Eric Garland was a writer and editor for The News-Letter during his sophomore year and Editor-in-Chief as a junior. He graduated in 1978 and joined the City Paper startup. He went on to work on a number of magazines, and since 2009 has been a partner in Blue Heron Research Partners, a journalistic-driven due diligence firm for hedge funds and private equity firms.

The News-Letter: What did you study at Hopkins?

Eric Garland: I was a traditional English major, and I wasn’t going to go to grad school. So what do you do with an English degree? Well, that means you can think, write and analyze, and that lends itself to journalism. What was so attractive about The News-Letter is that there’s no faculty oversight. It’s up to the students who were there to create it.

I don’t want to dissuade anybody that’s brave enough to want to go into journalism. But it just, frankly, is an uphill climb. But it’s needed. It’s vital.

I always felt that Hopkins actually was a better place to learn journalism, because you really get to do it on your own. No supervision. You make a lot of mistakes, and you learn from your mistakes. So maybe we’ve made more mistakes than we would have with adults in the room, but fine. It’s always up to you to create it. So I really value that. And in a way, I think that helped me and some of the others that came out of The News-Letter.

N-L: Why did you join The News-Letter?

EG: I was always a reader. I was a paperboy growing up. I lived in Pittsburgh and so I delivered the morning paper. And actually, I was a terrible paperboy. First, I don’t like to get up early. So it was tough to wake up at 6:30 a.m. And then, second, I was even worse, because I was so interested in the newspaper, I would get the stack of papers that I was supposed to walk my route and deliver. And I would just sit down and start reading the paper on the curb.

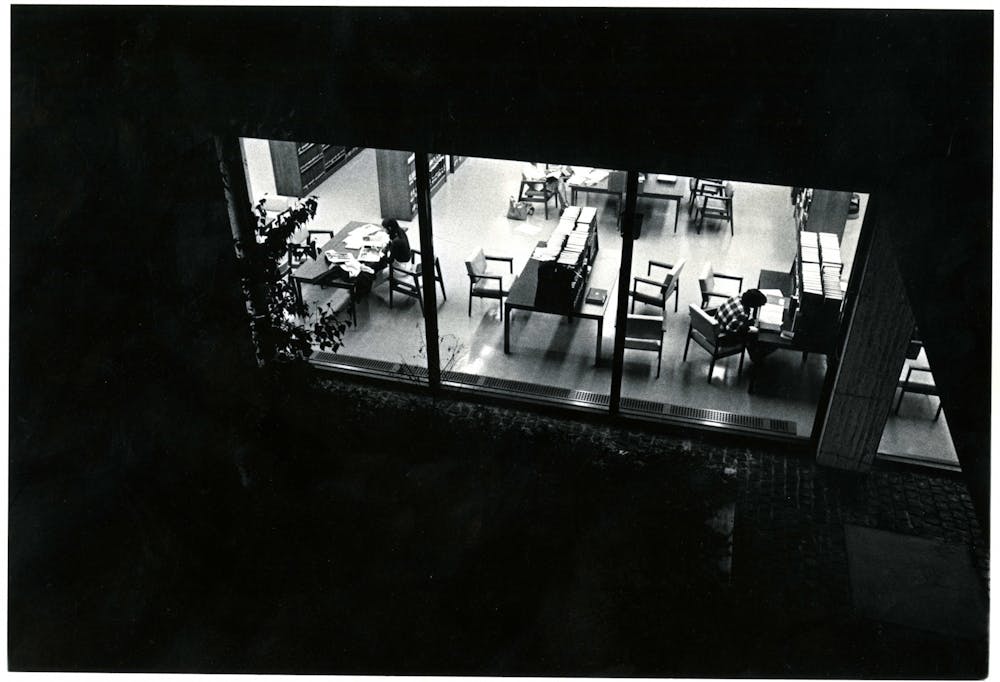

You know, I was terrible as a delivery boy, but it got in my blood that I loved reading the paper and could sort of see how it was put together. And then coming to Hopkins, in the mid ‘70s, there’s a lot of politics in the air. Watergate, and lots of great journalism being done. So it was a real conducive era to sort of be inspired to try to do journalism. And then I think starting in the fall of my sophomore year I just went into the Gatehouse. And there were a bunch of slightly oddball eccentric characters hanging out, banging away on typewriters, smoking cigarettes, drinking open bottles of liquor.

N-L: What did you do after you graduated from Hopkins?

