Last month, the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) launched from French Guiana, and after a long journey, the telescope reached its final destination yesterday afternoon. While Webb is a global effort involving tens of thousands of scientists and engineers and billions of dollars, its heart is right in our backyard.

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) serves as the science and operations center for Webb, in addition to the Hubble Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

The Hubble telescope measures wavelengths of light between 0.1 to 2.5 microns, observing the ultraviolet and violet ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum as well as a portion of the infrared range. In contrast, Webb is almost exclusively an infrared telescope, focused on wavelengths from 0.6 to 28 microns.

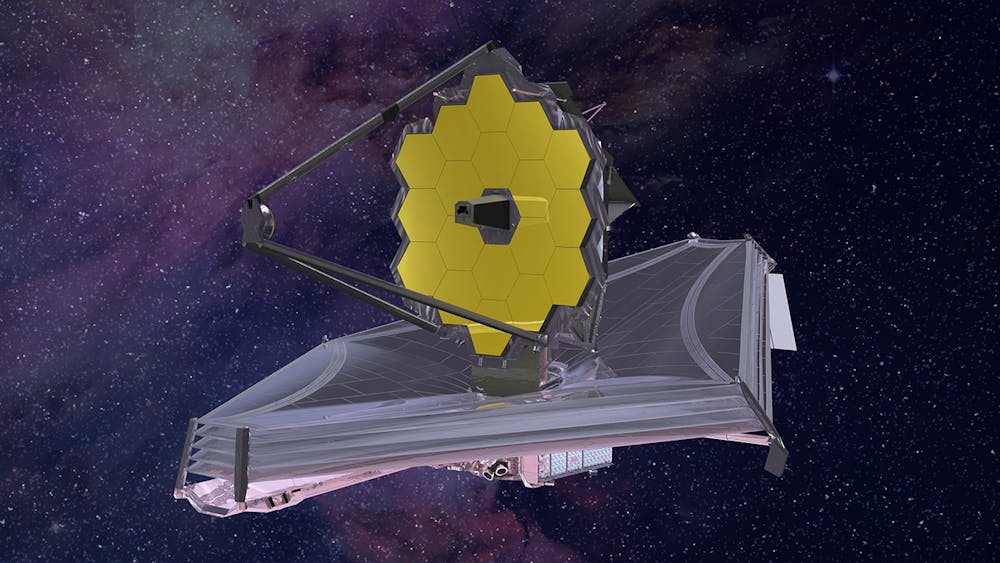

Additionally, Webb’s primary mirror — 18 hexagonal segments of gold-coated beryllium — possesses a 6.6-meter diameter, a 275% increase compared to Hubble’s 2.4-meter mirror. This larger diameter enables Webb to have greater resolution.

Christine Chen, associate astronomer at the STScI and research scientist at Hopkins, discussed the purpose of building an infrared telescope in an interview with The News-Letter

“Webb was originally designed to look at the very first galaxies after the Big Bang,” she said. “These are objects that are very distant and then therefore very faint.”

To catch the faint emissions of the early universe, Webb has been isolated from as much infrared radiation as possible. Webb utilizes a tennis court-sized sunshield capable of creating a 360-degree Celsius temperature gradient to block the heat of the sun. Additionally, it is situated around the second Sun-Earth Lagrange Point, which maintains position relative to the Sun and Earth over 1.5 million kilometers from Earth to ensure no interference.

From this vantage point, Webb will turn to the heavens its four instruments: mid-infrared instrument, near-infrared camera (NIRCam), near-infrared spectrograph and near-infrared imager and slitless spectrograph/fine guidance sensor.

Hopkins Research Scientist and Branch Lead of NIRCam Massimo Robberto, who has worked on NIRCam since 2005, explained that in addition to serving as a measurement instrument, NIRCam is essential to ensure the proper functioning of the telescope.

“[NIRCam] is the primary instrument, mostly because it’s the instrument which has the job of keeping the telescope aligned and in phase, [ensuring] the 18 mirrors work as a single mirror,” he said in an interview with The News-Letter. “To do that, you need to move the mirrors and look at the image quality and analyze what’s coming out and this is done with NIRCam. [It’s] both for science and to keep the telescope up.”

