University President Ronald J. Daniels reported on Oct. 15 that the University ended the FY20 fiscal year with a surplus of $75 million due to mitigation efforts. These efforts, which include salary and hiring freezes, will be kept in place until the end of the school year.

Without austerity measures, the University had anticipated losses of $100 million from the FY20 fiscal year. Daniels added that the projected deficit for the current fiscal year has decreased from the $375 million predicted in April to $73 million. He explained that the deficit would have been twice as high if not for the University’s actions in early April.

“We initiated a multiphase plan that sought to preserve the health and safety of our community; continue to deliver on our education, clinical, and research missions; and respond to the needs of our local and global communities... while also ensuring responsible financial management of our $6 billion-plus enterprise,” he wrote. “Foremost among our priorities was the need to limit, to the greatest extent possible, layoffs and furloughs of members of our workforce.”

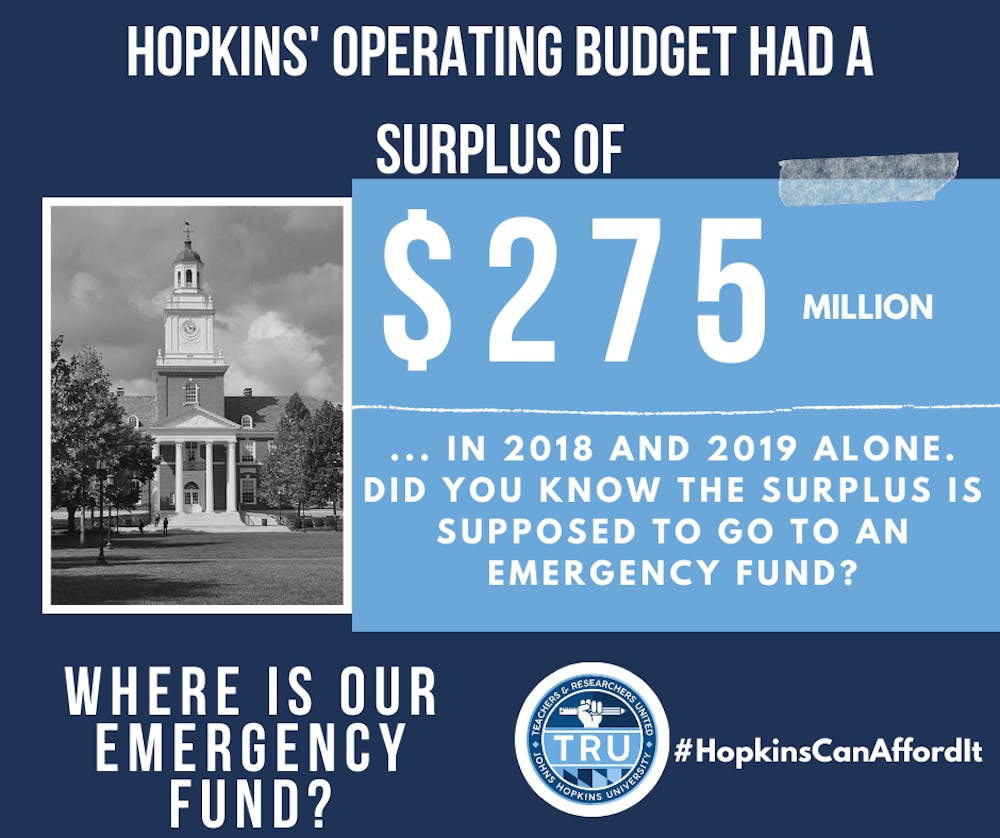

Alex Parry, 4th-year PhD History of Medicine student, and Peter Weck, 5th-year PhD student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, are representatives of the unofficial graduate student union Teachers and Researchers United’s (TRU) organizing committee.

According to Parry and Weck, the budget surplus is inexcusable given the current situation. They questioned where the surplus will go if it is not being used to help the most vulnerable of the University’s workers.

