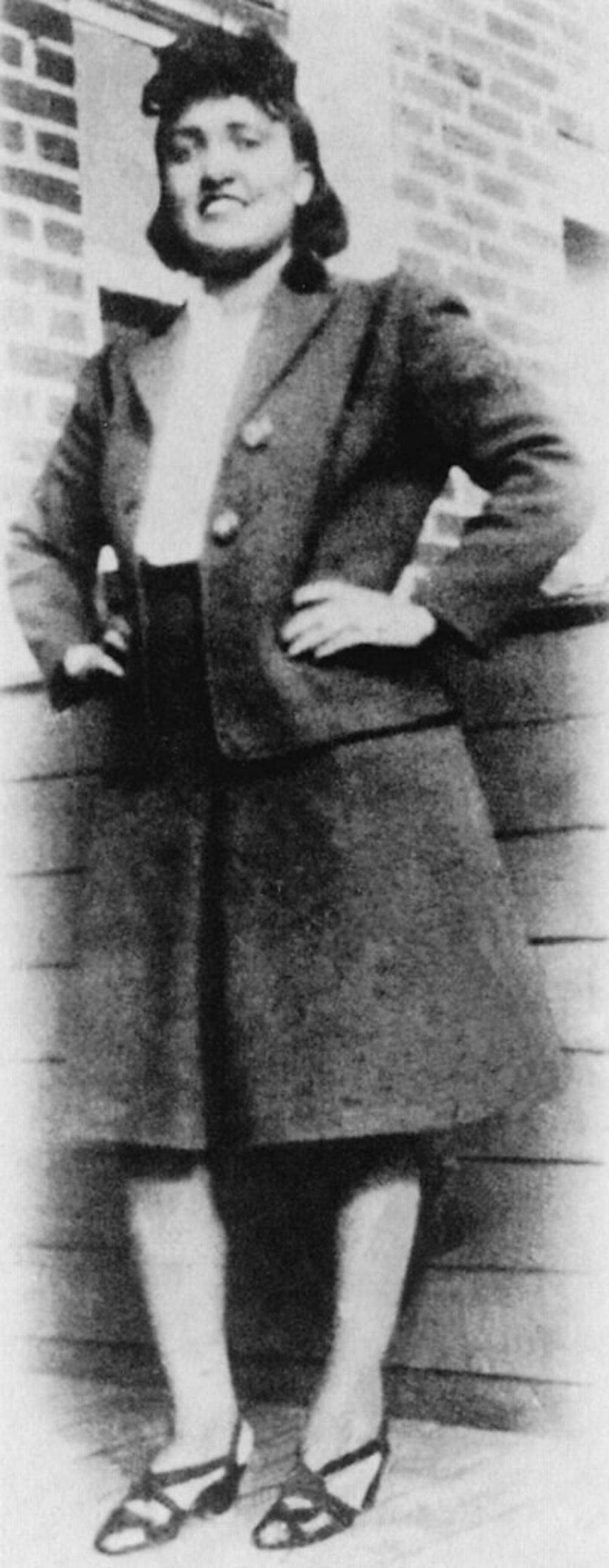

The event began with an overview of Lacks’ story, told by her great-granddaughter, Iyonna Carter. In January 1951, Lacks came to Hopkins Hospital for a lump on her cervix. She was diagnosed with stage 1 cervical cancer a few weeks later. During her first radiation treatment, her doctor took samples of her cervical tissue without her consent to see if they would grow in culture. Lacks was admitted to the hospital in August of the same year because her tumor was unresponsive to treatment. On Oct. 4, 1951, Lacks passed away. In the sample collected without consent, she left behind HeLa cells, the first immortal cell line that made possible the development of many landmark scientific discoveries in genetics and disease treatment over the past decades.

Following the event introduction, Daniel Ford, the director of the ICTR, spoke about the enduring impact of Lacks’ story and the myriad perspectives it provides on the role of clinical research in improving healthcare. The biggest takeaway from Ford’s comments was how successful clinical review practices were during the COVID-19 pandemic; despite the quick pace of vaccine and treatment rollout, few exceptions were made to expedite the clinical review process, and all of the proper procedures were followed.

