Last Wednesday, Teachers and Researchers United (TRU-UE) held a discussion panel on potential alternatives to the Johns Hopkins Police Department (JHPD). While this event was organized by the Hopkins graduate student union, faculty members also participated and expressed support for increased community dialogue surrounding the JHPD.

If there’s one issue that has seemed to drive undergraduates, graduate students and faculty alike to use their voices, it’s the JHPD.

In 2019, students and community members held a month-long sit-in in Garland Hall to protest the planned private police force and the University’s contracts with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. Protesters even refused to leave Garland Hall after 80 Baltimore police officers arrived to vacate the building. Four students — two undergraduate and two graduate — were arrested.

This past fall, the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Faculty Senate unanimously passed a resolution expressing its opposition to the JHPD, echoing many of the concerns raised by students. In correspondence and interviews with The News-Letter, several faculty members shared their concerns about the harm a private police force could cause to campus life, Hopkins affiliates of color and the wider Baltimore community.

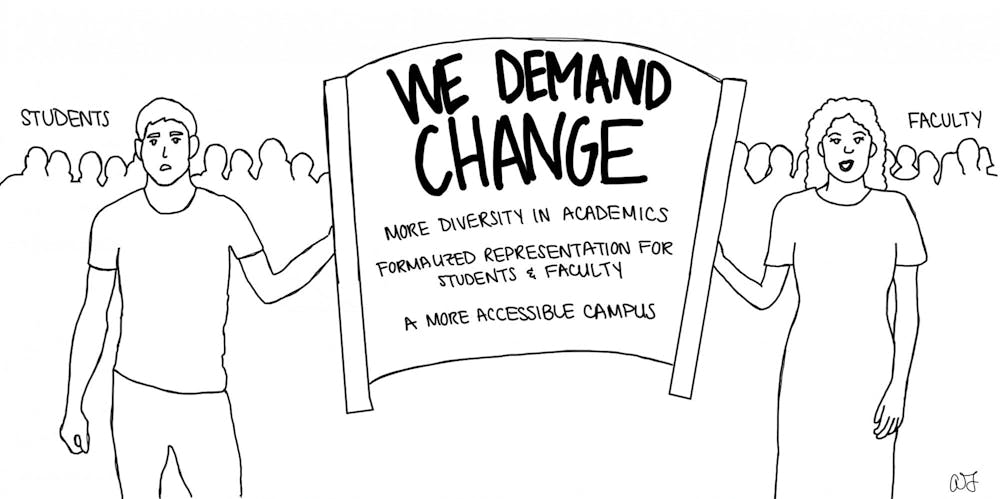

Students may see the concerns of Hopkins faculty as completely separate from their own, but both groups lack formalized representation in key decision-making processes despite being critical stakeholders in the community. As such, it is imperative that the University’s student body and faculty collaborate to address their apprehensions. By joining forces and pooling resources, they can engage in more effective dialogue and fight for adequate resolutions from administrators.

At other universities, faculty support for student initiatives has effected positive change. In November 2015, Princeton’s student body engaged in a series of protests against their university for upholding Woodrow Wilson’s legacy in its campus and building names despite his racist presidency. Over 100 faculty members across a variety of departments signed an open letter to Princeton’s administration supporting the students’ cause and expressing disapproval of disciplinary action taken against protesting students.

In response, Princeton University President Christopher L. Eisgruber asked the Board of Trustees to reevaluate how the University recognized Wilson. After five years, Princeton finally announced it would rename its public policy school and Wilson College.

Faculty-student solidarity can go both ways. At American University, the student body organized a walkout in solidarity with the faculty’s strike for higher wages and improved benefits, prompting the university to ratify a more equitable contract. Harvard’s students, faculty and even alumni joined forces to campaign for divestment from fossil fuels through the organization Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, resulting in the university’s decision to end all direct investments in companies that explore or develop fossil fuels.

At some of our peer institutions, students have more direct representation. For example, at Duke University, up to three current students or recent graduates may be elected as members of the Board of Trustees. At the University of Connecticut, two of the 21 Board of Trustees members are elected by students. Meanwhile, neither Hopkins students nor faculty are able to serve on the Board of Trustees. In the past, Hopkins faculty have called on President Ronald J. Daniels to grant faculty more shared governance.

In the long term, we hope both Hopkins students and faculty have more input in the administration’s decisions, but we know bureaucratic changes take a long time. Until we have greater representation, collaboration between students and faculty is vital to achieve common goals.

When Hopkins students and faculty have previously worked together for shared causes, they have accomplished great feats. Former University President Lincoln Gordon faced opposition from several senior professors, and The News-Letter extensively covered the controversy of his presidency. In 1971, after just four years as University president, Gordon was ousted from his position by a no-confidence vote among Homewood faculty.

Additionally, both students and faculty advocated together for the creation of a Critical Diaspora Studies (CDS) program to give students an academic space dedicated to themes such as migration and displacement against the context of white supremacy in America. Though there has been significant support for CDS, students and faculty still have to work together on ensuring the program is executed.

While it may sometimes seem that students and faculty have disparate experiences and interests on campus, the reality is that we have shared goals that would benefit immensely from collaboration. More shared governance for students is a long-term goal, and we should work toward it. However, until it comes to fruition, we must ally with faculty.

Whether it’s expressing concerns about the JHPD or a need for more representation in academics, one thing is clear: our voices will only be more powerful when exercised in unison.