EG: I did continue in journalism and that was most of my career, but I’ll bring you up to speed. I stayed in Baltimore. There were several people that were there in the ‘70s and out of that group emerged the founding of the City Paper, which was an alternative weekly paper in Baltimore.

Russ Smith was one of the founders and had been editor at The News-Letter before me. Russ graduated in ‘77 and had started the paper after graduating. I graduated in the spring of ‘78 and joined. City Paper was meant to be an upstart. Baltimore, believe it or not, had three daily newspapers at the time. The Morning Sun, The Evening Sun and The News-American.

We felt there was a need and an audience for an alternative paper. And so that was started. I stayed there for just about a year, but City Paper went on. From City Paper, I then went on to Baltimore magazine, which is the monthly city magazine, and I was a senior writer there. I was at Baltimore magazine for several years and developed an interest in covering business, which I felt was not being looked at in-depth by the daily papers in Baltimore. So there was a lot of room to write and do long-form journalism about business in Baltimore.

After a few years there, that caught the attention of a local publisher named Edwin Warfield. So I joined a very small daily legal newspaper in Baltimore called the Daily Record in the mid ‘80s, and we came up with the idea to do a monthly business magazine for Baltimore. Believe it or not, Baltimore still had a fairly vibrant business community. Not so much the older, declining, steel companies and auto plants, but more focused on banking and finance and law firms. And then emerging developments at that time in not really tech, but biotech and health care, real estate development and so on.

So, we created a monthly magazine that did very well. And I ran that for about five years in Baltimore. Eventually, the magazine wound down, but I enjoyed being in Baltimore. But I never went to work for the daily papers — that wasn’t my thing.

And then I sort of ran out of journalism to do in Baltimore, moved to New York in ‘91 and became a senior editor at Adweek magazine and had a good run there. Lots of great stories to write and cover, though no shortage of egos and personalities, conflict and drama in advertising.

A lot of people at Hopkins in the ‘70s that were attracted to The News-Letter, we were inspired by both the journalism of the time, which certainly was in the mode of [Bob] Woodward and [Carl] Bernstein covering Watergate. And the ‘70s was like a golden age for investigative journalism.

Then in the late ‘90s, I raised some money and launched a national magazine called Dads. At the time, I was a young father, and looked around and saw that the dominant magazines that were once called Parents and another called Parenting, but they were all aimed at women, which made sense, because that was the traditional role in parenting. And I felt there was a need to have a magazine that spoke to the men, to the fathers.

And so again, I raised some money from investors. And we started, unfortunately, at a bad time. We raised the money and launched in early 2000, just in time for the dot-com bubble to burst, which effectively wiped out any possibility to get financing for any kind of new venture, particularly a print magazine, but we put out four issues that I thought were terrific issues and got a lot of interest.

So I did a startup that didn't work. But I learned a lot about running a business, which has come to help me a lot. I then went and did one more journalism as editor of a financial magazine, a trade publication called Financial Planning, which goes to independent investment advisors. And I did that for a few years, just learned a lot. That company was bought by a private equity fund.

And again, this is now the mid 2000s, and I could just see the handwriting on the wall, that magazine journalism, newspaper journalism was up against it. I mean, I love journalism. And I love doing print journalism. But it just was bleak and then looking like a dead end. And having to work as an editor and head of a magazine, having to continually cut the budget and cut staff, being asked to do more with less resources just was not an attractive prospect.

Around 2006, before the financial crisis, I talked to some hedge fund guys, and they saw what [my friend] was doing at Fortune and said that kind of investigative journalism could apply very well to the qualitative research that they needed to do on companies and management teams and investments they were making. I joined them about a year after that we got through the financial crisis.

And ever since then, it’s been onward and upward. It’s called Blue Heron Research Partners. We're probably the biggest one of its kind. Now we have 75 employees, about half in the New York office and half in London, other people globally that work for us, and we do it, but it’s still very much driven as journalistically driven research on behalf of hedge funds and private equity. So it’s very much in the mode of what I’ve been attracted to and interested in in journalism all along. The good thing is, we have clients who can pay us.

N-L: Are there any traditions you remember from your time at the paper?

EG: I’ve already told you about the smoking. I certainly remember many late nights between the basement and then the other part. As you know, there’s that little alcove at the very top. You have to get up by a ladder. I think we had a mattress up there, and you would go up there and sleep if you had to overnight. But that was kind of a hangout.