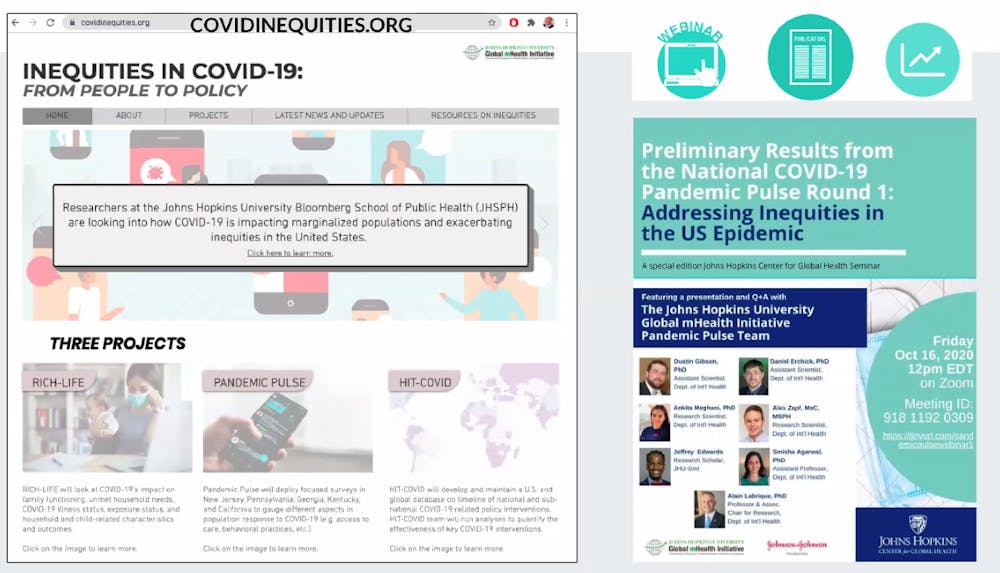

The Hopkins Center for Global Health hosted its new virtual seminar series on Feb. 3 with the first of a two-part seminar titled “National Pandemic Pulse: Findings from a U.S. Representative Survey in December 2020.” National Pandemic Pulse is part of an initiative by the University’s Inequities in COVID-19 project tasked to monitor the effects of the pandemic on low-income and minority groups in the United States.

Guest speakers presented results from Pulse’s second round of surveys collected from Dec. 15 to Dec. 23. The questions in the survey explored different topics related to COVID-19, including pandemic fatigue and the public’s trust in science.

The seminar was moderated by Alain Labrique, director of the Pandemic Pulse team, and featured Daniel Erchick, Smisha Agarwal, Alex Zapf and Prativa Baral as guest speakers to explain the findings from the survey. All speakers are affiliates of the Bloomberg School of Public Health and helped collect and analyze the data.

Recent studies have demonstrated members of racial and ethnic minority groups are at a disadvantage when it comes to vaccine distribution. The results from National Pandemic Pulse surveys are critical to understanding how racism in a socioeconomic framework has impacted other facets of the pandemic.

“This is really what motivated us to embark on this work — to shed more light and data on this challenge that has been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic but existed long before the pandemic began,” Labrique said. “It is really critical for us to acknowledge that racism kills, whether this is through force, deprivation or discrimination.”

He hopes that their results will help other researchers derive mitigation and intervention strategies to compensate for inequities in health.

Trust in Science

Baral illustrated the results of the “Trust in Science” module of the survey. She stressed that science has a history of racial discrimination, and it is important to recognize the barriers reinforcing lack of trust.

“Historical precedence indicates that science hasn’t always been the kindest to our racial communities and that’s putting it lightly,” she said.

Overall, 76% of respondents reported trust in science, with Black and American Indian communities exhibited lower levels of trust in science. Republicans also reported lower levels of trust when the data was stratified based on political affiliation.

Additionally, based on the results, participants trusted COVID-19 information coming from primary care physicians the most. Participants trusted health information from social media the least.

Baral emphasized that the results of this study indicate that health-related information should be purposefully disseminated to the public, especially during a pandemic.

