Health-care disparities and vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. have been brought to the forefront of national conversation in light of the pandemic and the resurgence of Black Lives Matter.

However, without understanding how “Blackness” became medically recognized, these phenomena are difficult to understand.

Dr. Rana Hogarth, a historian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who also holds a MPH from the Bloomberg School of Public Health, specializes in the medical and scientific constructions of race.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Hogarth discussed how early European anatomists displayed an interest in dissecting dark skin, pointing to this as a contributing factor of later constructions of race. While science aspires to objectivity, Hogarth said, scientists would never reach this goal while studying environments where Black people were artificially forced into certain social positions, such as the Atlantic slave trade.

One example of the way these social roles impacted research and medical practice lies in the work of John Lining, an 18th century physician best known for his work, “A Description of the American Yellow Fever, which Prevailed at Charleston, in South Carolina, in the Year 1748.”

“John Lining was a physician in South Carolina who would have had lots of contact with Black people. When he says there’s something about the ‘constitution of Negroes’ that makes them not liable to this fever, he also says that he thinks that Black and white people can get another kind of fever, that they’re equally as liable,” Hogarth said. “He clearly had his own prejudices, he lived in a slave society, he was a slaveowner by marriage. But he made this observation at a time when slavery is thriving.”

In her 2008 book Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora, Stephanie Smallwood, an associate professor of history at the University of Washington, chronicles how those who traded enslaved people performed a “rationalized science of human deprivation,” seeking to determine “the limits up to which it is possible to discipline the [Black] body without extinguishing the life within.”

According to a 2020 meta-analysis spanning two decades, Black patients are 22% less likely than white ones to receive pain medication. Racist misconceptions about pain tolerance used to justify slavery are still believed by physicians today.

A history of race-based research

Dr. Durryle Brooks, a researcher at the School of Public Health and an anti-racism consultant, pointed out that power structures often lead to false narratives, like those spread about the University’s founder Johns Hopkins, an enslaver who was until recently thought to be to be an abolitionist.

“People tell selective truth because they have money to influence and power to sort of create a master narrative that everybody has to adopt,” he said. “We always have counter narratives going, but the ones that rise to the top are usually the ones that are fueled by money and access and privilege and power.”

Stories of medical mistreatment, race-based medicine and race correction are realities today, Hogarth explained, pointing to the example of sickle cell anemia, an inherited blood cell disorder that in the U.S. primarily affects Black people. Last fall, a Black man with sickle cell told The News-Letter that he believes that he was intentionally sterilized by doctors at Hopkins Hospital.

In the 1970s, the government passed the Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, which implemented laws mandating testing for Black people and calls for selective abortion.

“How many medical students in the ‘60s or ‘70s were saying, ‘Sickle cell anemia is a molecular inherited disorder that has more to do with your genetic and geographical ancestry than your race’? People were saying, ‘Sickle cell anemia is a Black disease.’ It has been built into both lay perceptions of health and disease and disparity, and also within medical practice,” she said.

The Human Genome Project, which was completed in 2003, was a major advancement in our understanding of genetics. With the human genome sequenced, scientists gained a new understanding of how human beings were related. However, this new information did not stop doctors from making assumptions about Blackness.

“There was all this great hope around the Human Genome Project,” Hogarth said. “Instead of having the moment of, ‘Oh, we should stop making these assumptions or having this messaging about racial difference.’ What people started to do instead was to say, ‘I don’t see color. I can’t be racist.’”

