Tom Connor was a Features reporter for The News-Letter from 1974-75. He is Creative Director/Chief Operating Officer at Weinrib & Connor, Inc., a full-service advertising and marketing agency.

The News-Letter: Why did you first decide to join The News-Letter?

Tom Connor: I came on board in ‘74-‘75. I had written a Letter to the Editor. And I was very concerned at that time that there were few people on campus who were devoted humanities scholars. It wasn’t a question so much of selling out but a preoccupation with careerism. The editor Russ Smith said, “This letter is pretty good — you ever think about writing for us?” Man, I gotta do a senior thesis; I have three jobs because I live large. But at the same time, I had made it my ambition to read The New Yorker every Friday afternoon. So I’m thinking, “If I have time to read The New Yorker, how long is it going to take to do a feature story?”

And this is the God’s honest truth; I had just read Hunter Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas at the recommendation of a med school student who went to the same high school as me. We ran into each other on campus — one of the more bizarre serendipitous moments of my life — and he says to me, “Have you read Dr. Thompson?” I go, “You’re a physician; I couldn’t get a 1 on the AP test. How can you expect me to follow?” Now it’s the ‘70s, okay? I lived in the Beta house. Right next door was Phi Gamma Delta, which was the jock house where the All-American lacrosse players lived. So, if I’m going to become a Features writer, I’ll just do like Dr. Hunter Thompson, and lo and behold that’s what happened.

Forget grad school — there’s no fellowships, there’s no jobs. And boy, that’s a nice thing to find out. And then, you know, it wasn’t like I didn’t continue to focus on my studies. Quite the contrary! I thought maybe it would be good psychic income to try writing for the school paper. I had artistic talent that I was born with. So it wasn’t so much a question of how much time this is going to take; it was more of a true creative process, and I was pretty much a Hunter Thompson manqué endeavoring to bring some outside-Homewood storylines to campus.

N-L: What are some of your best or funniest personal stories from your time at The News-Letter?

TC: Well, again, this is the ‘70s. This is not to say that everybody was under the haze of weed, but I think the only guy who didn’t smoke dope in those days was Bill Clinton.

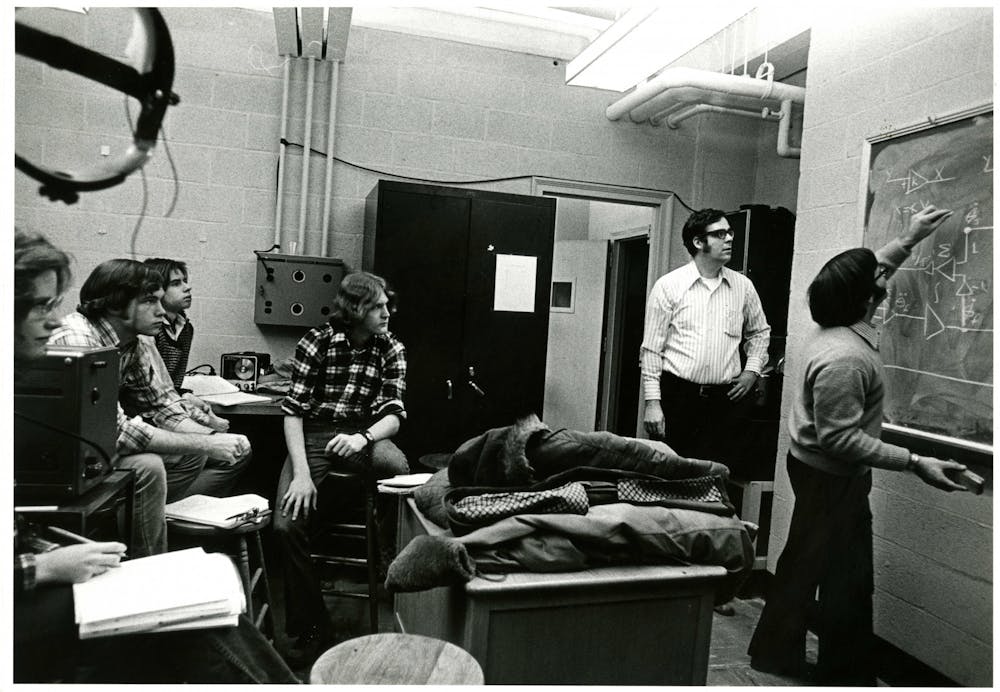

In the Gatehouse, there was an attic, and you had to get up there by a ladder. There might even have been a rope that you could come down. Now this could be apocryphal; I don’t do ladders and ropes up to a higher level. I want architecture. That was because I didn’t have a car; I had a bike. If I hurt myself, I wasn’t getting around. So that’s one thing. The second thing is I don’t think there was any indoor plumbing, so forget about washing your hands if you had too much newsprint on them.

N-L: What were some of your favorite articles that you wrote?

TC: The one about the underground papers in Baltimore was the best because here I am working for an underground paper, The News-Letter, and there was one paper called The Owl. I remember meeting the editor-in-chief, and he looked like an owl.

N-L: How did The News-Letter impact your life as a college student? Why was it important to you?

TC: I’m on the creative side of advertising, and I can come up with a line in a conversation with a client; I can come up with an idea for a commercial with banter. That’s the inspiration; the perspiration comes in in the vetting of it, and the actual going from spark to fire and the fuel you add to it is the discipline — being able to sit down for an hour or whatever and crank it out.

