Hopkins has been involved in psychedelics research for decades, releasing several papers investigating the clinical usage of drugs including psilocybin in treatments of depression and other mental illnesses. A recent paper published by the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research continues this tradition.

The study ”Efficacy and safety of psilocybin-assisted treatment for major depressive disorder: Prospective 12-month follow-up” followed 24 patients for a year after two psilocybin treatments for major depressive disorder. Researchers reported large decreases in depressive incidents, with patients showing a decrease from a 22.8 baseline mean score on the GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale to 7.7 at 12 months post-treatment.

Researchers utilized a combination of psilocybin treatments alongside intensive psychotherapy sessions with team members before and after treatments. Medical Director of the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research Dr. Natalie Gukasyan discussed their findings in an interview with The News-Letter.

“It seems like the intervention that we're offering for some people can be quite helpful, and it can have a long-lasting effect,” she said.

Nonetheless, Gukasyan cautions against reading too much into these results due to the difficulties in studying long-term effects.

“There are so many confounding factors that can happen along the way, and we observed plenty of them during our follow-up study, namely that people started other kinds of treatment, including psychotherapy or doing other medications,” she said.

Gukasyan noted that research into psilocybin and other psychedelics has drastically changed since she first became involved in the field, as popular interest and scientific support for practical uses of the drug continue to increase.

“I was always really interested [in psychedelics, but] back then it was still quite taboo, and I didn't really think that it would be a viable career path until much later in my career,” Gukasyan said. “2018 was kind of the watershed moment, after which there's quite a tremendous increase in public interest in the so-called second psychedelic renaissance. We had been struggling to get funding, but that seems to be changing.”

Recently, major organizations such as the National Institutes of Health have committed to fund more research with psilocybin.

Most notable are ongoing trials by COMPASS, Usona Institute and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, which plan to return results in the next two to five years. Upon their completion, the Food and Drug Administration will reevaluate clinical usage of psilocybin, possibly opening it to broader clinical use.

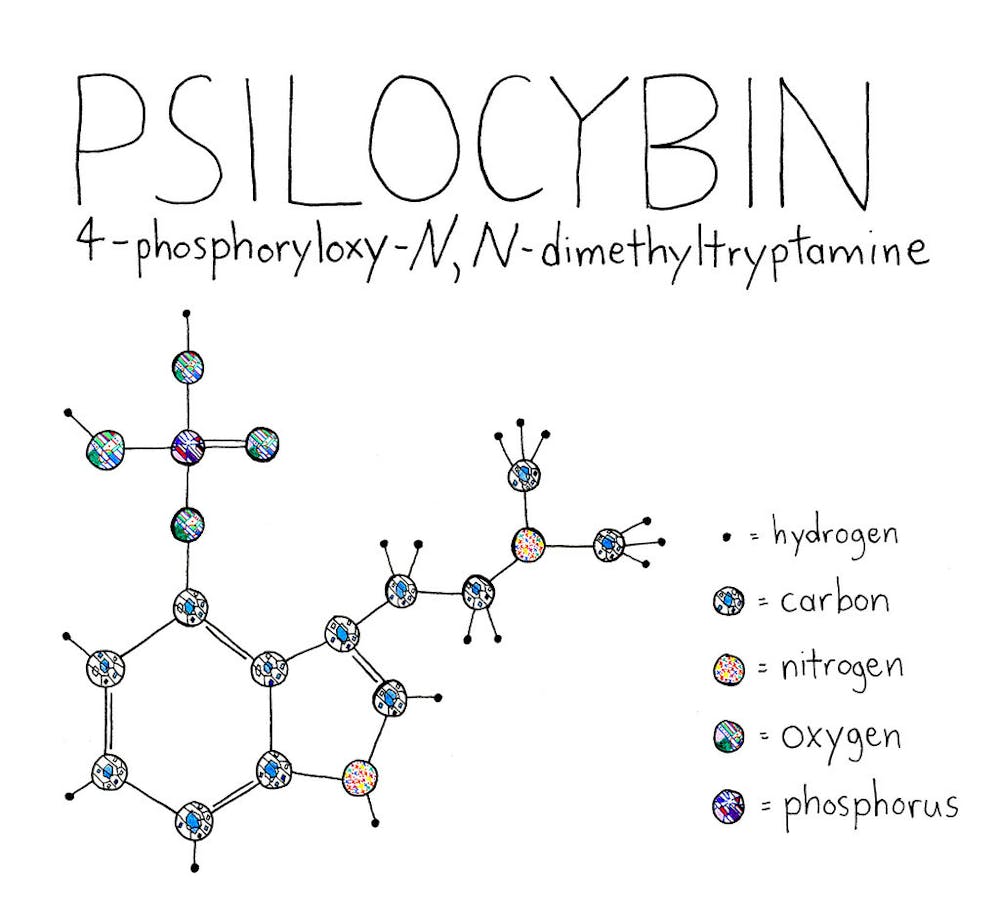

While the impacts of psilocybin are increasingly understood, the mechanisms behind them are not. A variety of hypotheses explain how psychedelics impact the brain, including working directly with chemical signals (similarly to current antidepressants), possessing anti-inflammatory capabilities, increasing brain connectivity or altering an individual’s mindset with “mystical experiences.”

While psychedelic treatments may offer meaningful interventions in the future, Student Government Association (SGA) Freshman Class Senator Jean Zhou expressed hesitancy toward their medical usage in an interview with The News-Letter.

“Although the risk of addiction and other side effects are low, the use of psilocybin would still alter people’s perception of time and space... [as a result] it should be taken as the last option,” Zhou said. “It would be great if there could be more data on a larger, long-term scale to be more assuring.”

In her role as an SGA senator, Zhou has been pushing for better student mental health support, citing the University’s limited mental health services, which often force students to seek outside providers, and the difficulty for students of taking advantage of Hopkins Hospital resources.

“[Hopkins Hospital] has the number one psychiatry department, so it could be potentially very helpful if they can offer either services or research that's more accessible to students here, which is not the case right now,” Zhou said.

While psychedelics are far from being approved for use in college students, Zhou encouraged further examination.

“It’s definitely worth the effort to pursue and see more potential progress in development,” Zhou said.

With research continuing into the future, Gukasyan explained the necessity of ongoing psychedelic investigation.

“This might represent a very powerful tool and alternative to treatments that we have available for a variety of mental health issues,” she said. “We need more research on rapidly acting therapies; this seems to be a potential treatment that can have durable benefits.”