In January, I leave the woods where I live for the first time in 10 months. I settle into a new apartment, spending days memorizing its layout and cutting down big cardboard boxes with all my old possessions. I breathe in the golden-syrup sun from my new windows (a stark contrast from the eternal night of my sophomore dorm) and enjoy tea while reading. The truth is that it is quiet, and it is empty. If this were a fairytale, the story would be over; the danger would have passed, marriages would have happened and the entire kingdom would live in peace, happily ever after.

One day, I grab a coffee from a local cafe and have to ask the barista to repeat themselves three times when they ask what type of milk I want in my latte (oat, for the record) because I can’t read their lips. While walking back home from the grocery store last week, I pass a group of unmasked high-school-age boys. I spend the entire next few days worrying about being exposed to the virus until my test results come back in.

The other day, as I was trying to sleep, whoever lives above my apartment was blasting Adele and solely her saddest songs. It was as if someone’s being was trickling down from the ceiling, and I just lay there, staring at the wall until my vision turned blue, vaguely remembering the lyrics to “Someone Like You.”

This is not a fairytale, but it is. Messages go unheard and unaddressed. Daily moments are charged with danger and the underlying knowledge there’s nothing you can do about it. There’s a sort of magic in the air — tiny moments seem much more important than they previously would have — and I can’t escape it. Lately, though rarely, when I leave my apartment to run an errand, I’ll sometimes come across a friend I haven’t seen since last March. We’ll talk for a bit, standing on the concrete in the cold. They’ll tell me what they’re up to, and I’ll give my summary of the last year, but I don’t think they hear me. Then we go our separate ways, off to buy eggs or pick up a prescription from the pharmacy or return home to study.