“We said the system actually does work if you follow it,” Ford said. “At least at this point, we do not know of any cases where somebody was exploited in [COVID-19] clinical research ... We kept up our focus on protections.”

From a legal and practical perspective, Ford highlighted that despite the flaws and disparities in the healthcare system, the current system of clinical research resulted in vaccinations and treatments for COVID-19 with remarkable efficiency. However, the pandemic also demonstrated the limitations of science and scientific literacy in the U.S. due to the widespread disregard for scientific guidelines introduced by large public health organizations such as the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“What we did learn, though, is that not everyone trusts biomedical research,” Ford said.

Many individuals refused vaccinations and hospital treatment, emphasizing how public distrust in science, scientists and the healthcare system as a whole has magnified during the pandemic. To this end, Ford mentioned that the ICTR is introducing a new focus for the coming years to ensure they can perform better as a trustworthy research partner to the greater Baltimore community.

Public distrust in Hopkins increased after Lacks’ story came to light. From the first article published about HeLa cells in 1976, public opinion was heavily against Hopkins and its unethical action of taking the patient’s sample without consent. The University acknowledged that such practices would never occur in the 21st century without proper consent from the patient.

The University has helped create symbols to raise awareness about the life of Lacks, including a proposed design for the Lacks building on the East Baltimore campus. However, the University does not address the possible role of Lacks’ African American identity in her treatment during that time, attributing all ethics and equity concerns from her story to the lack of proper consent guidelines during the 1950s.

In August 2023, Lacks’ family settled with the technology company that had used HeLa cells for profit in the 1950s and had previously tried to get the case dimissed. The specific terms of the settlement are kept confidential.

The first keynote speaker from the event, Daniel Dawes — senior vice president of Global Health Equity and the executive director of the Institute of Global Health Equity at Meharry Medical College — delved more deeply into the broader issue of health inequity in the U.S., arguing that policy and political determinants of health are responsible for perpetuating health inequities.

“Health inequities are found in the political determinants of health, which inequitably distribute social, medical and other determinants, and they create the structural barriers to equity for population groups who lacked power and privilege,” Dawes argued during his address.

Dawes also discussed how people historically subject to segregationist and inequitable healthcare policies are more heavily affected by health inequities in the U.S. Dawes referred to historical developments of infrastructure that were seen, at the surface level, as good policies. For example, the poverty tax makes many poorer communities pay more for auto insurance and mortgages.

“Only policy can fix what policy has created,” Dawes said.

Dawes then analyzed the reason behind why certain policies were passed to either improve or hinder the eradication of health inequity.

“The political determinants of health inequities have rarely been addressed unless their reduction or elimination served other purposes,” Dawes argued. The success of policies to mitigate health inequities has depended on their palatability and relationship to commercial interests.

The second keynote speaker from the event, Dr. Lydia Pecker, the director of the Young Adult Clinic at the Johns Hopkins Sickle Cell Center for Adults, discussed the role of HeLa cells in the history of sickle cell disease (SCD) and its relationship to Hopkins.

“The first treatment for [SCD] really wouldn’t be here without [Lacks],” Pecker said.

Following the common thread of Dawes’ speech, Pecker expanded on how healthcare quality and patient outcomes for individuals with SCD are heavily affected by racism and inequity. Pecker discussed how historically segregated blood banks at most hospitals and a continued lack of basic clinical care for SCD patients reflected this reality. She pointed to the University’s renewed investment in care, diagnosis and treatment for patients with SCD, which is evidenced by the relationship between Hopkins clinicians and patients with SCD.

“There are four drugs for sickle cell disease and people cared for at ... Hopkins have participated in studies for all four of those drugs,” Pecker stated.

Wendel Patrick and Olu Butterfly performed a spoken word poem on the story and legacy of Lacks. Their rendition was followed by the final event of the memorial, which was a Q&A panel with the speakers, the performers and David Lacks, Jr., Henrietta Lacks’ grandson.

David Lacks, Jr. concluded the memorial when asked how best to honor his grandmother’s legacy.

“Let people know who she was, what her contribution was ... say her name and just promote who she was,” David Lacks, Jr. said.

Editor’s Note, 2023: The article was updated to correct the titles or names of several individuals.

The News-Letter regrets these errors.