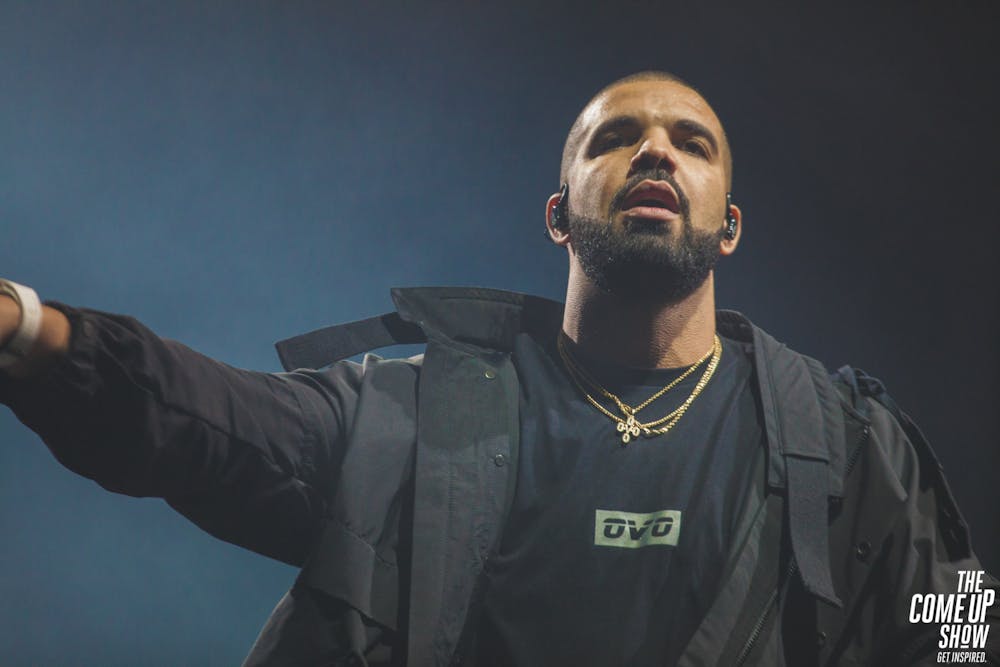

After an embarrassing venture in written poetry, with such insightful lines as, “There are two types of women in this world / women who like giving head and women who I don’t like,” Adonis’ favorite rapper and Grammy Award-winning artist Aubrey Graham (aka Drake) is back in full form.

This past Friday, Oct. 6, he released his anticipated album, For All the Dogs, which had the highest opening day streaming numbers since Her Loss, clocking in 109 million listens. For the longest time, the only thing we knew about this album was its cover art, designed by Drake’s son Adonis, and the promise (from the man himself) that this album would be a return of the “Old Drake.”

To put things lightly, he didn’t deliver on this statement; this album is far from an If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, or even a Take Care. What he should have said was “same old Drake,” because this album follows a recent tradition of his: 20+ track albums with many different sounds and zero new ideas.

We find ourselves again in the field of excess. Where are the hills and the valleys? All we can see is the endless flatness around us, an infinite plane of content — one hour and 24 minutes of content, to be exact.

It’s a common music industry tactic — push as many songs as possible into one album-shaped box so that one inevitably pops out and becomes the viral hit you envisioned. The issue is, due to the bloated tracklist, the album itself will never stand the test of time. What we have here is another Scorpion or Views, with some songs sounding like Her Loss throwaways, such as “Fear of Heights” and “Daylight,” and others tainted by the crooning, half-assed singing we all wished stayed with Honestly, Nevermind.

This isn’t to say there aren’t songs I enjoyed — mainly “What Would Pluto Do” and the distorted drum set beat of “Screw the World (Interlude)” — but isn’t this the point? I could go through every singular, specific moment I enjoyed on this album, but it would only prove the album inconsistent.

