Professor Richard Rose began his education at Hopkins in September 1951 and graduated in June 1953. In his two years as a student, he wrote news stories and features for The News-Letter. He currently lives in England and boasts 4,000 books in his library at home.

The News-Letter: When did you work at The News-Letter, what was your position and why did you decide to join?

Richard Rose: I entered Hopkins 70 years ago when life was very different. I’d already had a lot of experience in high school. Not only had I edited the high school paper and the yearbook, but I had also worked at print shops. I always wanted to be a newspaper reporter, so I went out for The News-Letter. As soon as I got there, I was one of the small group that was set on a newspaper career, whereas there were pre-meds who wanted a change from cutting up frogs and things like that.

My first year, I just wrote news stories. My second year, I was relatively senior as a reporter so I tended to write what might be called news features. I once wrote a review of a play done by the drama society. They didn’t like it, so I stopped doing that. I was going to be Managing Editor in my third year, but instead I got my degree in two years and went off to London.

N-L: Do you have any particularly memorable stories from The News-Letter?

RR: There were two stories I’m proud of writing. One of them was my first week at Hopkins, I got hold of the yellow pages of the phone book, looked up newspapers and rang up every English language paper. I got to United Press International, and they said I could be a stringer for them. I got a press card, and I got a felt hat to make myself look older. I ended up cutting a class in constitutional law to cover a murder trial because it was a national murder trial in Baltimore then. A man named G. Edward Grammer had killed his wife and tried to make it look like a car accident. He went to the electric chair. I wrote it up for The News-Letter.

The second thing was more interesting and more relevant, a historical document if you like. I don’t know what Hopkins is like nowadays, but I went there because, like the University of Chicago, they gave you a degree for what you knew rather than for many hours you sat on your backside in class or how many credits you accumulated. It was called the New Plan. The idea was that if you were going to get a doctorate, a real doctorate, a PhD, the sooner you got rid of your B.A., the better. I wrote a series of stories about how the New Plan was working out to recruit students.

One of my fellow undergraduates had served in the Israeli army in the War of Independence of 1948. He had an education which wasn’t based on books. I interviewed senior officers of the University about how the plan was working out. The plan was abandoned, but the stories are on the record of what the New Plan was about, and I’m very much in favor of people getting degrees on the basis of what they know rather than accumulating numerical points and ticking boxes.

N-L: What were your writing experiences at Hopkins like?

When I was in the department for Writing, Speech and Drama, it was unusual. Writing was a code word for literature rather than journalism.

