With a 97% majority, graduate students at Hopkins overwhelmingly voted in favor of unionization in a union representation election, facilitated by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), on Jan. 30 and 31.

Organizers at Teachers and Researchers United (TRU), which is affiliated with United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), expressed their excitement regarding the results of the election and the culmination of their work.

In an email to The News-Letter, Wisam Awadallah, a doctoral candidate in the School of Medicine and an organizer for TRU-UE, emphasized how other avenues of advocacy were not effective, making unionization the only way forward.

“A lot of people have been working towards this for years, many graduated or left the university before they could see this happen,” he wrote. “I am looking forward towards bargaining and making sure graduate workers receive a fair contract and continue to make our voices heard.”

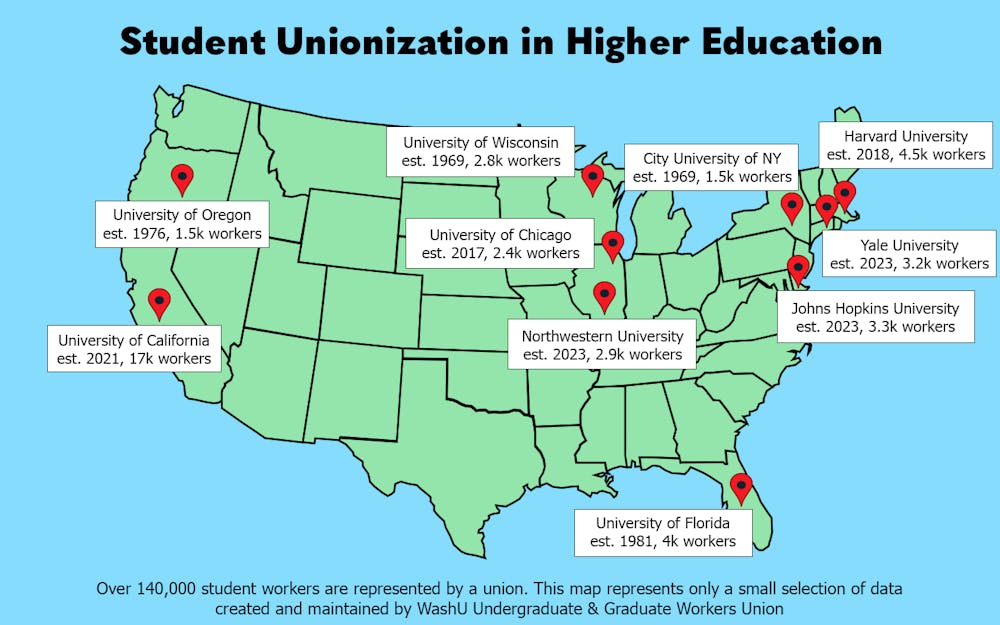

In the past few years, the rate of unionization in higher education institutions has rapidly increased. Graduate students at Brown, Columbia, Vanderbilt, Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology have successfully unionized. Even in the past few months, Yale and Northwestern University won their union elections with a 91% and 93.5% majority respectively. Other graduate student unions are in various levels of negotiations with their respective administrations for contracts.

At the University of Chicago, union elections are currently underway, and organizers are hoping to certify election results after mail in ballots are counted.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Valay Agarawal, the communications secretary for UChicago Graduate Students United – United Electrical Workers (GSU-UE), noted that the wins of the union reflected the work of many students.

“The students are running this union, and the changes that will come up at the UChicago policy level or at any level will have our voices reflected in it,” he said.

Awadallah explained that labor movements in general have seen a surge in organizing, as workers seek for fair treatment in their workplaces and wages that match the value of their labor.

“Unions offer an avenue to make our voices heard and I think more and more graduate students are realizing the power we hold and are fed up with the status quo,” he wrote.

The National Labor Relations Board

As an agency of the federal government, the NLRB is responsible for enforcing U.S. labor laws and supervising union elections. The NLRB consists of presidentially appointed officials. Consequently, the partisan nature often means that decisions around unionization change from administration to administration.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Christy Thornton, an assistant professor at Hopkins in the Department of Sociology and director of undergraduate studies for the program in Latin American, Caribbean and Latinx Studies, discussed how a series of NLRB cases from the late 1990s to the early 2000s shaped the context of unionization for years to come.

Under the Bush administration, the NLRB ruled in the 2004 decision regarding Brown University that graduate students were not workers but were primarily students. Thornton, who was also a graduate student union organizer at New York University (NYU) in 2009, explained how the results of this ruling overturned the legitimacy of some graduate unions that were already in place.

NYU, which had voluntarily recognized their graduate student union in 2001, reversed course in 2005 after the Brown decision and refused to negotiate a second contract with the union. However, with the 2008 election and shift in the political make-up of the NLRB, new waves of organizing started.