This has been Drake’s process for a while now: appeal to the greatest number of people possible so that everyone can find a song to put in their playlist. The vice of this perspective is its intention — what does it say about your confidence as an artist if you can’t commit to something first and then accept the inevitable criticism?

Following the release this past Friday, there was a general consensus on Twitter. Most people disliked the album for its lazy lyrics and its lack of a new sound. People are catching on to the negative side of long albums, and it’s getting old and tired. The recent discussion of what constitutes a “classic album” is a perfect representation of this; instead of saying everything is good, the current climate forces you to take a side. So, will For All the Dogs be considered a classic album in, say, 20 years?

While I can’t hop in a time machine and find out for myself, I can, with a high level of confidence, say that it will not. By its very nature, For All the Dogs is a curated playlist of contrasting styles and flavors with little artistic invention, and when it delivers, it does so in a way we’ve seen Drake perform before.

Let’s return to the question that recently consumed hip-hop Twitter: What makes a classic album? We’ve gotten to the point in contemporary music where it seems like multiple “classic albums” are released every year. It’s true, we won’t know what’s classic until we live through its legacy. That’s part of what classic means — an old piece of work that “shook the game up” and still remains relevant. It’s only natural for people to guess, though. Opinionated fans grow prideful in their pursuit of being the first to identify a great album and so cling to the biggest artists.

Take “IDGAF (feat. Yeat)” — is there a single element of the production on this track that we haven’t heard on a Yeat solo album? There aren’t bells, I’ll give it that, but the song is so out of place. Is Drake an executive producer? Is he DJ Khaled? If no, then why does he cater so heavily to his features? Is it a Yeat or Drake song? This same criticism could apply to “Slime You Out? (feat. SZA)” and “Amen (feat. Teezo Touchdown).” Whose album is this truly?

Now, why do I go on and on about classic albums and legacy? You might be wondering if Drake cares about all of this. Maybe he just wants to make music and have fun, maybe he doesn’t care what other people think about his art. Well, let’s see what Drake himself has to say about that.

On a recent episode of The Joe Budden Podcast, the retired rapper had a lot of choice words for Drake and his new album. His main criticism was that Drake needs to “start acting his own age.” He also went on to discuss “First Person Shooter,“ the sixth track of For All the Dogs, which had a featured verse from J. Cole; Budden maintained it completely washed out Drake’s.

All of the discussions of legacy coalesce here, mainly because of J. Cole and Drake’s status as two of the “big three” rappers: J. Cole, Drake and Kendrick Lamar. While all three have never and probably will never be on the same track, this is as close as we’ll get to having the “big three” compete over the same beat. They acknowledge this with their verses several times. Drake repeats, “Who the G.O.A.T.? Who you bitches really rootin’ for?” and J. Cole brings up the comparison more directly, with the bar “Love when they argue the hardest MC / Is it K-Dot? Is it Aubrey? Or me?”

So when Budden takes this track and directly argues for J. Cole’s superiority, saying Drake isn’t acting his age, how does the 6 God respond? In the most insecure way possible — a long Instagram comment of bitter attacks under a clip of Budden’s podcast. Drake’s comment was a weird mixture of arguments appealing to his creative freedom, with plenty of personal insults degrading Budden’s past success (or lack thereof), specifically referencing how “he owns a modest house in the 973 and flies first class on special occasions.”

This isn’t the way to prove you’re not insecure. In fact, this proves Drake cares deeply about success. He clearly wants to be the G.O.A.T., to transcend his competition. The problem is, he really doesn’t care much about his own personal expression. As is clear from his targeted insults at Budden’s wealth, Drake has a weird complex where he conflates mainstream success, money and fame with greatness.

This is exactly why his album falls flat and will never be considered classic. The only way someone stands the test of time is if they take a stab at being different. Drake clearly hasn’t learned that appealing to everyone, in the end, appeals to no one. This album isn’t for “the dogs.” It isn’t even for Drake. It’s for no one at all, except success itself.