“It is really profoundly disrespectful to congratulate themselves and thank us for our sacrifices for helping them cut the deficit and reach this surplus when we’ve been asking and begging them for the basic support graduate students need to pay the bills for six months now and have just gotten empty promises,” Weck said.

François Furstenberg, a History professor and co-secretary of the Academic Council, was one of the faculty members who spearheaded the petition delivered to Daniels last June in response to the University’s austerity measures. In an interview with The News-Letter, he described the impact of the petition on how the University handled financial matters moving forward.

“It brought immediate attention to some of these issues, in particular the lack of transparency and to the process of making decisions. Faculty were very upset at the speed at which these decisions were made and the way in which they were made, really with no faculty input,” Furstenberg said. “It highlighted what I see is a major problem of governance in the institution.”

In terms of transparency, the University began holding virtual town halls to discuss the financial details that many faculty and staff sought. Furstenberg noted that the University also created a Pandemic Academic Advisory Committee that included faculty leaders who were elected, rather than selected by the President. In addition, the Faculty Budget Advisory Committee began publishing its meeting minutes online in an effort to publicize more information.

“That’s a tricky committee because the information shared is what the University chooses to share. It’s purely advisory and membership is handpicked. It’s not the same as having an elected faculty body,” Furstenberg said.

In the email, Daniels announced that, as of now, Hopkins will not be taking any further mitigation efforts until the end of the current fiscal year. However, the University will be keeping its current measures in place to prepare for further expenses from the second surge of COVID-19 cases, as predicted by the University’s public health team for the winter season.

Furstenberg stressed that, while he is pleased that the University’s finances are in a better place than expected, the administration made the initial projections too early on with little and unreliable information. According to Furstenberg, the University should prioritize protecting the vulnerable members of the community by restricting furloughs and salary reductions.

“Faculty aren’t the most vulnerable. Budgets reflect institutional priorities,” he said. “Low-paid staff, graduate students, junior faculty, untenured faculty — these are the people who are the most vulnerable right now and where real investments should be made, not building projects, which are very low priority in my book.”

Agreeing with Furstenberg’s arguments, Parry and Weck highlighted that the University can only benefit from investing in its workers. They stated, however, that the University seems too focused on preserving its endowment.

They doubt that the austerity measures will be lifted unless community members are able to demand the University set its priorities straight.

“What do you think is going to the pool of graduate students who apply here? You are going to get better graduate students producing better research, increasing their chances in the job market producing better publications. If you invest in your workers, your workers will get better returns,” Parry said. “If you have poorly treated and compensated workers, not only is the University shooting us in the foot but also shooting themselves in the foot.”

Weck emphasized that all graduate students have been affected by the pandemic and the University’s austerity measures.

“For some people, it’s a much more extreme effect, especially people who have to perform fieldwork or human subject experiments as part of their dissertations. Some of those people have lost their funding entirely and are being forced out of their programs,” he said. “They have had to scrape together savings loans and additional wage income to feed themselves and make sure they can stay in good housing.”

In partnership with groups like the Graduate Representative Organization and the Graduate Student Association, TRU petitioned the University for a one-year extension of funding for all PhD students in late March.

As a result, however, the University only gave small amounts of money for students who could prove their dire financial need. Others were redirected to apply for help from the emergency relief fund, but this source was quickly depleted.

Furstenberg believes that the University’s decision making has become increasingly centralized, detaching Daniels and other administrators from academic life. He reasons that this is why the University was so quick to cut the research and teaching funding first to maintain the stability of the finances.

“The finance of the University exists to support the academic mission of the University. I often get the sense that that priority has been reversed, that preserving the finance of the University is more important than maintaining the academic mission of the University,” he said. “That’s been difficult for me to watch.”

Parry illustrated that the pandemic has intensified existing inequalities for resource distribution across the University. Some well-funded departments in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, such as the Political Science department, were able to offer funding extensions after receiving pressure from graduate students in their department.

