As the coronavirus (COVID-19) continues to spread, Hopkins is actively making efforts to combat the pandemic by integrating dozens of fields of expertise to find solutions.

Nine specific research areas have been established to achieve this ambitious goal: community research; diagnostics; health worker protection; host pathogenesis; medical supply innovation; modeling and policy; therapeutics; viral genetics; and viral immunopathogenesis.

Hopkins has placed strict restrictions on who is allowed work on campus. Currently, undergraduates and first-year graduate students are not permitted to work on COVID-19 research, due to the risk of infection.

Leaders of each research area were selected by Hopkins to serve as liaisons to University leadership, identifying ways to support investigators and minimize any barriers during this critical time.

The News-Letter interviewed three investigators, each of whom is part of a different research area.

Dr. Stuart Ray, an infectious disease control specialist at the Hopkins School of Medicine, is currently part of the viral Genetics research group. Before taking on his current role in COVID-19 research, Ray was involved in a number of projects trying to build data repositories and other registries and biorepositories. Ray is also the vice chair of medicine for data integrity and analytics and a co-chair of the research sub-council of the School of Medicine data trust with Dr. Chris Chute.

Ray explained that the aim of the viral genetics research group is to study the genomes of the COVID-19 virus in order to trace the history of the epidemic in a greater picture.

“In order to understand epidemiology, pathogenesis, immunity and drug treatment, we need to understand the virus,” Ray said in an interview with The News-Letter.

Ray posed many questions about the specific properties of the virus. Did a single strain or multiple strains of virus enter the mid-Atlantic region? Do the strains have biological differences?

What sequence does the patient initially have and does that sequence change over time? Did the patient go on antiviral therapy? Is the therapy specific to a viral protein like a protease inhibitor or a polymerase inhibitor?

Through their efforts to answer those questions, they are grasping a fuller understanding of how the virus comes about and where it could potentially end up.

Ray noted that one key part of the project is to keep the linkage between the viral sequence and the metadata from the patients being treated for COVID-19.

“It is important to know as much as possible about the people who are affected and people who are unaffected, and people who are more or less severely affected in order to understand what modulates those risks,” Ray said.

