Sophomore Jennifer Hu expected that research would be part of her Hopkins experience, but that didn’t mean it came without surprises. Through the Bloomberg Distinguished Professorships summer fellowship program, Hu began working with the Huganir Laboratory, which investigates neurotransmitter receptor function and synaptic transmission.

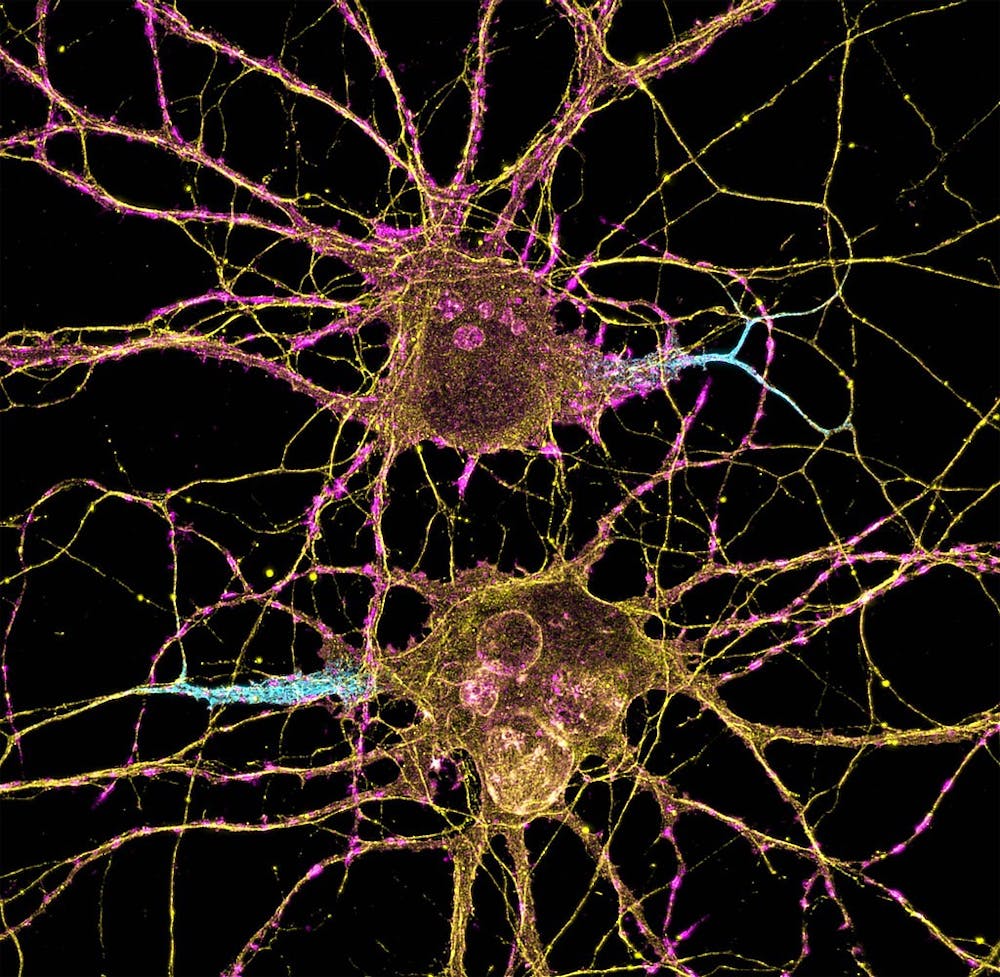

Guided by Research Associate Ingie Hong, Hu worked on two primary projects. The first is using CRISPR gene editing to create a self-excising SYNGAP gene in embryonic kidney cells, which will eventually be used to create a primate model of autism. Her second project consists of performing mice craniotomies — a form of brain surgery that creates a 4x4 mm window into the visual cortex — and then monitoring the now-visible neurons for activity in response to visual stimuli, a process called retinotopy.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Hu explained how Hong trusted her to guide her own experiments.

“My post-doc [Hong] explained to me the science of what we were doing, and said, ‘Try to figure out what you’re going to do!’ This was my first venture into research, so it was very nerve-wracking at the start, but it was a really good experience,” she said

While the summer marked her first foray into lab work, it was far from Hu’s first research experience, which began online during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In my junior year of high school, I did some independent research projects on depression, and that got me really interested in neurodegenerative disorders. You wouldn't think of depression as a neurodegenerative disorder, but it is. I was really interested in mental health and understanding how depression happens in the brain, what could lead someone to become depressed and how [we could] prevent that,” Hu shared.

With her newfound passion, she began analyzing human brain databases to find novel biomarkers for depression based on the neuroplasticity hypothesis, which postulates that depression is caused not by a lack of serotonin but by atrophying neuron connections.

Through these experiences, Hu has gained a new understanding of and appreciation for the research that goes into each and every medical innovation. This comes from struggling through the research process herself and finding the perseverance needed to continue.

“I didn't really understand how much work and perseverance research really is,” she said. “Whenever you hear about a new drug or a new discovery, you’re like, ‘Wow, they thought about it, they proved it and now it's out here.’ I didn't realize until I experienced that myself, how much failure there really is and how much you really don't understand.”

Hu attributes part of this lack of understanding to the structure of our classes up through college, where emphasis is placed on getting the right answer. The expectation is that with sufficient effort, you can find this answer, and — if you can’t — there are people who will help you find it. This, she explained, is not how true research works.

“It takes a lot of thinking and brainstorming to be able to even make an assumption of what's going on. From that, I’ve learned a lot about how I should tackle this science and hypothesizing in general. It's very different from what I thought it should have been,“ she said. “There really isn't as much straightforwardness in the world as we think there is and it takes a lot of effort to be able to stick to a question and actually figure it out.”

While research has brought Hu new understandings, it also came with new obstacles, most notably an intense phobia of mice.

“I developed a mouse phobia. It's crazy because I wasn't scared of mice before, but then all of a sudden, they can bite you and they can run around. During my first batch of mice, a mouse literally traumatized me. It jumped out of its cage and ran around the room and I was like, ‘Yikes, that's more than I bargained for.’ But I've gotten better every day. I've overcome fears doing research.”

While she continues to overcome her fears, Hu is also navigating doing work during the semester, which brings about a new host of challenges.

Students involved in research during the academic year have to balance time in the lab with classes, clubs and other commitments. Compared to summer break, when students can treat their project as a full-time job, the pace of a research endeavor may significantly decrease.

“It's a huge slowdown and made me really appreciate having a summer to do things because even though I thought my progress was so little, it was actually way more than what I'm probably going to be able to accomplish in an entire semester,” she said.

Hu also shared how grateful she was for the learning opportunities and trust given to her by her team.

“Even though I hit many roadblocks, the support and kindness from my post-doc [Hong] really helped me push through and keep enjoying the process,“ she said. “The entire lab really went out of their way to help me in any way they could and I felt really welcomed during this summer. I’m really excited to keep doing research here.”

In the future, Hu hopes to continue her work on depression and find ways to regenerate lost neuron connections, thus decreasing symptoms of depression. While her current work does not deal with depression, Hu’s interest remains strong.

“[My current work is] not about depression, but I'm hoping that in the future I will be able to circle back on that,” she said. “That's why I want to do medicine. That’s why I want to do neuroscience.”

Research on the Record spotlights undergraduate students involved in STEM research at Hopkins. The goal of the column is to share reflections on the highs and lows that Hopkins students experience in their contributions to undergraduate research. If you are an undergraduate researcher interested in being profiled, reach out to science@jhunewsletter.com.