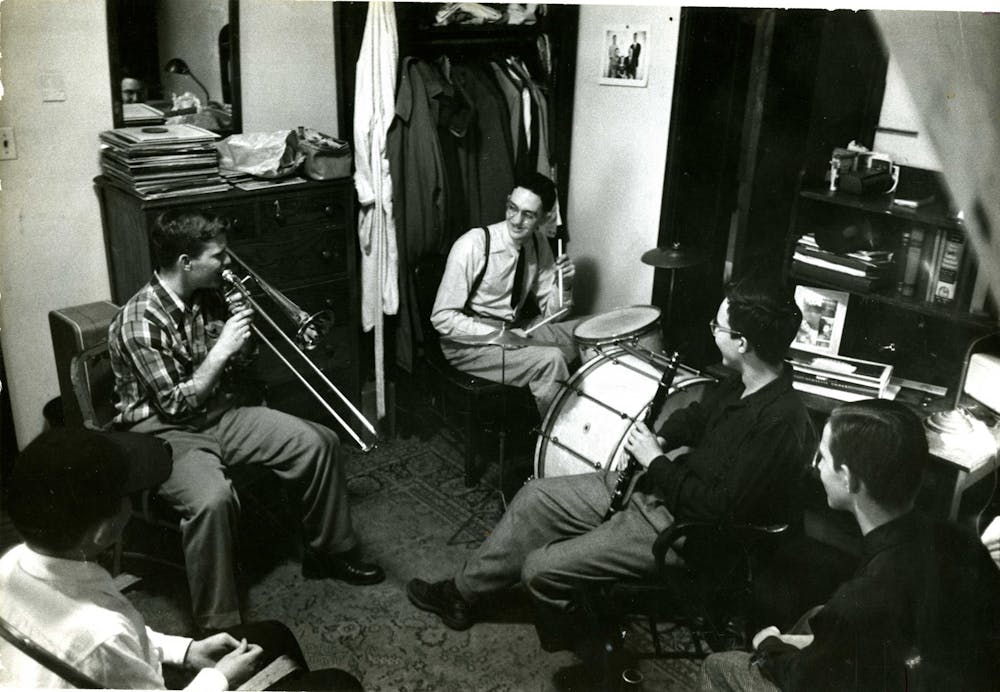

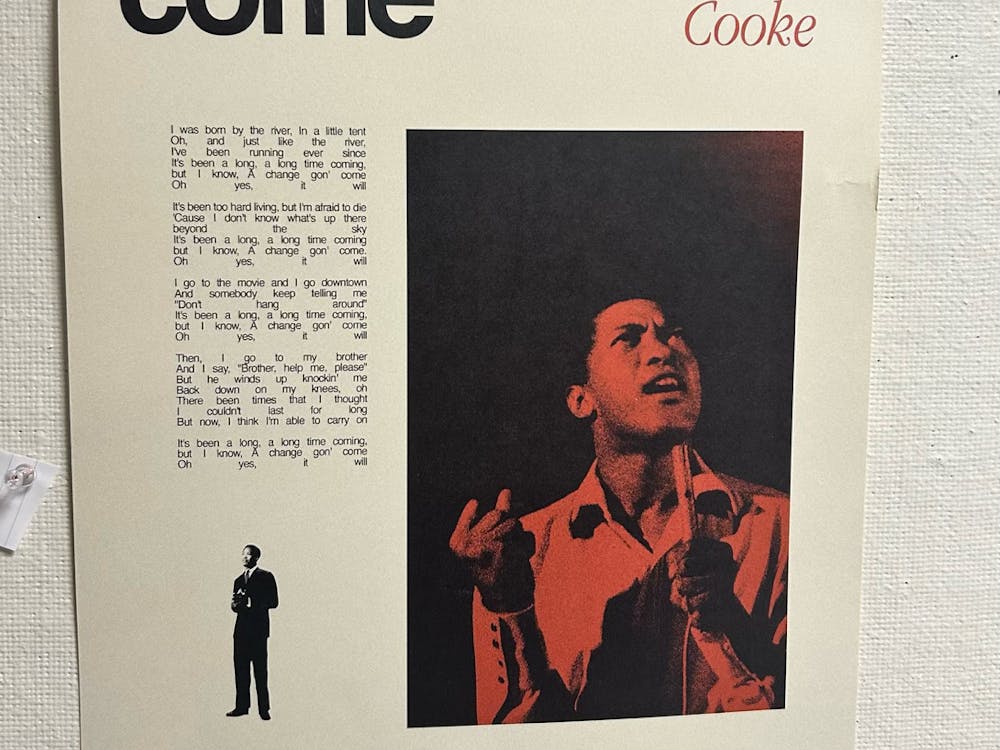

As I understand it, now as an undergraduate in writing, you can get a degree writing poetry or short stories. In my day, I wrote a double dissertation comparing Proust and Thomas Wolfe’s idea of time and another on the evolution of worldviews between T.S. Eliot and jazz musicians. It was really a comparative literature department. Reading was the way to learn how to write. You have to experience things. Being interested in jazz and hanging out in places you don’t tell your parents about when you’re in secondary school and covering murder trials is part of one’s education.

Newspapers are about the world around you, and I wanted to nail that. My doctorate is in social science, rather than literature. I had this mixture of being interested in the world that you read about in the newspapers and being interested in the world that you read about in T.S. Eliot’s poetry, Proust or Faulkner. I never wanted to write a novel, but I wanted to write well... The News-Letter, and writing for a weekly newspaper, teaches you how to find out information, where to go, how to write to fit a space and how to write to meet a deadline. It’s a good discipline.

In my day, The News-Letter was printed on a metal type, and the metal type was put in a heavy iron casing — chase it’s called. By God, you couldn’t cheat, you couldn’t lengthen it, it had to fit the space.

N-L: Could you talk more about what The News-Letter was like?

RR: First of all, it was a friendly place. They welcomed people. You’ve got to remember that there were only 300 freshmen, 1,100 undergraduates on campus. Some of them were in engineering, and others were concentrated on pre-med. It was a friendly place and it was a good mixture of people who were doing different subjects. I was in the humanities and other people in my dormitory were doing engineering or pre-med, but we were quite separated in some ways. But we had a common interest in The News-Letter as you might if you’d been in the music or drama society.

Secondly, it was small. I don’t know how many people would contribute two or more stories a month — I was probably one of them. I’d go down to the paper when it was being made up to make sure everything fitted, on the edge of East Baltimore. It was the only extracurricular activity I was involved in.

The editor, Frank Somerville, ended up being editor of the Sun, and Al Epstein was a professor of medicine at [the University of Pennsylvania] and Ross Jones ended up being one of the officers of Hopkins.

The campus was a funny place. There was a large number of Baltimore boys because it was a local university. There were the state of Maryland engineers and a small number of humanities students. The News-Letter was where you mixed with people.

N-L: Why was the News-Letter important to you?

RR: Because it got me out of the library and it got me to mix with other students. [It was part of] the world of learning and scholarship... [School] was a tentpole of learning rather than a social occasion, and The News-Letter was the exception.

N-L: How would you describe what Hopkins was like when you were there?

RR: The right place for me. A bit old-fashioned. It had a nice campus in a big city, and you could get downtown fast. It was a very pleasant place with an enormous amount to respect. It was a world of scholars, of people who were very learned, who knew a lot: about America, about what you could learn from literature, literature written in different worlds like Mississippi and Asheville, N.C. and wherever Hemingway and Kafka wrote about. There was just an awful lot you didn’t know that you could learn there.

N-L: Is there anything else you wanted to share about The News-Letter?

RR: I would certainly encourage anyone who is going to college to go out for the student newspaper. You’ll learn a lot. Words are important. Writing is important. You get a combination of getting ease and speed of writing and clarity on a weekly newspaper. Being at a great university in a big city in America like Baltimore is a 24/7 education. Make the most of it.

N-L: What would you say to current Hopkins students reading this interview? Is there anything you would want them to reflect on given your experiences?

RR: If you want to do something, don’t talk about it. Try doing it. Don’t be afraid to venture, but respect other people whether they’ve got PhDs or dropped out of high school.

Try and see things from more than one perspective. Educate yourself; only you can do it. Hopkins can give you a degree, but only you can put together what you’ve learned. And it will take time — be patient. When I was 21, my ambition in life was to write a book. Since COVID-19 started, I’ve started and sent one book off to the publisher, and I’m now into my second book. Depending on what you mean by book, I’ve written about 50.

When you’re young, you’ve got time to explore and experience. Don’t just do what other people do because they’re doing it. Have some sense of what you, as an individual, want to do. If it looks unusual to other people, that’s their problem.