The Peabody Institute was founded by George Peabody as a cultural institution for the citizens of Baltimore in 1857. Today, the George Peabody Library houses Special Collections, hosts private and public events and ensures that its materials are accessible through public engagement programming and the digitization of collections.

Originally from Massachusetts, George Peabody’s business career started in Baltimore, where he shipped goods between Europe and the United States. By 1837, he moved to England and was making the majority of his wealth as a banker.

In recognition of where he got his start, he endowed the City of Baltimore with $300,000 in 1857, which amounts to approximately $10.3 million today, to establish the Peabody Institute.

In his founding letter, Peabody specified that the institute’s purpose is to provide an art gallery, a lecture series, a music conservatory and a free public library.

“I have determined, without further delay, to establish and endow an Institute in this City, which, I hope, may become useful towards the improvement of the moral and intellectual culture of the inhabitants of Baltimore, and collaterally to those of the State; and, also, towards the enlargement and diffusion of a taste for the Fine Arts,“ he wrote.

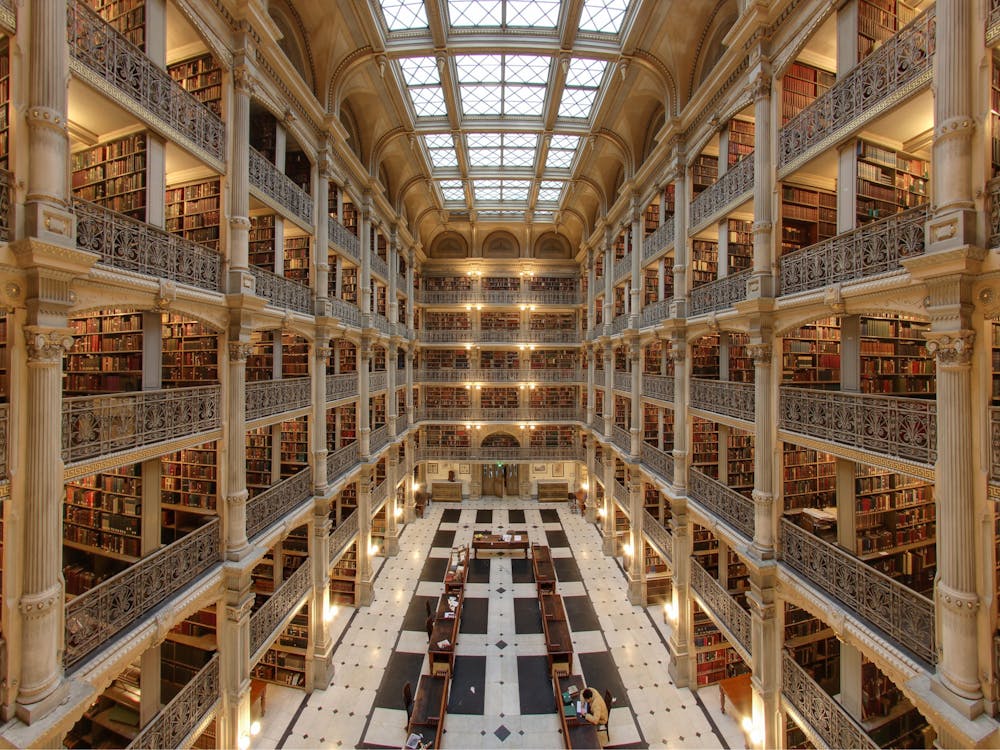

In an interview with The News-Letter, Paul Espinosa, curator of the Peabody Library, explained that the structure was originally built to house 100,000 books, but the collection soon surpassed that.

“Even though the Institute was founded in 1857, by 1875 they realized they needed much more space for the growing library. It took them about three years, but by 1878 they'd completed this beautiful building,” he said. “They reached capacity and filled up the library by about 1930. There aren't too many books in the collection that are past that date; most come from the late 1800s, early 1900s.”

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

This is a lithograph of the Peabody Institute library interior, drawn by Kees & Boyden and printed by the Heliotype Printing Company.

By 1966, the Peabody Library became part of the Enoch Pratt Public Library system. It was ultimately turned over to the Special Collections department of the University in 1982, where it remains today.

Espinosa highlighted how Hopkins has conserved the space, installing air conditioning and fire protection, renovating facilities and completing cleaning projects while retaining the original structure.

“When Hopkins took over custodianship of the music school and the library, it was in need of some tender loving care. Now, this all predates me, but from what I understand they did a major cleaning project in 1978,” he said.

