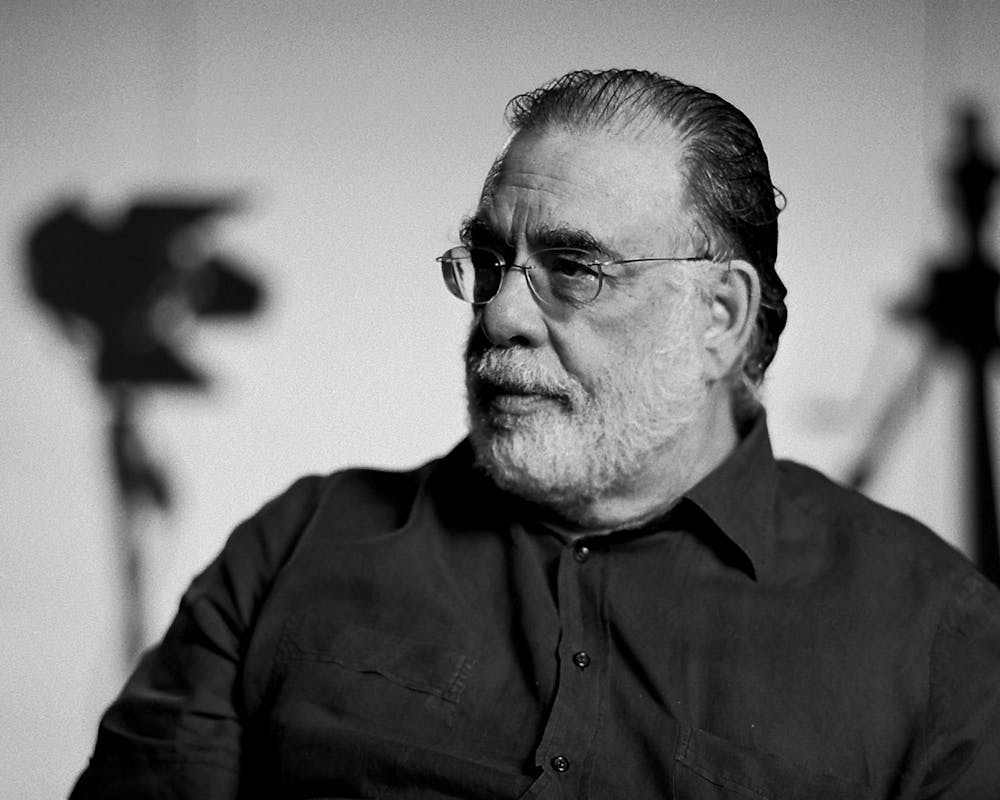

Anyone who doesn’t believe in miracles has clearly never seen Apocalypse Now. Directed by the legendary Francis Ford Coppola (director of The Godfather trilogy), Apocalypse Now is epic in all proportions and stands out even among the greatest of war films. There is no aspect of the film — from its production to the very fact that it was actually completed — that isn’t wildly fascinating.

Set in the Vietnam War, Apocalypse Now has everything and nothing to do with war. The movie follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) on a top secret mission as he traverses the Nùng river with a U.S. Navy patrol boat to reach an outpost in Cambodia. His mission is to assassinate Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), an American officer who has gone rogue and formed a cult of American and Montagnard troops.

His followers view him as a god, and he commands them into guerrilla warfare against Vietnamese communist forces without the permission of the US army. His tactics are brutal, replete with beheadings and sacrifices. As Willard goes through the dossier on Kurtz while on the boat, he learns about the unadulterated evil that lies at the end of the ride.

The film is a boat ride through the Vietnam War for both Willard and the audience, for that’s what Apocalypse Now truly is — a journey. Both Willard and the audience slowly learn about Kurtz, a prodigy of the army and an accomplished officer whose outlook on the world changes amid the horrors of Vietnam.

Apocalypse Now’s dark fantasy sets it apart from all other war films. Coppola doesn’t just make a film about war; rather, he uses it as a backdrop to explore profound moral questions, like the irony of Willard’s mission to kill his own countryman.

The moral and psychological themes that Apocalypse Now navigates are too extensive and intense for me to adequately explore here. The film itself takes three hours to do it, so clearly this column is not going to even scratch the surface. Suffice to say, watching a man prepare himself for the purest evil on Earth as he passes through a scene as horrific as the Vietnam War is a philosophical experience like no other.

However, its themes and dialogue aren’t remotely where the brilliance of the film ends. It justifies its lengthy run-time with some of the most exciting sequences in cinema history. The most notable example is Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall), an officer who bombs an entire Viet Cong coast along the Nùng river to surf on its apparently ideal waves.

Moreover, he commits his atrocities to the soundtrack of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” The exploding forests of Apocalypse Now from this sequence are now striking representations of the Vietnam War, and Kilgore’s iconic line, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” sums up the insanity of the war.

Kilgore is perhaps the most memorable character in the whole film. It’s beguiling to see someone so cruel and murderous have such a heartfelt personality. His passion for surfing is comically endearing, and Duvall plays the character with such zeal that his liveliness is infectious.

Finally, when we reach Colonel Kurtz, played by no other than the great Brando, we witness the horror we’ve heard about throughout the film. Kurtz is a god and an enigma. Even in person, he remains an idea — a cumulative representation of the evil that brewed across Vietnam during the war. After Willard makes his decision on what he must do, the film ends as it starts — a dream-like haze to The Doors’ iconic song ‘The End’.

The production of Apocalypse Now is infamous for its length, scale and chaos. Shooting went well over budget and schedule. A typhoon initially destroyed the set, and Coppola changed his lead actor from Harvey Keitel to Martin Sheen within a month of shooting. What was planned to be a four-month shoot ballooned into almost a full year of grueling production in the Philippines.

Since he was funding the film independently, Coppola went into massive debt for the film. As disasters piled up, it seemed like he had dug himself a hole without an escape. This fascinating saga was captured by his wife Eleanor in her documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse.

Nevertheless, principal photography finally ended in May of 1977. It had survived Sheen’s near-fatal heart attack at age 36 and a massively overweight Brando who couldn’t even stand for his wide shots and needed a body double to come in. Yet, that wasn’t the end of Coppola’s struggles, for the year-long shoot had left him with a million feet of film to edit.

Apocalypse Now was eventually released in August of 1979 after multiple screenings of ‘work-in-progress’ cuts, including at the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Palme d’Or. Luckily, it performed well at the box office and was a major critical success.

It is truly a miracle that this film was finished. Coppola’s perseverance was superhuman and his vision unprecedented. Apocalypse Now remains one of the greatest epics of all time and one of the biggest enigmas in cinema history. Watching it is a journey for the soul and an education unto itself, one that should be experienced by everyone in its grandeur on the biggest screen possible, again and again, forever and ever.

Varen Talwar is a sophomore from India studying Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. He is an Arts Editor for The News-Letter. His column focuses on world cinema, seminal works in cinema history and cinephile culture in Baltimore.