Recently, Texas faced its coldest weather in more than 70 years and concurrently experienced state-wide utilities failure. When temperatures in Texas dropped lower than temperatures in Alaska, more than 4.5 million homes and businesses lost their power and at least 70 people lost their lives.

To discuss these events, the Hopkins Energy Policy and Climate (EPC) program invited Jeremy Lin and Alex Gilbert to speak at the “Tackling the Texas Energy Crisis” event on March 2.

Lin is a director at Transmission Analytics Consulting company, which provides services for renewable energy developers. Gilbert is a project manager at the Nuclear Innovation Alliance, where his work supports climate mitigation. Both are lecturers in Advanced Academic Programs.

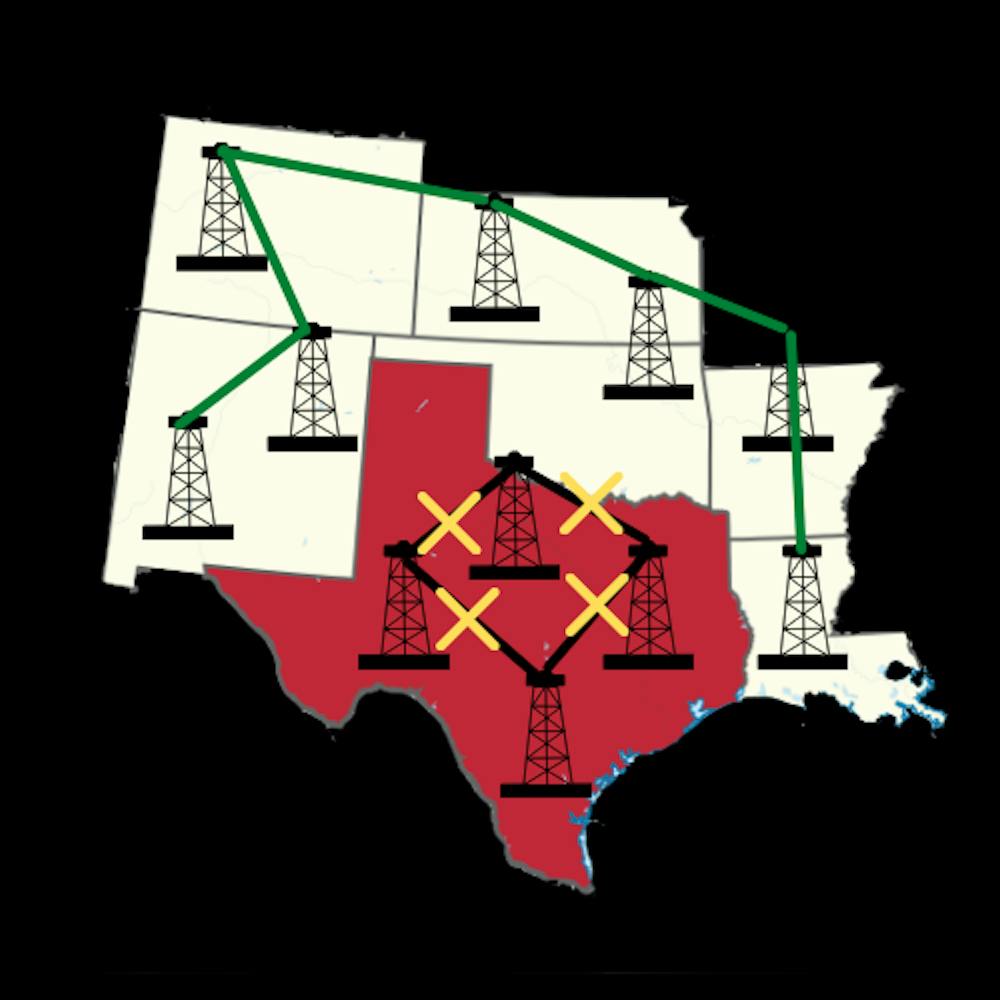

In order to explain the Texas power crisis, one thing has to be made clear first. Texas has its own independent power grid — Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) — which covers 90% of the state. Its three responsibilities are to operate the power grid reliably, to run a competitive electricity market and to conduct system and grid planning.

The panelists described how the severity of the winter storms took ERCOT by surprise, resulting in its failure to fulfill any of the three responsibilities. This in turn led to a wholesale collapse of the power grid.

Texas was not the only state in urgent need of power supply. In fact, the storms created a national demand for natural gas. As two-thirds of ERCOT’s power comes from natural gas, most of that supply became unavailable.

“[When] the natural gas system doesn’t deliver, it poses a reliability threat to the whole system,” Gilbert said.

According to the panelists, the unreliable operation of the power grid tipped the balance between energy demand and supply.

Unlike the rest of U.S. power grids, ERCOT is an energy-only market. This means that there is no backup method in the economy to compensate for energy problems. Lin explained that when there was a scarcity of power supply, a system-wide cap had to be implemented according to market economic theory.

“To reward those resources in this kind of scarcity situation, energy-only markets such as ERCOT came up with a kind of scarcity pricing plan, which essentially raises the ceiling for the energy price,” Lin said.

This action led to the price of a megawatt skyrocketing from $50 to $9,000. The inability of power plants and other energy resources to maintain a competitive market resulted in a $50 billion economic burden, which Texas will carry for the next few decades.

The most crucial factor for the wholesale breakdown of ERCOT, according to Gilbert, is the failure of system and grid planning.

In November, ERCOT’s seasonal energy demand level assessment estimated 67 gigawatts for the most extreme winter weather. Yet only two days after the storms hit, Texas already reached a 74-77 gigawatts demand. This was 10-15% higher than the theoretical maximum of energy supply, marking a record high even including past summers.

Due to the already severe nationwide natural gas demand, Texas was unable to find a substitute energy source that would satisfy all energy needs. In order to avoid having to cut the power grid out in a “black start” scenario, forced outages were put in place. But the outage rate was so high that many homes lost power and essential supply for more than three days.

Gilbert explained how many people suffered and even died due to poorly insulated houses. Although the lack of energy did not directly cause deaths, he said, it undoubtedly exposed people to life-threatening situations brought by the winter storms.

The panelists also addressed the allegations that the crisis was due to the failure of renewable energy sources, particularly wind energy. They said it was a well-known fact that wind turbines become less functional in extreme cold, so companies usually do not plan to rely solely on wind energy during cold weather emergencies. Gilbert explained that companies should draw energy from a variety of sources, including renewable energy sources, to buttress their supply.

“Energy diversity is the foundation of supply reliability,” Gilbert said.

The panelists described some difficulties for ERCOT to initiate any major changes in preparation for a similar event in the future. As ERCOT is a completely independent system, it is unlikely it will change its structure and build interconnections with other grids. Additionally, they explained, there is little market incentive for power plants to undergo extremely costly winterization.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Chris Burk, a graduate of the Hopkins EPC program, offered an analogy to illustrate the source of the crisis.

“Without interconnections to other networks and without winterized plants, the Texas grid was like a trapeze artist operating without a net,” Burk said. “The foundation of the problem was a highly complex and fragile electrical system that was overly reliant on a fragile gas system.”

The panelists pointed out that it is now time to encourage changes. They suggested the implementation of state policies to prevent another energy crisis.

However, Kelli Fereday, a graduate student within the EPC program and a Texan who lived through the crisis, expressed her disbelief in an immediate state-level change of energy policy in an email to The News-Letter.

“I do not believe there will be any substantive changes until a new governor is elected and until 2023 when the legislature meets again, unless this is kept in the limelight and he calls a special session, which he will not do,” Fereday wrote.