Let’s be frank — Hopkins has yet to commit to the radical environmental action necessary to combat climate change, air pollution and toxicity. This lack of action directly contributes to the disproportionate harm that Black and low-income populations in Baltimore experience. Hopkins stands at a crossroads today: choose to remain complicit in environmental racism, or do its part to end it.

In an email to the Hopkins community in November, President Ronald J. Daniels announced a new Sustainability Plan meant to “articulate our collective vision for a healthy, equitable, and sustainable future.” In the Dec. 2 Sustainability Plan Town Hall, Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Sunil Kumar declared, “We need to discipline ourselves as a large organization and a key local partner with our community and the neighborhoods around us to act in a way that lives out what we tell our students and the rest of the world.”

Responses to question raised by leaders of the sustainability planning process during the recent Town Hall show the JHU community wants environmental justice, equity, and community engagement on a local scale. Screenshot during Zoom meeting.

What leaders of the sustainability planning process discussed, however, minimized sustainability to just climate action. Climate change is a serious global problem, and Hopkins, as an international leader in education and public health, has the imperative and responsibility to lessen its climate impact. But sustainability requires thinking beyond the climate crisis.

The University is a major polluter in the city, producing thousands of tons of waste each year.

What we throw out at Hopkins doesn’t just disappear. It’s incinerated, at the Wheelabrator BRESCO facility in South Baltimore, the largest source of air pollution in the city. Residents of South Baltimore suffer from high rates of respiratory and cardiac disease, which environmental justice activists correlate with the heavy pollution they face. The University has an obligation to address these concerns.

Town halls and bureaucratic committees alone won’t do anything to mitigate environmental harm. The University, simply put, must take responsibility for its pollution now; we cannot wait the years it will take to finalize the Sustainability Plan. Will Hopkins join Baltimore’s zero-waste movement? Or will it perpetuate environmental injustice by making more empty promises?

A community-led movement for waste alternatives

If it weren’t for the student activists of Free Your Voice at Benjamin Franklin High School in South Baltimore, city residents would be suffering from two massive trash incinerators, not just one. The youth leaders who stopped the construction of a second incinerator in Baltimore in 2016 went on to form the South Baltimore Community Land Trust (SBCLT), an organization working for “development without displacement” in the city.

SBCLT and Baltimore’s Zero-Waste Coalition have developed a Fair Development Plan for Zero Waste in Baltimore, laying a foundation for the city to shift from its “burn-and-bury” model of waste disposal toward compost, re-use and recycling infrastructures instead. Many city residents now consider incineration an unacceptable strategy for the city’s present and future.

Waste campaigners estimate that food waste and other organic materials make up 40% of the waste stream. Currently, Hopkins sends hundreds of tons of food waste each year to a facility 40 miles away in Prince George’s County, at great expense in cost and fuel. But a new state law in Maryland requires large institutions like ours to send their food waste to any available composting facility within 30 miles, if such a facility exists.

Movement organizers are petitioning the city and anchor institutions like ours to support the development of a local compost facility in Baltimore. The hundreds of tons of organic materials that the Wheelabrator incinerator burns every day could be diverted and instead instead in a facility that would support the local economy, create local jobs and restore local soil. We need to take this call seriously.

Hopkins students and faculty mobilize

Over the past few months, Hopkins students and faculty have been working together with SBCLT and the Zero Waste Coalition on this campaign to build support on campus and in the city more broadly for a community compost facility. To this end, we established a campus chapter of the Post-Landfill Action Network (PLAN), an inter-institutional network supporting students in mobilizing their universities toward zero-waste practices. We invite all students, faculty and staff interested in sustainable futures to join us.