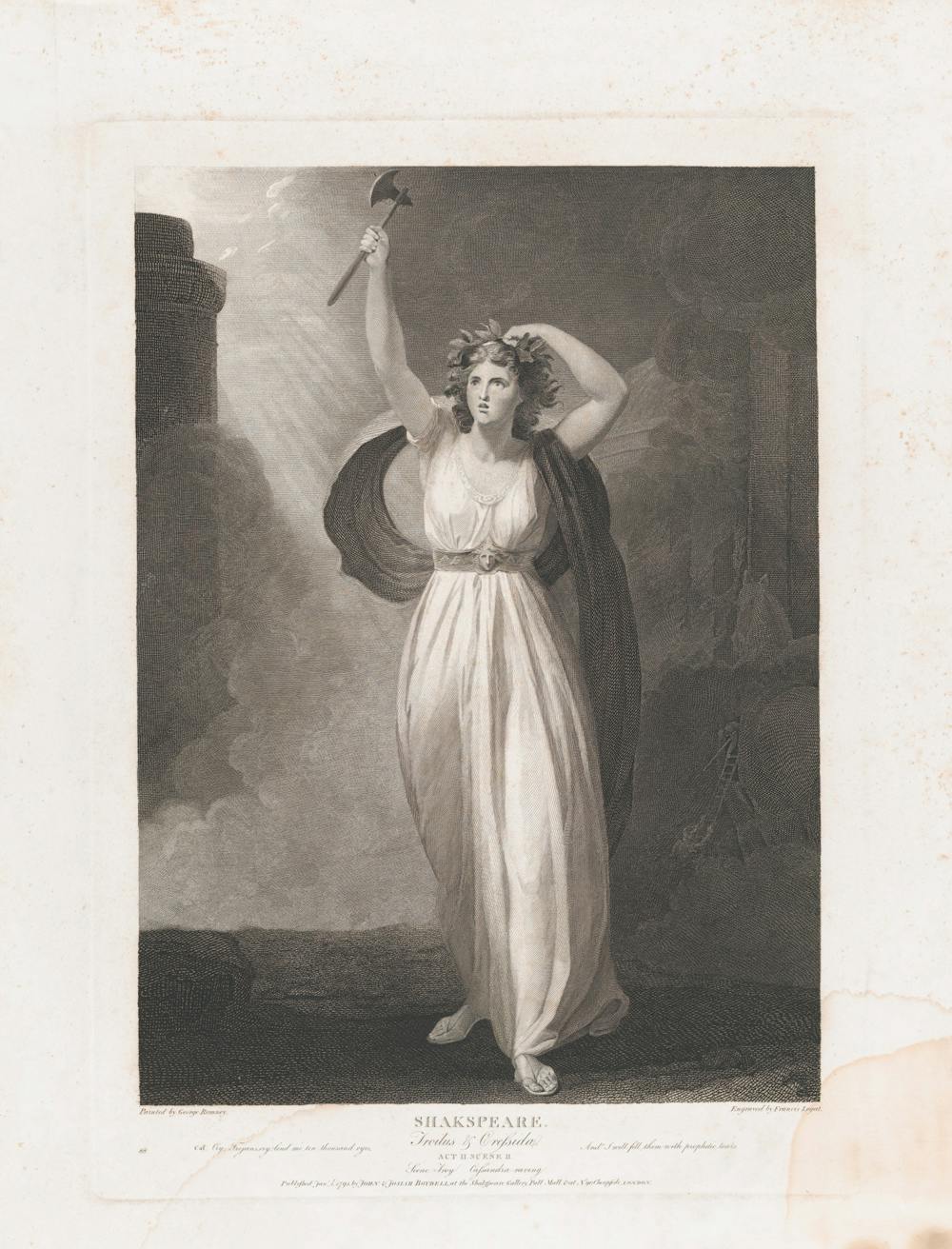

I can’t help but feel like Cassandra of Troy, who was cursed to know all these prophecies but be forever unbelieved. It feels as if I keep trying to impart something important when I have these encounters, but no one will believe me. I have these moments where I get so frustrated that all I want to do is shake someone by their shoulders and tell them what I have to say.

The problem is that I don’t know what that something important is. It’s speaking without speaking, knowing without knowing, thinking without thinking. What I mean to say is, my words carry weight due to an unknown gravity. What I mean to say is, it is snowing, and every snowflake is something I need to say. What I mean to say is, Cassandra had her prophecies, I have my stupid mouth, and yet I’d still love to be listened to by someone who wants to listen.

I turn on the faucet to brush my teeth, and prophecies rush out. I fill a pot with prophecies and boil it on the stove to make dinner in. I open the window in my bedroom, and I have to close it before the wind suffocates me with prophecies. What does one do with so many important things that no one will care about? I pack some prophecies up in boxes, wrap others in tiny threads and even try to breathe them in. But there are so many of them and only one me. There’s only one me and so many truths to be said. How does one even tell the truth? How does one even get out of the woods? Where does someone arrive once they’ve done that?

This is not a fairytale, but it should be. My life now is so quiet that the silence has unspooled; it wraps around everything around me and of me, but it’s loosening its grip. The knot in my throat is unraveling and unraveling, and I can pull at the thread on my tongue now. I think my problem was that I misunderstood. I thought that the woods were the place where all the issues in fairy tales came from. I was wrong.

The woods were where all the issues were resolved — Little Red Riding Hood has to confront her independence among the trees, Hansel and Gretel have to come to terms with the consequences of their childhood when they arrive at the witch’s house. The woods are the solution, not the instigator. They are the medium through which one passes, not the body that passes through a medium. They don’t tell the truth; they just coax it out of you.

Perhaps, like Emily Dickinson, I must “tell all the truth but tell it slant.” I must allow the truth to catch the light. When I have caught it, I will scoop the light out of the truth with my fingers and smear it against the walls to chase all the shadows away. I will piece all these prophecies together until they are too large to be ignored. I will sit down, / enjoy the quiet / and learn to love the afternoon. I will take all the threads of silence and dump them out of my window. I will make the truth my, even our, medium to pass through.

And so... the truth will bubble up from the floorboards. The truth will trickle down from the ceiling. The truth will exist in every glance, every breath, every movement of every muscle. It will exist in every snowflake, every cup of coffee, every unheard word. It will live in me, in you and in everyone you’ve ever known. It will pass through your dreams like a thick wind. And now, now it can’t be ignored because the truth is everywhere, and we have no choice but to pass through it.

Ryan Aghamohammadi is a junior studying Writing Seminars from Woodbury, Conn. His column uses the occult and the supernatural to cast a light on his ongoing journey of self-discovery.