In classrooms, at least in the many ones we’ve inhabited in our K-12 journeys so far, we are told that we must learn and talk about history and its atrocities so as not to repeat them. We learn from the mistakes of those before us: We know not to mix bleach and ammonia only because someone has already done it, and we know not to get the shrimp from Nolan’s on 33rd because we’ve all had a friend who paid for it dearly.

History is not, however, solely a record of our mistakes. It is also a record of the greatest of humanity, of all the people before us who did the impossible — the people who did not get discouraged by how impossible change seemed and set out to make change happen despite knowing it would not be seen in their lifetimes. History shows a vital strength and a stubbornness that, in a world too focused on reality, we need to regain.

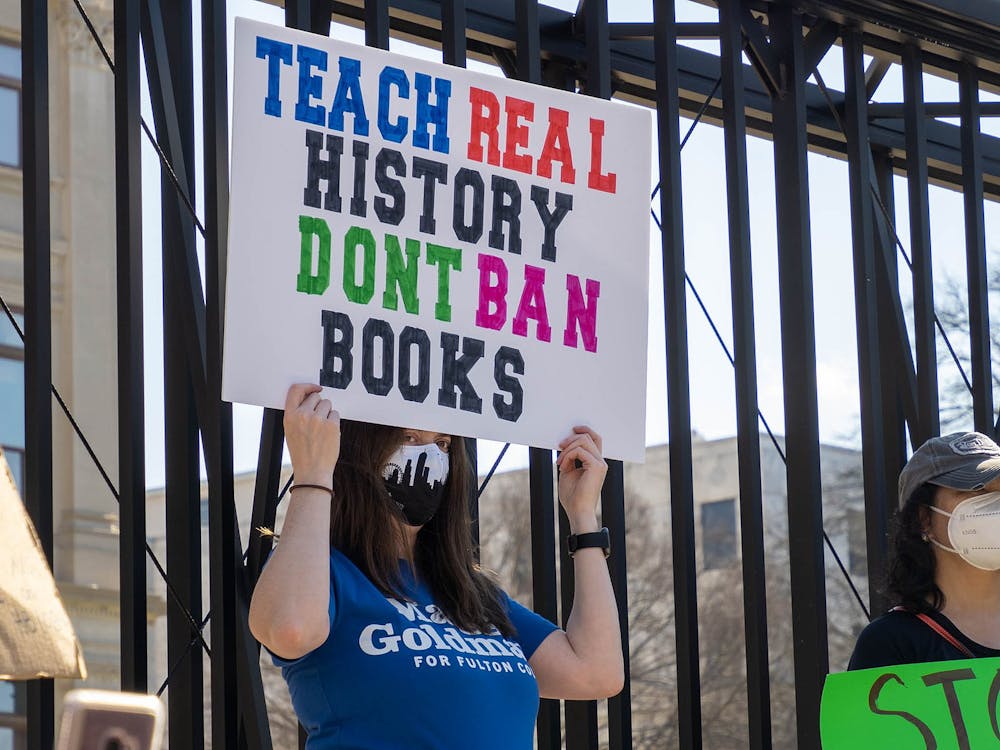

That is why attempts to hide history are so dangerous, such as Governor Ron DeSantis’ rejection of the AP African American Studies course for its alleged “agenda” of spreading political intentions and queer theory. African American history has been further censored through the banning of several Toni Morrison novels in Kentucky and Missouri, such as Beloved and The Bluest Eye and even Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in Massachusetts.

American history is ugly, especially with its relationship with race, and it is easy to try to ignore it to save face. Making it a taboo to look at the triggering or uncomfortable parts of African American history not only steals African Americans’ right to their past but also prevents them and the rest of society from benefiting from the legacy of resilience of those who fought for the luxuries we have today.

Jamelle Bouie, a columnist for the New York Times, commented on this at Hard Histories: Reckoning with Racism, Forging Just Futures, a discussion hosted by the Hard Histories at Hopkins program.

“I think a lot of Americans are just out of the habit of thinking expansively about what their country could be,” Bouie said.

We are now at a point where we look at the world around us with such a realistic point of view that, as a society, we have lost sight of the possibility of a better world, especially one in which the consequences of racism are lessened. Looking at icons of African American history, who, despite being limited by racism, discrimination and segregation, were able to imagine a world outside of the one around them, can act as inspiration for the modern generations in the U.S. to continue fighting for progress.

As Sherrilyn Ifill, a civil rights lawyer and discussion panelist at the event, shared, “The test is whether you have... run the part of the race that was assigned to you, that you have passed the baton sufficiently and pressed it firmly into the hands of the next runner.”

The race for inclusivity and equality is one full of obstacles, ones which cannot be resolved in a single lifetime. However, we must continue to believe in a better world and take that motivation to confront the problems in front of us right now, be it calling out DeSantis’ attempt to censor history or protesting states’ prohibition of books they deem ‘inappropriate’ due to their historical authenticity. By doing so, we will make it easier for generations to continue making progress toward change.

Looking at the successes of past generations underscores the importance of addressing problems even if they seem hopeless. Figures like Thurgood Marshall and Frederick Douglass chose to look at the world with possibility rather than hopelessness. Without them, strides in racial inclusion and diversity would not have been possible.

Observing how others have made the path toward inclusivity easier for us should inspire us to do the same for generations to come. It’s our obligation to grab our batons despite facing an unknown race and run with them so that others won’t have to run as far.

Yuval Cherki is a freshman from Scarsdale, N.Y, majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology. Lana Swindle is a freshman from Princeton, N.J., majoring in The Writing Seminars.