According to a study published in Vaccine at the end of March, only half of adults in the U.S. claim they will accept the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible. Since the herd immunity threshold for COVID-19 requires that around 90% of adults be vaccinated or immunized through infection, public health experts still must convince a large segment of the population of the vaccines’ effectiveness.

The researchers who contributed to the study, which included experts from the School of Public Health, concluded that some people who are reluctant to get the vaccine may need to be convinced through targeted messaging.

In an email to The News-Letter, Matthew Dudley, one of the authors of the paper and an assistant scientist for the Institute for Vaccine Safety at the School of Public Health, explained the problems that could arise from a more general approach.

“One-size-fits-all generic messaging likely won’t work,” he wrote. “It may even backfire for some.”

Politics have played a heavy role in the pandemic, with safety measures made into questions of autonomy, dwindling trust in government institutions and leadership underplaying the pandemic early on. The political climate accounts for some of the hesitation. Some are concerned about the timeline of vaccine development and the effectiveness of the vaccine itself.

The researchers conducted a national panel survey to gather data. They created an 11-minute questionnaire in English and Spanish that reached 2,525 respondents. The panel purposefully oversampled Black and Latino responders as these groups have been undersampled by previous vaccine-related surveys. Participants answered a series of questions ranking their personal beliefs, their trust in public health institutions and their attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine. The demographic information for each participant was collected. In the analysis, the researchers made a few adjustments to reflect the sociodemographic distribution of the United States.

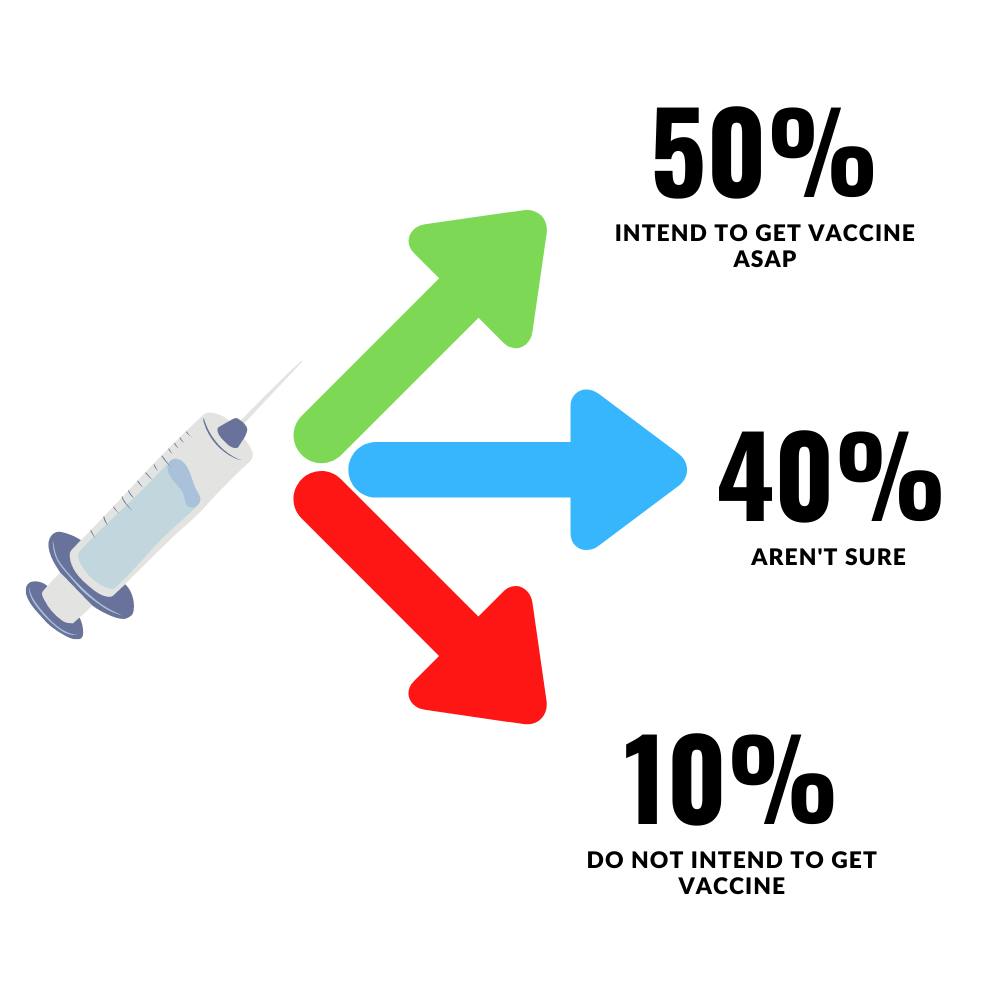

The researchers dubbed the 50% of participants who intended to get the vaccine as soon as they were eligible as the “Intenders.” The remaining 50% were split into two groups: 40% of participants wanted to wait and learn more before getting vaccinated, and 10% of the population claimed they would definitely not get the vaccine.

There were some demographic trends in these results. Intenders were more likely to be men, over 60, highly educated, Democrats and earn a high income. The Intenders also perceived COVID-19 as more severe, had high-risk conditions for COVID-19 and had more confidence in the vaccines’ safety. Their mindsets tended to be more community-oriented and equality-based.

The Wait and Learn group, compared to the Intenders, were more likely to be in good or fair health, less likely to report high income, less likely to be Democrat and less likely to have a high-risk condition for COVID-19. Around 52% of African American participants were in this group.

Many members of the Wait and Learn group reported having known someone that had a serious vaccine reaction in the past, were uncomfortable with sharing the personal information the government may require for the vaccine or were concerned that drug companies and the government experimented on people like them.

The Unlikelys, or people who claimed they wouldn’t get the vaccine, were less likely to be elderly or have completed higher education. Many participants in this category did not identify COVID-19 as a severe disease or did not consider the vaccine important to stopping the spread of the virus. They also had less trust in government institutions and more individualistic mindsets.

In order for herd immunity to be established in America, the Wait and Learn group has to be converted into Intenders. But how can that happen?

According to Dudley, specific messaging is critical to make the Wait and Learn Group want to get vaccinated. It could also be a good idea, he said, to broadcast the voices of those who have been successfully vaccinated to reassure people worried about the side effects of the vaccine. But messaging should go beyond that too.

“We need to understand what their concerns are, what they value and who they trust before creating tailored messages based on that information — addressing their concerns with respect, appealing to their values and partnering with trusted messengers,” Dudley wrote.

It’s important to get as many people vaccinated as possible, but even if vaccine numbers don’t reach the herd immunity threshold, public places may not stay closed indefinitely.

“Many are chomping at the bit to get closer to normality, even if it’s jumping the gun based on case numbers and vaccine coverage,” Dudley wrote. “But there are ways to open things up safely even if we don’t reach herd immunity right away.”

Dudley is in favor of vaccine passports, which might allow high risk locales to reopen safely. But his team has already noted a decrease in the number of people in the Wait and Learn group as more and more people are vaccinated.

The next steps for his team are continuing to survey the same panel to see changes over time and testing out different messaging styles to see what resonates with people hesitant to be vaccinated.