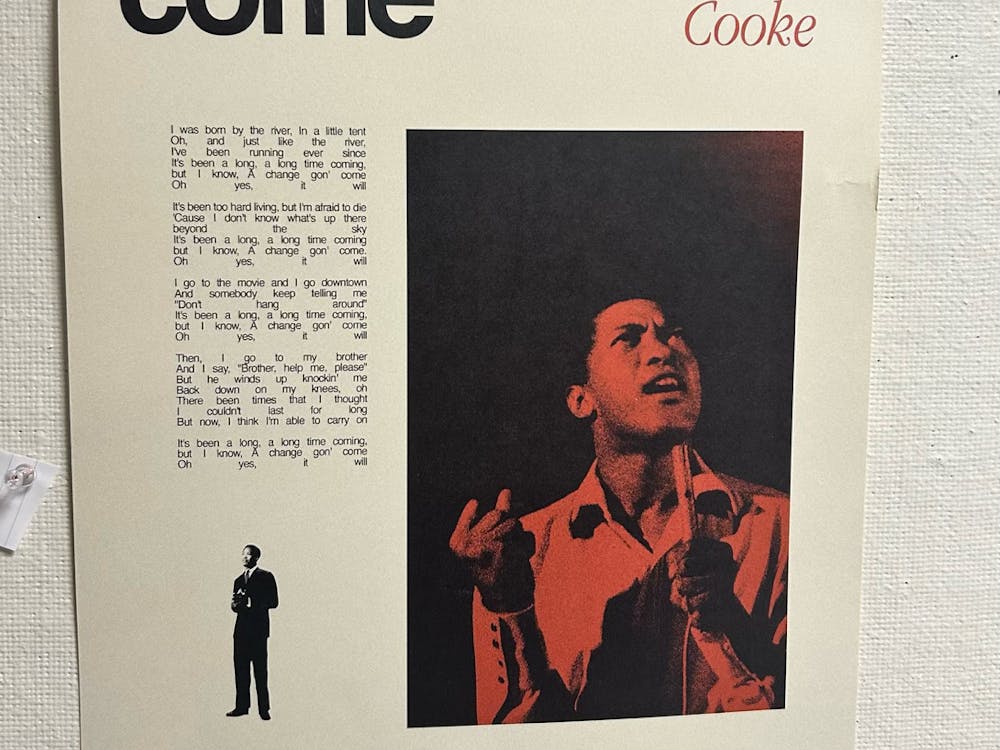

Russ Smith said, “Hey, why don’t you write about Bob Dylan’s new album?” I said, “Hey, Russ, I never did a review before.” He says, “You wrote about the Grateful Dead’s ‘Ship of Fools’ in your first letter to the editor.” And you realize reading other people’s copy that this isn’t so impossible to do. This idea that you’re empowered is really important. Not too many places will grant you unfettered thinking, process and authorship and all that.

But empowerment, even if it’s restricted, is so important to your personal energy — you gotta crank it out. And once you get into something that you’re really passionate or you feel great about — and creative writing and journalism should be all that — then you can start to put up with whatever the strictures and guidelines might be, but more importantly, you’ll sail past them or sail through them or alongside and on-board them and do a terrific job because your focus is there. Now, does writing features for a college newspaper do all that? I think so.

It gave me a voice when it sounded like my voice would be drowned because I couldn’t go to grad school. I certainly understood that it was my Hopkins degree that made me a writer, but it was The News-Letter that gave me freedom of expression. What The News-Letter gave me was a chance to see how, under the auspices of the discipline of journalism, one could be very creative, by just following the rules of being a good journalist. It was a chance to pretend I was outside of school, in a career.

N-L: How do you remember The News-Letter impacting the greater student body at Hopkins?

TC: Hopkins back then had a pretty good composite student body of women and minorities; it was very diverse except when it came to the subject of major. A lot of people were pre-meds — good people, but they stuck to their knitting. Those poor bastards had to follow a very rigorous study platform; their curriculum didn’t allow for the expansive thinking that humanists, so to speak, would follow.

The News-Letter was the newsprint of what people were living. It’s a lot different than today; storylines weren’t as highly charged with, if you will, a philosophical or social conviction. Our social conviction in the ‘70s was, “Screw this.” Most people from back then came out of school and hit the real world and realized, “Holy shit, where was I?” It was kind of like “Rip Van Winkle.”

If you found stories from the ‘70s, you would see, in the early ‘70s especially, definitely more politicization. And when I graduated in ‘75, there was less. We were interested in getting rid of Dick Nixon, that’s for sure, but when he left, nobody gave much thought to President Ford.

When the papers would be delivered on campus, people would grab them; it was like right out of the movies when you see “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” By all accounts it was a very substantive effort on behalf of extracurricular investment of time by students who also had the typical Hopkins academic pressures. So I think that was pretty cool and hard to fathom an internet free world. But you knew people read it, and certainly people talked about. I don’t know that publications enjoy that benefit today.

N-L: How did your time at The News-Letter help prepare you for your career after college? What did you learn at The News-Letter?

TC: Writing stories for a deadline is a daunting task, but you can break it down to the discipline of how you manage your time. Thanks to The News-Letter, I never develop writer’s block because it just doesn’t make any sense. Getting into the routine of following your deadlines and organizing your content — I don’t know how you can teach this practical experience.