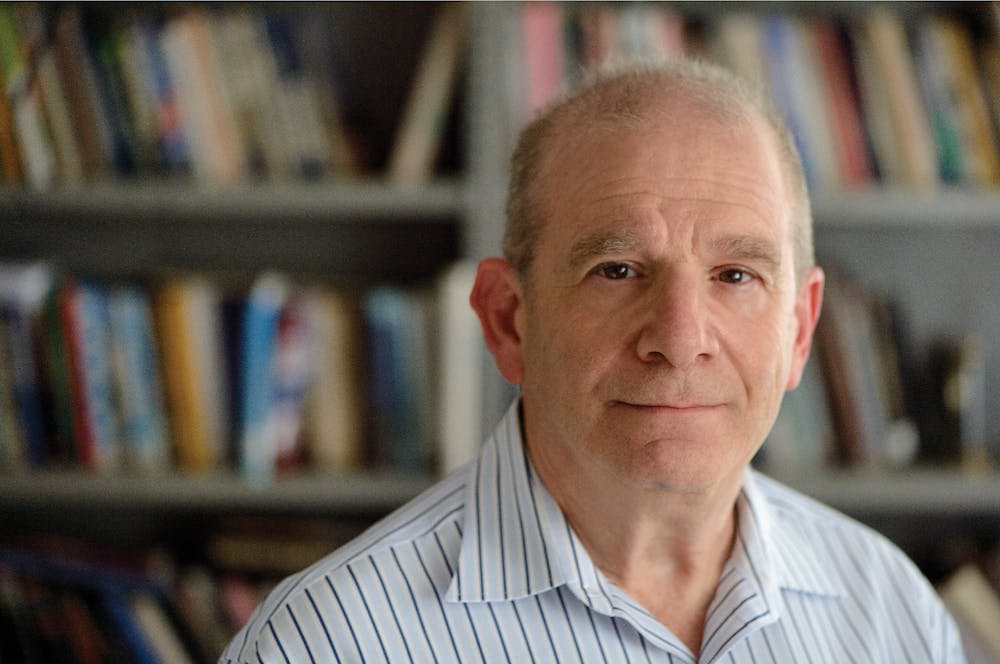

Steven David is a tenured professor of International Relations at Hopkins. During his 40 years at the University, he has taught classes on nuclear weapons and political violence as well as on peace and war. He is currently writing two books, the first focused on Sino-American competition in developing countries and the second on threats to Israel's existence. In an interview with The News-Letter, David discussed his journey into academia, his current projects and advice for students.

The News-Letter: Why did you go into academia and Political Science specifically?

Steven David: I've always been interested in some of the big issues in international relations, like why countries go to war, how we can achieve peace, how we can make life better for people in the developing world. To answer that, in grad school, I spent a couple of summers in the government and state department. I liked it, but it was very bureaucratized, so I preferred academia.

N-L: When you think back about your adolescent years, were there any particular things that sparked that interest in international affairs?

SD: I was born in 1951. I knew a lot of older people who served in World War II, including my dad. The stories about World War II and learning about the Holocaust deeply affected me and [made me realize] we're in a very dangerous world… and [made me think about] how we can make perhaps more favorable, and less menacing.

NL: Have you encountered any difficulties on your journey, academic or otherwise, that you think students could learn from?

SD: In academia as in life, we always encounter difficulties. It’s a bit of a cliche, but we learn more from setbacks and successes. I've had my share of setbacks, maybe my share of successes, but I've been very happy in academia. It's a life where you can structure your own time, work on things that interest you. At Hopkins you get to interact with great students, both undergraduate and graduate, and great colleagues. It's been a real treat to have had this experience.

NL: What keeps you passionate about your work and engaged with teaching?

SD: I’m enjoying a writing project [about China].The students at Johns Hopkins are great. They’re smart, they’ve worked hard to be surrounded by students who are like them, and they come here to get a challenging education.

N-L: Can you share more about the book project on China?

SD: China has emerged as a superpower, a competitor to the United States, and one of the arenas for that competition is in the developing world. To a certain extent, this reflects the U.S.-Soviet competition during the Cold War, and we draw on some of those experiences to see what exists in common and what is different from the competition today. Some of the questions I'm asking are: Which country is positioned to attract influences? Why should this competition even take place?

N-L: Your bio says you’re also working on a book about Israel. Can you speak a little about that?

SD: Israel deals with existential threats. It has existed since Biblical times but has been destroyed as a state or entity [on multiple occasions], and many of the reasons for its destruction resonate today. Some of [the issues stem] from outside threats, but a lot of [them stem from] internal strife and internal divisions. Especially since the recent elections in Israel, there is a strong, right wing, religious government. Israel struggles to remain both Jewish and democratic. There are questions as to whether [Israel] can maintain that balance into the future, and we teach a class called “Does Israel Have a Future?” where we examine these existential threats.

N-L: What is the biggest piece of advice you have for students?

SD: Well, I hate giving advice because it could be misunderstood or just plain wrong. I guess if I could give some advice, it would be to relax. Hopkins students tend to be driven, which is something that is good because it helps them succeed academically and professionally, but although you’ve got to do some planning, things have a way of working out. Don’t always assume the worst, because you don’t know exactly which path you are going to take now. Enjoy life as much as you can. Don’t work all the time, though I probably shouldn’t say that since I’m a professor.

N-L: Do you have any insight for people who are looking to go into academia specifically?

SD: It's a difficult path, and the job market has been tough forever. It's an uncertain future. If it's something that calls out to you, if it’s something that you want to do, you should persevere. You should have a plan B. If things don't work out in academia, you'll want to have something to fall back on. One of the nice things I see in your generation is that students seem more willing to explore. [It used to be that] you went to school, then to college, then to grad school or professional school and then to your job. Nowadays, I see students doing different things like working in construction or in restaurants. The parents go nuts, but it’s a really good experience and then a few years later, they find more of a direction and pursue that. People change jobs and careers more often now than they used to, and I think that’s healthy.

I grew up in the South Bronx, and sometimes I think that influenced my international relations career because the South Bronx is a lot like international politics. You have anarchy, the use of force, ethnic conflict, the futility of appeasement. But my summer jobs that were most memorable were not typical jobs [for a Political Science major], like Congress or a government agency, [but they were things like] the post office, or the neighborhood youth corps, and I got to meet a set of people there I wouldn't [otherwise have met]. One of the things that concerns me about society today is that [many people] don’t meet people from different backgrounds as often, but summer jobs can give you that opportunity, especially if they’re not traditional academic jobs.

N-L: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

SD: One of the things I’ve been worried about, of course, is the state of the world. It’s been over 80 years since there’s been a great power conflict, since World War II. It’s the longest period of peace among great powers in world history. And I’m worried that that may be breaking down, between the American-Russian conflict, the Sino-American conflict — so I’m worried about that. We haven’t used nuclear weapons since 1945, and now there is the possibility [of that happening] in Ukraine.

But for all of these external threats — we focus on international relations and threats from other countries — I think the biggest threat to the United States today is domestic. I think perhaps the biggest mistake I made as a Political Science professor was thinking that American democracy is secure — that we will have different sides of government, different levels of taxation, this policy versus that policy. But for the first time I’m seeing fundamental disputes about what democracy means, what truth is, and how we move forward. And this is really scary because whatever our enemy is trying to do to us is not going to be nearly as harmful as what we do to ourselves.