Caleb Deschanel was a Managing Editor from 1964-65 and an Editor-in-Chief 1965-66. He is a cinematographer and film director who has been nominated for six Academy Awards.

Jim Freedman was a Features Editor 1964-65 and an Editor-in-Chief 1965-66. He is a professor, author and founder of an international consulting firm.

The News-Letter: What was your experience of working in journalism in Baltimore?

Jim Freedman: Remember that journalism was a bit of a different thing in those days. I mean, it was more noble, in the sense that we were the gutsy soul of the society.

It was kind of a bizarre, interesting thing to do. But we were anathema to the administration.

Caleb Deschanel: We got called on the carpet weekly. By [University President Milton S.] Eisenhower’s henchmen.

JF: We were real bad. I remember one time that we decided that we didn’t have a good lead. So we just made something up, and just had these massive headlines about something that never even happened. We had a wonderful, wonderful time with it.

CD: We were a weekly newspaper at that time, it was not a daily. So probably a little less pressure, although it always seemed like we were working on it all the time, even though it was a weekly. So I don’t know what it’s like when it becomes a daily, except we did run a daily.

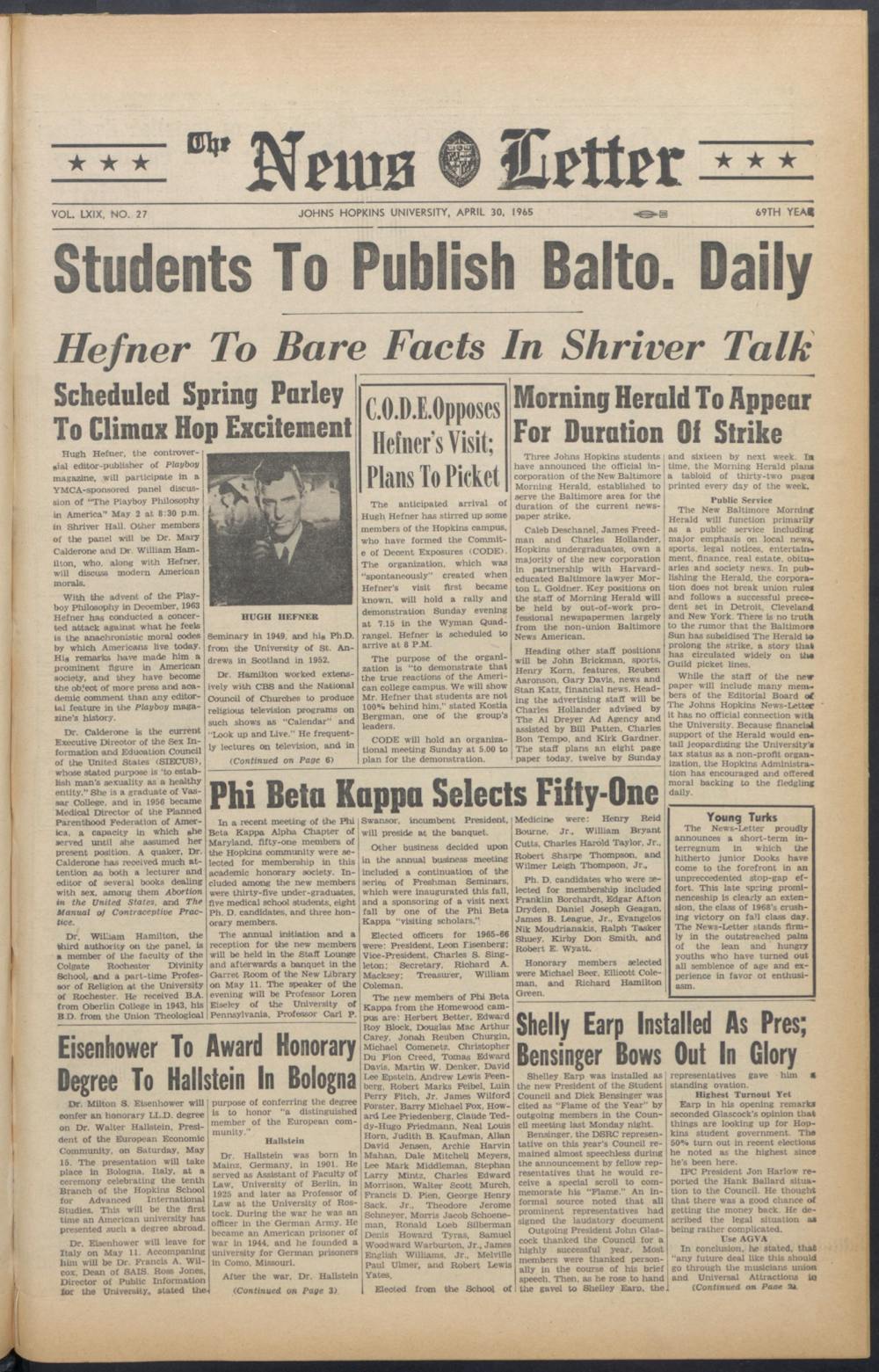

[CD is referring to The New Baltimore Morning Herald, a daily paper that he and JF ran April-May 1965.]

JF: We ran it, it was a bigger operation. We had to set it in hot type. And Caleb did that.

CD: What happened is that there was a strike of the Baltimore Sun. And there was the other newspaper, which was the News-American. The News-American, for some reason, decided to shut out their workers when the Sun went on strike. I’m sure it was some kind of canoodling between the two papers to eliminate all newspapers at the time, so that they can sort of fight the union.

You know in Citizen Kane, where Kane says, “I thought it’d be fun to run a newspaper.” It was kind of what we thought. I think we’d just become full editors, we’d just been voted in as the editors of [The News-Letter]. And then we go running off to do this newspaper.