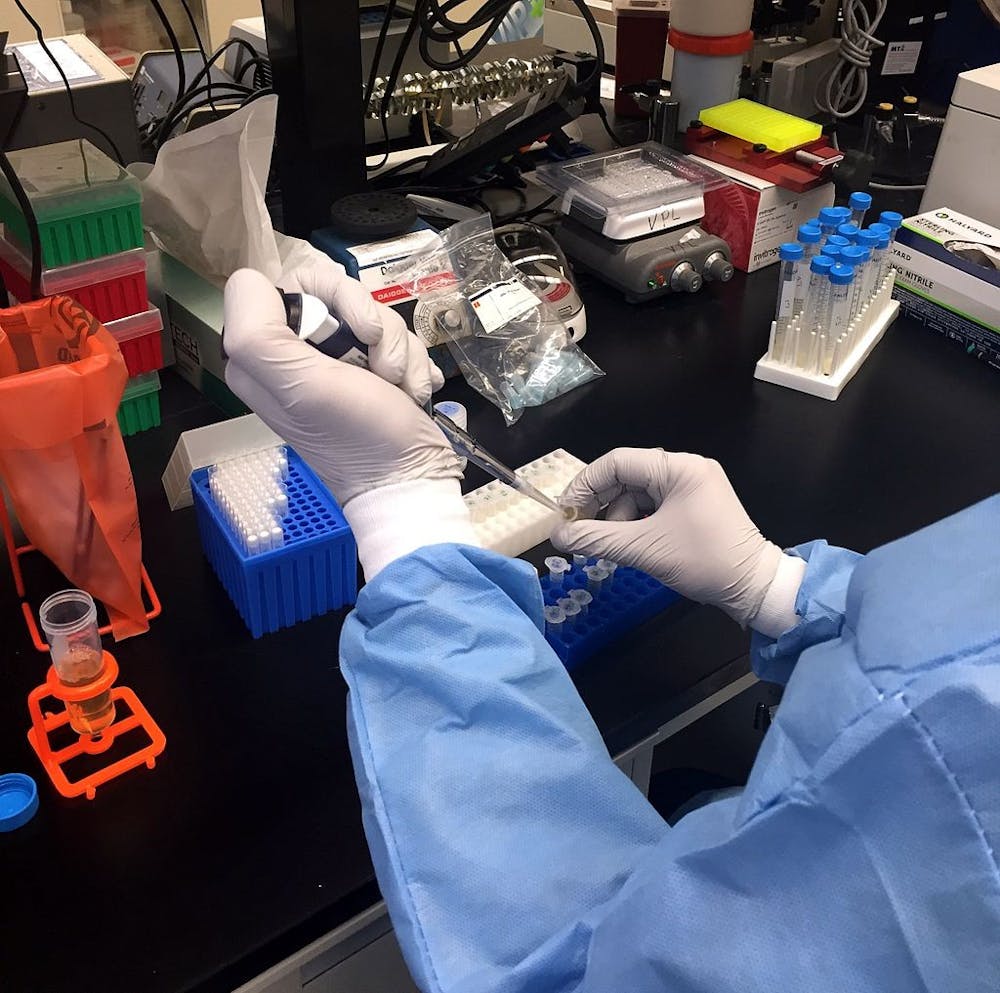

When asked about the current conditions of their research project, Ray mentioned that use of collaborative tools, such as Slack and Zoom calls, have proven to be extremely effective for discussions. Except for the researchers handling human specimens on campus, who are working under strict conditions, the rest of the team is able to analyze the data remotely.

Since mid-March, when the COVID-19 research projects were established, the viral genetics research group has already obtained a draft sequence of genomes of the virus from people who have been cared for at Hopkins Hospital.

Those data are being prepared for sharing with the wider community. In the meantime, the group is actively collaborating with other departments and research groups, including pathologists, radiologists, biomedical engineers and the Applied Physics Laboratory. Ray explained how this collaboration has helped develop their understanding of the illness.

“When all of us are talking, it means we are forming a picture of what that elephant looks like.” Ray said.

As Ray and his colleagues strive to figure out the shape of the elephant’s trunk, Dr. Justin Bailey, who is part of the viral immunopathogenesis group, is trying to measure the size of the elephant’s body.

Bailey is also an infectious disease physician, and his research expertise is in B-cells and antibodies which are broadly applicable to studying antibody responses against other viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the technical name for the COVID-19 virus. Bailey is one of the lead investigators on the immunopathogenesis of the virus, and work in his lab will be led by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Nicole Skinner.

The hypothesis of Bailey’s group centers around the idea that exceptional antibodies, produced naturally by some individuals, could block the ability of the virus to cause infection. The current aim of their project is to isolate neutralizing monoclonal antibodies from individuals who recover from SARS-CoV-2 infection. The specific antibodies are called neutralizing antibodies, which could be isolated and rapidly produced on a large scale for use as a treatment for severe COVID-19.

While Bailey and his colleagues are measuring the width of the elephant, still others are measuring the length and the height of its body. Within the viral immunopathogenesis project, there are many collaborations between groups trying to better understand the basic mechanism of the virus.

“We are working with a larger group that will evaluate many aspects of the immune response against the virus, including innate immune responses, T cell responses and antibody responses,” Bailey said in an interview with The News-Letter.

On the other side of the elephant, Professor Shruti Mehta is trying to figure out the shape of the elephant’s tail. Mehta is deputy chair of the department of epidemiology at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Along with two other faculty members from the School of Nursing and the School of Medicine, Mehta was selected to lead the efforts of this community research project.

The general aim of the research group is to find the effect of COVID-19 on at-risk populations across all age, social and economic divisions. As the group is still in the developing stage, Mehta and her colleagues have been meeting for the past two weeks to develop a proposal, begin research activities and establish their team.

Like the other COVID-19 research groups, Mehta noted that their effort to respond to the pandemic is not a one-man job, but rather a coalition of experts in all fields of expertise.

“All of the efforts are being developed collaboratively with other members of the community research group, which has representation from the Schools of Public Health, Nursing and Medicine,” Mehta said in an interview with The News-Letter.

Nobody knows what the elephant that is COVID-19 looks like. However, Ray believes that scientists from all fields can work together to reveal its exact appearance.

He expressed his determination with a quote from the film The Martian.

“We need to science the shit out of this thing,” Ray said.