While the transition of ownership facilitated restoration projects, it also impacted the Institute’s interaction with the surrounding community.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Spencer Hupp, a library and humanities postdoctoral fellow conducting research at Peabody, discussed how the change ultimately shaped public perceptions of the library.

“[During] the transition between Peabody being picked up by the University, one of the public fears was that the library would be privatized, but it's one of those great compromises that it’s a completely public edifice attached to a private institution,” he said.

He outlined how the Peabody Library navigates being both a public and private space. Though it is open to the public, a visitor needs to show identification to security to go to the bathrooms, as they are located within the private spaces of the Peabody Institute.

Hupp also described the differences in how the Peabody Library and the Enoch Pratt Library are used and regarded by Baltimore today.

“The perception of the Peabody Library, although it is a public library, is a little bit cloistered in comparison to the Pratt Library, the other big book library in downtown Baltimore,” he said. “[The Pratt Library] is a lot more integrated with the city of Baltimore, and unlike Peabody, is a library from which they circulate books. That means that the Pratt Library, through necessity, is more of a functioning urban public organ.”

In addition to changes in library ownership, the wider history of the country has also shaped Peabody Library’s interaction with its surrounding community.

While the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, racial inequality remained rampant. The implementation of Brown v. Board of Education’s ruling was especially challenging in areas like Baltimore, where the distinct property areas that fund public schools are also divided by racial lines.

Looking further back and in relation to the Peabody Institute, the music conservatory did not admit African American students until the late 1940s, despite many music programs in Baltimore having a history of doing so well before.

In terms of how this applies to the Peabody Library, Espinosa explained that the library’s history is being investigated with an eye toward exploring potential prejudice.

“Were there any stated or written policies about segregation? We just haven't found anything. It doesn't mean that there weren't some of these unwritten expectations or rules. With the cultural temperature of the time, it's hard to say,” he said. “We are actively investigating some of these things.”

Sam Bessen, the Eleanor and Lester Levy family curator of sheet music and popular culture at the Sheridan Libraries, spotlighted clues regarding the climate of the library in an interview with The News-Letter.

“My understanding is that originally it was a segregated space, both in terms of race and gender. I haven't been able to find any pictures of this, but there are descriptions of the space that date back to the 19th century,” he said. “The quote I'm thinking of is one where the ladies were complaining that there wasn't enough room to hang up their coats. Little hints about how the space was used back then.”

In recent years, the library has focused on creating public programming, increasing the accessibility of its resources and hosting local and diverse performers.

In the Stacks, a free performing art series that started in 2016, showcases connections between music and different forms of art to engage the public with the collections at Peabody.

According to Bessen, the intended impact of these programs was to find connections between music, art, literature and architecture and to find new ways of bringing people into the arts scene.

“I ended up hearing from a mom who brought her whole family to see a concert that she wouldn’t have been able to afford otherwise, saying that two of her kids now wanted to play violin,” he said. “That was feedback that let us know we're on the right track.”

Additionally, Peabody Library collaborates with different organizations across Baltimore. As part of the Peabody Ballroom Experience, for instance, the Peabody Library has recently begun hosting an annual LGBTQ+ dance event where the performances are informed by books in the collection.

Accessibility has also been approached through the lens of technology by digitizing certain parts of the Special Collections.

“The University is a well-endowed, wealthy institution [that] has not just financial wealth, but material wealth. The library exists to house the University's collections but that doesn't mean anything without accessibility, which is at the heart of what the modern 21st-century university is about,” Bessen said. “You can look at the bookshelf virtually and browse the books within a given span. It’s democratizing a physical space.”

This digitization of collections, such as the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, facilitates its use by students, faculty and professors for both personal and instructional purposes.

Vanessa Han, a freshman fellow researching Middle East-inspired sheet music collections at Peabody Library, shared her surprise at the multitude of resources available to Hopkins affiliates through digitized collections.

“If I weren't doing this research, I wouldn’t know that there were so many resources available to me. Anyone could make an account on Aeon and explore Special Collections on their own time or do a research project on them,” she said.

Espinosa reiterated this idea, emphasizing that the library wants visitors to engage with the contents of the books and the history of the space.

“We want [undergraduates] to actually understand how knowledge has come down to them, whether it's the liberal arts, the humanities or even history of science,” he said. “Nothing makes quite the impression on a beginning biology student as seeing the first edition of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Or the first edition of Galileo or Newton to a physics major. That’s what we try to do today.”