We literally stole all the typewriters from The News-Letter, and we brought them to this apartment. We literally took over the building. It was filled with people. We put in big tables with three or four typewriters at each table and had people on, got phones and everything.

It was financed by Jim and me. Jim had some money that he had from the car accident when the insurance company paid you. And my mother had put aside money for me to go to graduate school, and she put it in a savings account in my name. I just was taking money out of that to use for the paper, thinking that we would get it back from advertising and everything. What happened was, the bank had an arrangement with my mother that if I took any money out, they would tell her. So I immediately get a phone call from my mother, like, “What the hell are you doing with that money?” And I go, “Oh, what do you mean, how do you know about that?” So that was a little worrisome for a while.

JF: This was between April 30 and May 15. This was a daily paper with 40 to 50,000 circulation.

CD: All our national and international news was based on tips from the parents or based on watching the news on TV and listening to it on the radio, and then just having our reporters reconfigure it in their own way, and creating our own byline.

CD: There was a faction of people in [The News-Letter] who wanted to kick us out and wanted to take over the newspaper. They were upset that even though we were the editors of The News-Letter, we had kind of shirked our responsibilities to go run off and run this daily for a couple of weeks.

It really was the town crier. It really was the way people would get information, aside from listening to their neighbors, or the radio to some extent.

N-L: Why did you first decide to join The News-Letter?

JF: I had always wanted to be a journalist or something like that. It went back quite a long time. Particularly international stuff fascinated me.

This was just at the end of the McCarthy days. One of the most extraordinary characters was a prof that I had at Hopkins as a freshman. His name is Owen Lattimore, and he had been attacked by McCarthy. He was an extraordinary character who had roamed the Mongolian, northern China and had written some extraordinary things.

By that time, I was a freshman. And by that time, I kind of resolved that that’s what I wanted to do, was to spend my time in conflict areas internationally. The best way of getting into it was through journalism.

CD: I got involved because early on, when I was a freshman, I met a couple of people who were involved with The News-Letter. I’d gone to school and been on the newspaper there. I really liked it. I liked the idea of investigations and discoveries of things. That’s what really got me involved was because I never really even thought about it.

Ours was a tabloid [size] like the New York Post or the Daily News. In order to sort of play around with it, we’d sometimes turn it on its side, so it looked like the New York Times or something.

The other thing that I really loved doing is writing headlines. We would always have fun, liberating and doing all sorts of strange things with the headlines.

JF: The paper was phenomenal to look at. Caleb was doing amazing things.

N-L: Did your work for the paper help you and your career later on?

CD: Everything you do in life that you’re really inspired by and that that motivates you is all based on what excites you and the curiosity that builds in you. That’s the thing about the news, running the newspaper, was the curiosity.

There are parts of me that are ashamed of some of the things we did, but at the same time, you couldn't fail, you couldn’t not put out the newspaper, you couldn’t not get it in that day, because you said that you were going to publish six days a week, or whatever it was.

That was kind of good training for going into the field that I went into. There’s some things in life where you just can’t fail at that. I mean, just, there's no excuse. It’s like in the movie business, you can’t ever quit.

All newspapers have deadlines. And there’s something great about that. To this day, I still feel it. I mean, in everything that I do there’s a deadline, and you can never fail. You may put out something substandard, but you’re going to put it out, and it’s going to be there. Hopefully, if you’re lucky, it’ll be great. And it will be good and valuable for people who read it.

JF: I think trying to figure out why conflict exists and why it starts and why it’s possessed in certain very complex political situations is very different; I found a great difficulty. One of the best ways to figure it out is to sit down and write something about it.

It'‘ funny, but writing as a profession or as a vocation is an elucidating thing to do. I think I learned that on The News-Letter. There was a direct connection. I ended up being an author as well. The other thing that I did was run a consulting firm, but I think they just went together very well.

N-L: What positions did you hold before you were Editors-in-Chief?

CD: I liked being the Managing Editor. That was fun because that was getting everybody to get everything in and then laying out the paper and designing it, and then putting everything all together and going over to people and hounding them. They get their articles finished before you have your deadline.

JF: I was a Features Editor. Before us, there was a guy named Gary Moore. And before that, there was a guy named Herb Smokler. We were all friends with these guys. It was a real gang.

CD: It’s been a long, wonderful friendship that we’re had. It was sealed by becoming editors of The News-Letter. We were friends before that, but when we became editors, we found we could work together and get along and cooperate and get things done. It was really fun.

N-L: Is there anything else that you’d like to add?

JF: I looked up some old Hopkins yearbooks to see how they covered the crazy News-Letter. It was truly what I remembered, which is that these guys are right out of control. It gave a list of some of the articles that we did that made it into the Baltimore Sun, or that the Baltimore Sun picked up and turned into metropolitan news. And the same thing with the News-American. It gave a list of four or five of them. I didn’t remember it at all; it was wonderful. We did have a certain impact, I think.

CD: You never really get any feedback. I mean, the feedback you would always get would always be when somebody was pissed off about something. And that was usually Milton Eisenhower and everybody in the administration. Every time The News-Letter came out, we would get some kind of notification that we should come in. What was the name of the guy who was his assistant?

JF: Ross Jones. Ross Jones was famous, at least in my opinion, for having said the following. “These guys” — meaning Caleb and Jim — “have a cloud of shit over their heads everywhere they go.” I felt that we had been anointed with the most sacred of oils when he said that.

CD: Coming from Ross Jones, that’s like winning the Academy Award.

JF: I’ve never forgotten that. I think it’s the most wonderful thing. I have this image of this big black cloud of pooey, raining down.

CD: I don’t think anybody else even noticed it, but they were just sensitive to things being good promotional material for the University. That wasn’t always the case, and wasn’t always what needed to be reported.