“For those of us trying to get information to the public, differentials across race and ethnicity are likely to present challenges for messaging and long-term and short-term building, since these problems arose even before the pandemic,” she said. “We need to think more about trust in a long-term fashion because it takes time to build.”

Pandemic Anger

Zapf described the survey module about pandemic anger, which is experienced by people who believe that the pandemic is a hoax or is politically motivated.

“We’re experiencing one of the biggest social experiments in human history right now,” he said. “I’m sure that most of us have been affected by some form of home order in the past 12 months, but this hasn’t always been met with compliance.”

The results indicated that young Americans, especially those who identify as Black or Latino, are more likely to disagree that COVID-19 is a serious concern. Additionally, 40% of Republicans disagree that the pandemic is serious and over 50% of them are angry at experts. In contrast, 90% of Democrats agree that COVID-19 is serious, and only 25% of them expressed pandemic anger. Overall, one in every three Americans are angry at public health experts.

“It is important to acknowledge that the majority of the U.S. still agrees with restrictions and stay at home orders to benefit population health, and the majority of Americans are concerned with COVID-19,” he said.

Zapf underscored that the resistance posed by the public needs to be addressed more proactively.

“The public health policy implications are really important since resistance against public health interventions has various detrimental effects, such as continued or accelerated spread, societal instability and economic damage,” he said.

The module about pandemic anger piqued the interest of Safia Jiwani, a research associate at the Bloomberg School of Public Health who attended the seminar.

“I haven’t seen other analyses measuring perceived anger during the pandemic, and although it seems surreal (being a public health professional myself), that people are angry at public health experts, I think the analysis is innovative and crucial to inform adequate responses,” she wrote in an email to The News-Letter.

Risk Perception

Erchick discussed the module of the study which evaluated the public’s perceived risk regarding activities, such as attending large gatherings, dining outdoors, going to the grocery store and accessing health care. According to Erchick, 33% to 81% of respondents believed that those activities were unsafe. These numbers demonstrated an overall increase compared to the first round of surveys.

“The main takeaway is that a higher proportion of older respondents perceived activities as unsafe relative to younger [respondents]. However, young people saw going to the grocery store and accessing health care as more unsafe,” he said. “In terms of race, there is higher perceived risk among African Americans, Hispanic and Asian American respondents and lower perceived risk among Caucasian and American Indian and Alaskan native respondents.”

Additionally, he noted that Democrats and independents perceived more risk compared to Republicans. There was also higher perceived risk among low-income participants.

Based on this data, Erchick recommended that younger people, men and Republicans, notably who identify as Caucasian or Black, should be especially encouraged to engage in preventive behaviors. Future projects should identify and study the factors that lead to higher risk perceptions among the minority and lower-income groups.

“Our findings raise questions about systemic racism and similar barriers that could be driving higher perceptions among disadvantaged groups and the influence of lived experiences during the pandemic,” he said. “Interventions should be focused on disadvantaged groups with the goal of increasing health equity.”

Prenatal Care for Pregnant Women

Agarwal presented the results on how the pandemic has affected health services for pregnant women. She asserted that while there is no indication that women are more susceptible to COVID-19, pregnant women still incur physiological changes that make them more susceptible to diseases overall.

Based on the results, Agarwal explained that 30% of pregnant women experienced cancellation or reductions in the frequency of prenatal visits, and 25% of women had to change their prenatal care provider. As a result of these disruptions, 38% of pregnant women reported higher levels of distress compared to 24% of non-pregnant women.

She also stated that analysts used the USDA Household Food Security Survey Module to assess food insecurity within the population. They found that pregnant women, particularly Black women, are more likely to experience food insecurity.

However, Agarwal emphasized that the sample sizes used to study associations by race and socio-economic status were limited, and more research still needs to be conducted. Her team plans to assess pregnancy-related outcomes in its next set of surveys.

The National Pandemic Pulse project is an ongoing initiative. The team plans to conduct an additional four national surveys in the coming months, spaced out by six weeks.