I am much better at buying notebooks than I am at finishing them. In fact, I have a sizable collection of half-used notebooks, journals and diaries filling my bookshelf at home and my desk drawer here in Baltimore.

My collection is eclectic — I’m attracted to well-designed covers, intricate bindings and unique features. I have a Rhodia, a Kokuyo Smart Ring Notebook (which is more of a thin binder), several Moleskines (which, according to this person and these people, are completely overrated), a floral handstitched Nathalie Lété notebook and many, many more.

Much of the reason why I have so much trouble finishing a notebook is my short attention span and my perfectionist tendencies: I’ll start a notebook, intending it for a specific purpose, lose motivation to continue using it for that purpose and then completely abandon it because it’s no longer pristinely untouched.

In the grand scheme of extended metaphors, my notebook habit is perhaps indicative of a larger pattern of behavior. It represents the things half-done: half-finished stories, half-finished work, half-pursued goals.

My writing in particular mimics the trend of my notebooks. Like the unfinished notebooks filling my bookshelves, unfinished stories fill my Drive storage space. These WIPs, or works-in-progress, are a testament to the many ideas swimming in my head and my lack of self-discipline to follow through with them.

Finishing these WIPs is difficult for me because I am resistant to the revision process. I hate working on what I perceive to be an imperfect work. I’d much rather start on a new idea and hope it ends up better than my previous ones.

In my ideal world, a piece is flawless from the start, and, other than minor grammar and wording edits, revision is unnecessary. This is contrary to what some say, that revision is where the real work of writing happens. Changing my mindset to embrace revision as a necessary, expected and essential — not additional but integral to the very idea of writing — is a slow-going endeavor.

Last year, I was introduced to the concept of a commonplace book.

Unlike bullet journals, diaries or other notebooks, a commonplace book is less a gathering of deliberately chosen, curated material and more a resting ground for the miscellaneous. In other words, it’s the scrapyard of notebooks.

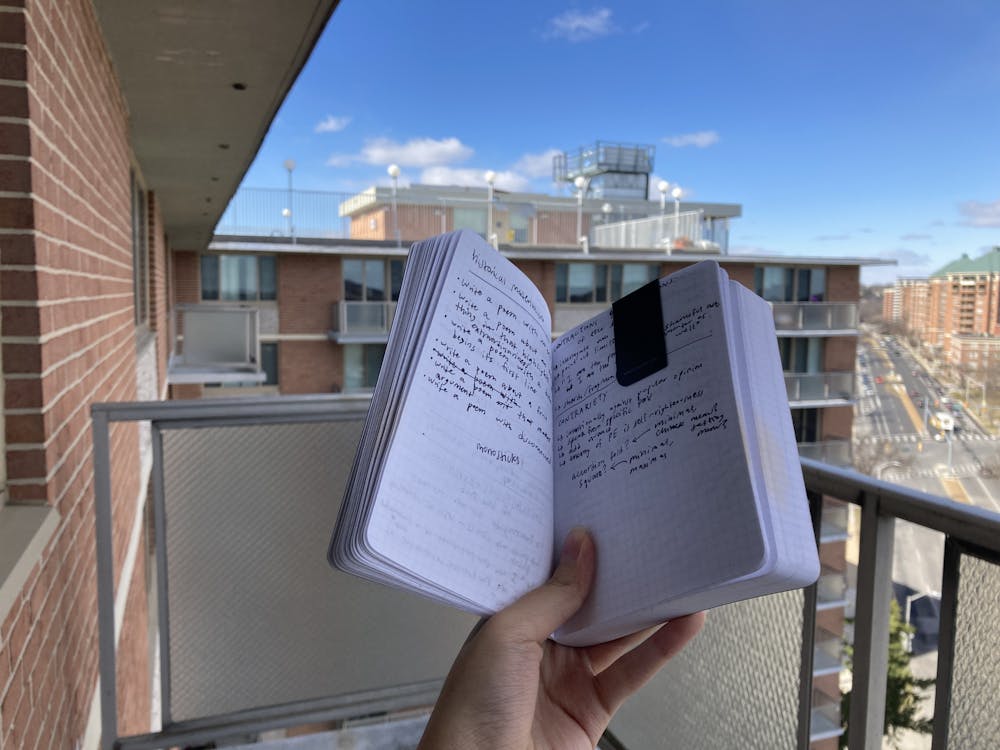

Commonplace books can vary in how random and haphazard their contents are, but, for myself, my commonplace book has very little structure to it. I’ll fill it with endless to-do lists, jot stray notes from class, journal my thoughts on a situation, record ideas for stories and write down song recommendations from friends.

The very nature of the commonplace book facilitates its completion. Without a formal structure and because it, by definition, can be filled with pretty much anything, there’s no risk of my losing motivation to finish it; every page can be used for some new and unique purpose.

The looseness of this structure is what has allowed me to actually complete a notebook — from cover to cover — for the first time in a while. Flipping through the book, I’m able to retrace the past semester as each jotting, scrawl and list documents minute moments of my life.

In some ways, it’s a very mundane form of journaling, one that focuses on the routine as opposed to the most emotional or eventful. Here are a few of those mundane writings that I’ve found looking through my notebook:

- Plans I had for the summer, both fulfilled and unfulfilled

- Early ideas for stories that have now transformed into completely different works

- Notes on each high school student from my summer teaching internship

- Shopping lists for furniture and household items for my new apartment

- Calculations for splitting a bill between eight people after someone’s birthday dinner

Completing a commonplace book isn’t about making something perfect or pristine; it’s just about making. In that vein, I want to adopt a more flexible, unrefined view of my writing. My pursuit of the perfect work can discourage me from making any work at all.

By embracing the inherent and expected imperfections of my initial drafts, I can begin to see revisions as a more natural next step as opposed to an indication of a flawed work, and, eventually, I can produce more complete, finished writing.

Aliza Li is a junior from Houston, Texas studying Writing Seminars. She is the Voices Editor for The News-Letter. Her column discusses her journey as a writer and how words have transformed her life.