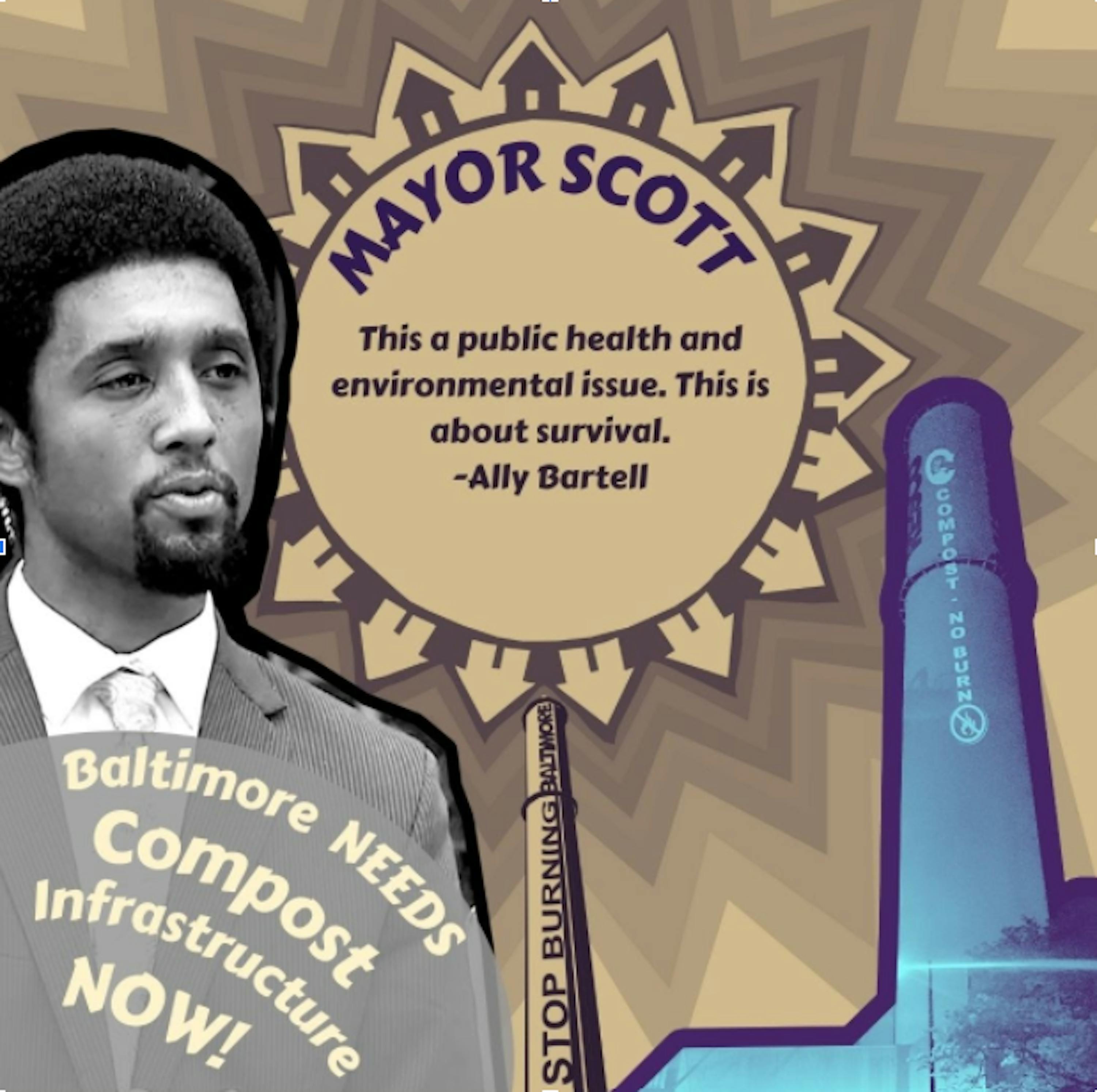

Amid increasing momentum for the zero-waste movement, both in the city and at Hopkins, University students and faculty took part in a public action at Baltimore’s City Hall in October, calling on Mayor Brandon Scott to develop a local compost facility in the city. Speakers made it clear that this strategy would be viable only with the support of major institutions like ours.

Hopkins community members (here, recent alum Ally Bartell ‘21) have been speaking up in support of Baltimore’s zero waste movement. Part of a recent series of advocacy graphics produced by the South Baltimore Community Land Trust.

At other local colleges like Towson University, students and faculty are mobilizing to encourage their institutions to pledge a minimum tonnage of organic waste to the community compost facility that is planned. Such pledges will ensure that the facility can operate at a viable scale. Like other institutional members of Baltimore Colleges and Universities for a Sustainable Environment, Hopkins needs to uphold its responsibility to all its constituents – University affiliates and Baltimore residents alike.

The University’s imperatives

As the largest employer in Baltimore and the leading public health academic institution, it is the University's responsibility to ensure a sustainable, equitable future for all. 70% of the University’s waste ends up in a landfill or incinerated, and the inadequacy of our current trash system means students struggle to properly dispose of their waste. From insufficient and overflowing bins, to inconsistent practices and sometimes inadequate signage, students can’t even take full advantage of the existing composting infrastructure.

It is hypocritical for a public health institution like Hopkins to ignore the effects of waste incineration in its own backyard.

Complacency is neglect. Neglect is violence. The University has a long history of exploitation in Baltimore, including medical racism and unethical research as well as gentrification. Hopkins is at a crossroads. This is an opportunity for the institution to truly serve its community and take real action rather than make empty promises.

A Baltimore-based compost facility would permit local institutions to divert compostable waste, save the money and fuel it takes to truck waste over long distances and support environmental justice in the city.

We, students and faculty at the University, have the power to insist that Hopkins commit to zero-waste infrastructure in Baltimore, alleviate pollution and tackle environmental racism and health disparities. We demand that Hopkins commit to sustainable waste infrastructure by pledging a minimum tonnage of waste to the local composting facility envisioned by the community-led, zero-waste movement in the city.

Hopkins cannot stand in the way of community organizers and their years of hard work. Baltimore desires and deserves a zero-waste future. Will Hopkins continue to greenwash and disappoint, or will it support the vision for local waste alternatives and turn its performative commitment to sustainability into meaningful action now?

Bürge Abiral is a doctoral candidate in Anthropology. She is writing her dissertation on the ecological food movement in Turkey.

Laís Santoro is a junior studying Public Health and Environmental Studies from Pennsylvania. She is an executive member of Real Food Hopkins and a Community Impact Internships Program Intern at Whitelock Community Farm.

Junior Environmental Studies major Alex Noel contributed to this article.

All three authors are part of the 2021-22 Sustainable Design Practicum's year-long collaboration with the SBCLT and members of the new PLAN chapter at Hopkins.