“There was a sense that the new National Labor Relations Board under Obama was going to reverse the Brown decision and make [unionization] possible again,” Thornton said. “In our case at NYU, the universities saw the writing on the wall — they recognized us voluntarily.”

More recently, the right to unionize for graduate students at private universities has been granted through the NLRB's 2016 decision involving Columbia University. The NLRB declared that graduate students were both students and workers, allowing numerous unions to file for NLRB elections.

Tipping points

Thornton highlighted the economic crisis in 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic as two major tipping points towards massive labor movements in higher education institutions.

“One of the arguments that administrations have long relied on is that we are essentially apprentices — that you put up with the terrible pay and the long hours and the hierarchy because it's giving you a shot to become the elite.” she said. “After the 2008 financial crisis, it became really clear that we were never actually going to make it out on the other side.”

Similarly, she spoke about how graduate work was particularly vulnerable during the pandemic. Thornton highlighted instances where graduate students lost their in-person teaching gigs or saw universities cut classes under austerity regimes.

“[It] created not only a situation where the kind of working conditions were more obvious, but also gave folks a chance to kind of begin talking about it and getting together and thinking about it,” she said.

In an email to The News-Letter, Renata Kamakura, Kerry Eller and Lauren Jenkins, graduate student organizers from the Duke Graduate Student Union (DGSU), emphasized how the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced numerous patterns and inequalities that existed for a long time both broadly and within Duke University.

“As classes moved online, some jobs were threatened and it was not always clear if people would still get paid,” they wrote. “The 2020s have highlighted how precarious our position as workers is and helped show the necessity of having a union that can protect our rights and help us advocate for what we need.”

DGSU is currently hosting a card drive to prepare for a union vote, and they plan to file for an NLRB election soon. They are hopeful that with new university administrators, Duke will choose to voluntarily recognize the union.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Dorothy Manevich, a member of the executive board of the Harvard Graduate Students Union affiliated with the United Automobile Workers (HGSU-UAW), spoke of how wage stagnation and increasing endowment funds were motivating factors for seeking greater compensation.

“Workers are fed up and they're especially fed up looking at university endowments that are in the billions and just getting larger, and it is increasingly intolerable to look at a university that has billions and billions of dollars and to justify your work for that university when you are making less than a living wage,” she said.

Sara Bowden, co-chair of Northwestern University Graduate Workers (NUGW), stressed that unions are becoming the standard for higher education in an interview with The News-Letter.

“This is the future of undergraduate students who have on-campus jobs. This is the future for postdocs, this is the future for non-tenure eligible employees,” they said. “This is already the current reality for so many workplaces. Right now, we're just working to make sure that we're a part of the future [and] the industry standard.”

Contract negotiations

According to Bowden, working conditions at Northwestern were negotiated on a departmental basis prior to unionization, which lacked collective bargaining. Since unionization, they discussed the current outlook for contract negotiations.

“We expect anywhere from four months onward to be at the bargaining table deciding,” they said. “We want to make sure that all of the proposals we're putting on the table are things that are prioritized and democratically decided by NUGW members and Northwestern graduate workers.”

Similarly, at NYU, Thornton emphasized the importance of making sure final contracts with the university contained clauses for rank-and-file-organizing and open bargaining.

“We wanted the whole union to kind of be involved and have a say in the negotiation process... making the process more democratic really cut against a kind of a long tradition that existed within the UAW of negotiating behind closed doors,” she said.

While negotiations took longer because of the open bargaining process, which were often contentious, Thornton appreciated the opportunity for all union members to voice their opinions.

Manevich described how HGSU-UAW signed a one-year stopgap contract during the pandemic to enshrine some protections for workers and won a second contract in 2021, which lasts for four years and includes provisions for increased wages. She highlighted that negotiations with Harvard have been contentious, with both periods including strikes.

“They will paint a picture of a very generous contract that they are offering when, in reality, they are offering bread crumbs, if that,” she said.

In an email to The News-Letter, Assistant Vice President for Media Relations and News J.B. Bird emphasized that the focus now is on working productively with the union. He reiterated Provost Sunil Kumar and Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education Nancy Kass’ statement from last week’s email to the community.

“As the birthplace of doctoral education in America, we recognize this as an opportunity to ensure JHU continues to build on its legacy of not only providing world-class doctoral education and training but developing innovative new approaches to supporting our PhD students in achieving personal and professional success” they wrote.

Thornton expressed her excitement that graduate students will have the space to discuss equity and fairness and will be given a living wage.

“I think [unions] only strengthen the kind of research and teaching that our students are going to be able to do,” she said.