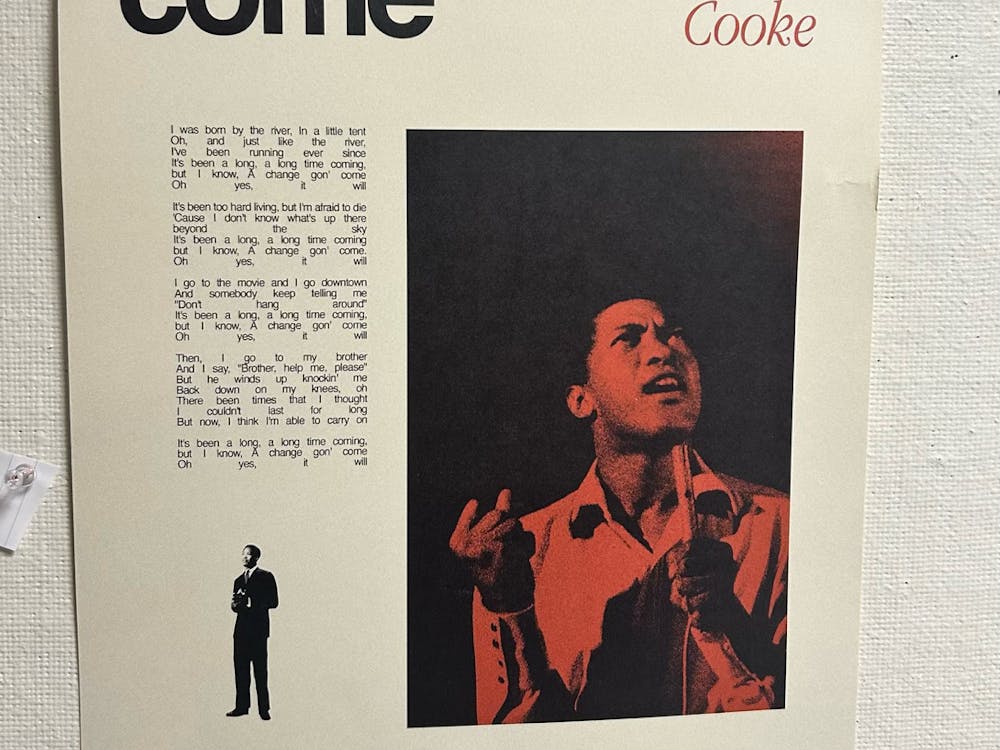

COURTESY OF RUDY MALCOM

All of these instances of mistreatment and bias have created the modern landscape of medicine. Brooks pointed out that while most Americans understand well-known instances of mistreatment, such as the 40-year, ethically abusive Tuskegee Syphilis Study, distrust is fueled by far more experiences.

“From my perspective, folks are still thinking that the conversation around medical mistrust is all based in Tuskegee and those trials, which were terribly racist,” he said. “But the reality is that it’s actually much more nuanced, and it’s contemporary. It’s so every single time you go to a doctor, and you have poor quality of care there, that breeds medical mistrust or distrust, specifically with that institution.”

On the Hospital’s website, underneath a description of HeLa cells, there is a brief explanation of the school’s participation in the theft of Henrietta Lacks’ cells, another well-known example of medical mistreatment toward Black people in the 1950s.

The page first explains that Hopkins was one of few leading medical institutions to agree to care for Black Americans and then goes on to describe the segregated conditions where, “racial discrimination was often unacceptably a part of day-to-day interaction.”

The following page includes a list of changes spurred by the ethical disaster, including requiring informed consent and institutional review board oversight; ensuring that patients were able to view their medical records; and abolishing segregated wards.

Interestingly, despite the daily racism alluded to in the previous tab and the framed ‘win’ of desegregation, the Hospital insists that it provided “the same quality of care to both black and white patients.”

Regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, Hogarth pointed out that messaging is a crucial driver of a lack of trust of the medical community.

“[Let’s] go back to the idea of ‘Oh, we learned our lesson, everybody’s the same; there’s no biological basis for race,’” she said. “If you have something on the FDA website that says that it’s going to act differently in your body — and assumes that because of your race — you have a messaging problem. What message am I supposed to believe — when the government claims to be doing beneficial research or when they claim to say race doesn’t matter?”

Hogarth drew parallels between this kind of messaging and the Tuskegee experiments.

“The study was premised on the idea that syphilis was going to be a different disease in Black people than white people,” she said. “The underlying assumption was that their bodies are different. That is why they did this crazy thing.”

The role of medical school in enacting change

Hogarth believes that while medical schools must change the way they discuss race in order to improve patient care, the current system leaves little room for these discussions.

“You’re going to have to tell medical students that they need to start questioning all of these things that they take for granted. The approach to medical school is learn everything, memorize everything. I have to get to the point. I don’t have time to ponder the early origins of racist assumptions about lung capacity,” she said. “We need to consider, for example, the way in which we just continue to be lazy in how we use race and innate biological difference. I think that it’s almost like a shorthand for some of these social ills.”

Prioritizing natural sciences over social sciences, Brooks argued, doesn’t seem to be doing any favors for advancing the anti-racist, trust-building goals of large medical institutions like Hopkins.

“Hospitals are complicated systems,” he said. “What gets hard is there’s a disconnect between what research is deemed more important than others. The social scientists don’t live well with the STEM folks for some reason.”

Today, the Hospital devotes far more resources toward regaining trust from Black Baltimoreans. However, many of these interventions do not address educating medical students on racial bias before they begin practicing.

Given the University’s history, and the near constant documentation of care disparities, such as in COVID-19 units and maternity wards, it is evident that these steps are just the beginning of correcting the racist legacy of medical institutions.

COURTESY OF KATY WILNER