Not all students, however, had the same benefit, and for most, their funding depends on their ability to complete their research.

“The place where these measures are immediately hitting hardest are humanities students. I haven’t been able to get into an archive for months now, and I still cannot get into any archives,” Parry said. “We’re looking at as much as a year in research delays that are not gonna be compensated unless we are able to get external funding. We are more or less expected to bear the brunt of this on our own.”

Furstenberg also noted that Daniels’ salary remains among the top 10% of University leaders, even with the salary reduction he took.

“It would be a generous move for him to donate all the money that he receives from outside board membership to faculty, staff, junior faculty and graduate student stipends,” he said. “That may be a move sort of like a publicity stunt, but it would help give a sense that sacrifice is being shared broadly, rather than sacrifice being imposed on those who were the least capable of bearing.”

At the start of the pandemic, Parry and other graduate students calculated that it would cost $41 million from the University to extend all PhD students for a fully funded year that included health care and basic necessities, accounting for grants that compose a large portion of graduate student funding. He shared the cost-analysis sheet with The News-Letter.

“There is no ethical argument to saving money when everyone else is scrimping and saving and losing housing,” Parry said. “If you lose $30 million as a graduate student you’re in deep trouble. If you lose $40 million as a university with $75 million budget surplus and a multi-billion dollar endowment, it is not really going to affect the University.”

Breakdown of the University’s finances for FY20

During a town hall meeting held on Oct. 21, Helene Grady, vice president and chief financial officer, presented on the timeline of the University’s finances since the pandemic began.

Grady explained that COVID-19’s impact decreased from $100 million to $50 million by May. The University only experienced one quarter of severe financial losses from COVID-19.

“The $75 million surplus result for last year has much to do with how strong a year our JHU divisions were having through the first three quarters of the year headed into the pandemic. We are really fortunate that it was a very strong year through March,” she said.

She added that the University also received one-time revenues from the federal CARES Act and contributions from the Health System to the School of Medicine that helped alleviate the projected losses for FY20, which lessened the projected deficit by $65 million.

According to Grady’s presentation, the $375 million estimate in losses for FY21 was made before accounting for savings from the austerity measures. The net loss of $73 million projected for FY21 incorporated the savings from the University’s Phase Two of mitigation measures at a divisional level and updated impacts from COVID-19.

The measures included the salary freeze and reductions for leadership for FY21, staff hiring freeze and a one-year suspension of retirement contributions.

For the spring budget, the University is also estimating an additional $42 million in clinical revenue compared to the March prediction. Though still 13% below pre-COVID-19 levels, it is intended to lessen future losses.

Grady emphasized that while the University enacted a 10% reduction in tuition rates for undergraduate students, which was followed suit by the graduate schools, the unexpected high enrollment rates for the present school year totaled an additional $24 million in savings for FY21.

“So much has been in flux with net tuition and fees over the summer. Even with those changes on tuition rates and financial aid, we were able to update our budget projection for net tuition in September because enrollments are actually very strong,” she said. “Enrollments beat our projects, and we are able to recognize that now.”

According to Weck, the University has only run a deficit once in the last 25 years, and it easily earned the money back the following years. This figure further supports Parry’s belief that continuing the austerity measures is unnecessary.

“The surplus demonstrates that the austerity measures were too extreme to begin with,” Parry said. “They are looking at a short-term horizon where the only thing that matters is the next two years, rather than the next decade or century.”

TRU’s priority, Weck said, is to give graduate students an institutional voice to influence their role within the University. He added that, due to the administration’s increasing centralization, TRU has been largely unsuccessful in this goal.

Parry called on Daniels to allow graduate students to be a part of the decision making process. Following Furstenberg’s petition, the administration has recently made efforts to include faculty in their meetings.

“We can talk all day, and we’ll talk all day as necessary about graduate student funding, health care, work safety, but it ultimately all goes back to the same problem,” Parry said. “The only way forward from that is if the University allows us to unionize and have a seat in the table.”