The initial mirror alignment process began on Jan. 12 and was completed on Jan. 20.

While Webb was initially designed to see long into the past, advances over the past 30 years have also turned increased attention toward nearby exoplanets, which Webb’s sensitive instruments will study in greater resolution. Ensuring that Webb is capable of satisfying the research aims of astronomers has been a goal of Chen’s for the past 13 years.

“Webb had been designed toward looking at these very distant galaxies. Now all of a sudden, we're very interested in looking at transiting exoplanets, and the sources for transiting exoplanets are vastly different — they tend to be around nearby bright stars,” Chen said. “You can imagine that you have to enable different modes of operation in order to accommodate looking at bright stars and also at very faint things. That’s some of the work that I did early on.”

Chen and Robberto, alongside 700 other scientists and astronomers, are employed at STScI, which was founded by NASA and the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in 1981 as the science operation center for Hubble. In an interview with The News-Letter, Deputy Director of STSci and Hopkins Research Scientist Nancy Levenson commented on how STSCI bridges the gap between space technology and its research applications.

“Going back to the founding of the STScI 40 years ago, there was a realization on the part of NASA that they needed an organization to be a stronger connection to the scientific community, [STScI] is this bridge from what you might think of as the more technical or engineering side of the mission to the science,” she said. “That’s why the STSci was proposed to be on the Hopkins campus to be well embedded in an active research environment.”

STScI’s work can be divided into three main tasks: operations, calibration and data reduction. Operations ensures that instruments are utilized in accordance with the needs of the scientific community, calibration ensures that instruments are able to properly interpret their measurements and produce useful data and data reduction aims to package that data for analysis.

According to Levenson, scientists will operate and supervise the daily operations of Webb from STSci.

“We conduct proposal review processes and do the selection. Those scientists wind up doing the technical development of their programs [including] exactly how they want to use the instruments for, and we support them through that process,” she said. “Our folks also do the planning and scheduling, so that [programs] get observed at the right times. We support the instruments so that the data are useful and ultimately deliver them back to those scientists.”

In addition to operating Hubble and Webb, STScI runs the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, a depository of space telescope data available to the public and produces images for mass distribution.

According to Levenson, keeping these resources accessible is important for fostering discovery.

“The fact that anyone, any researcher around the world, any eighth grader who's just really interested can take the data and do what they want with them opens up a lot of opportunities. There's a lot more science that gets done beyond what was originally planned,” she said.

Levenson asserted that the collaboration between STScI and Hopkins runs deeper than mere location. With staff members sharing joint appointments, mentorship, research opportunities for graduate and select undergraduate students and a series of cosponsored labs, STScI is embedded in the research culture at Hopkins.

“There are a lot of good connections and collaborations between STScI scientists [and those] who are part of Hopkins. For research that feeds new things, being colocated with the university is really helpful,” she said.

While Webb will undergo several months of testing prior to initiating scientific observation, the first images are expected to be published around July. Several Hopkins astronomers, including Chen, are slated among the first phase of Webb observers who hope to use the observatory to shed new light upon their research.

“I'm super excited to look at nascent planet forming systems to try and understand their water content. Do they have icy comets the way that our solar system does? What are the different ways solar systems acquire their water?” Chen said. “The question that we're all sort of edging toward is what is the potential for having habitable earths surrounding their stars and what life looks like there. Is it like ours or is it different?”

Levenson, likewise, hopes to utilize Webb to study the distribution of gas and dust around the active supermassive black holes at many galactic centers. However, she believes that Webb has a power far beyond the laboratory.

“We're asking some of the most fundamental questions of how did we get here? The history of the universe fundamentally leads into the history of people,” she said. “Whatever anyone's professional or academic focus, I think there's something to take out of scientific discovery, being able to appreciate it and the beauty of the observations.”

Robberto suggested that Webb can engage both astronomers and the general public.

“There’s a hope that the public remains fascinated and involved,” he said. “These are images that can capture the imagination and can help people understand the value of science, the value of understanding our universe, of truth, of how hard it is for certainty but how firm our knowledge is.”