Evening meant clutching Amma’s hand and crossing Kachi Gali to reach the neighbors’ houses. After visiting Mehwish, it was Akbar ki amma’s (Akbar’s mom), as she was referred to, turn. We would stop by her house and the dusty living room, filled with placards she had embroidered herself. (“Welcome,” and, “Have a good day!” they proclaimed.) Akbar ki amma was old, and I never knew her name; she was always just Akbar ki amma, and her house seemed very lonely and empty. Amma reminded me that is why we must always visit her.

On our way back I would stop by at Taimooria, the one-stop shop not bigger than my Charles Commons room, that I would go to for snacks. Two uncles would sit behind the counter and retrieve the usual — two Dairymilks that were five rupees each. Amma — actually my aunt who is like a second mother to me — would remind me that the other was for my sister and I would reluctantly agree. On our way back, aunties would be standing outside their gates drinking chai and gossiping, and Amma would stop to get the usual tea, in both senses of the word, while I tugged and tugged at her hand wanting to get back home so I could eat my chocolate.

Afternoons after coming back from school would be reserved for Dadi Amma (Grandmother). As soon as the bus dropped me off to my house, I would run through the blue gates, through Asim Chachoo’s room (who lived in England but really in North Nazimabad, Karachi, Pakistan) and to my dadi amma. She would usually be in her customary white chicken shalwar kameez (traditional combination dress) and sitting on a chair with a jainamaz (prayer rug) in front and a tasbeeh (prayer beads) in hand. I would jump on her lap and kiss her cheeks as she would ask me how school was. Her grey hair, always oiled back into a braid, would be undone and then redone by me — messier than before, but Dadi Amma never complained.

Sometimes at night there would be load shedding, and we would all crowd into Dadi Amma’s room — the only room with the UPS connection. We would wait it out, but if it was one of those 24-hour affairs where the UPS would give out, there was always the door in Dadi Amma’s room which we could open out to the sehen (courtyard), and there was always enough floor space to house the three families that lived in the Hydery house.

If there was electricity, Mama, Baba and I would sleep in the bed upstairs, while Fariha would lay down her mattress next to the AC, hogging all the cold air. Mama and I had a routine: She would tell me the story of Hazrat Musa and Hazrat Sulaiman (my favorite because he could do magic) and Hazrat Isa. After this we would recite Ayat-ul-Kursi and she would blow into the air — I guess blessing the molecules with the magic words. Mama would lie straight and extend her arm while my head lay in the crook of her shoulder and neck. If Mama came to bed late, Baba would do this routine, but I would tell Baba he was a horrible story teller. Both Mama and Baba’s extended hands never moved until I fell asleep.

Mornings were grumpy and uninteresting. Baba would iron our uniforms and polish our shoes (he still does to this day) while Mama cooked a horrible concoction of partially boiled egg yolk which she would shove into my mouth with claims of making me taller. Then the bus wala uncle would come and raise a living hell in the neighborhood with the amount of honking he would do as my sister and I ran inside the bus with Mama and Baba egging us on. (God forbid we miss it because being late to school was an automatic minus 25 points from our total tally of marks.)

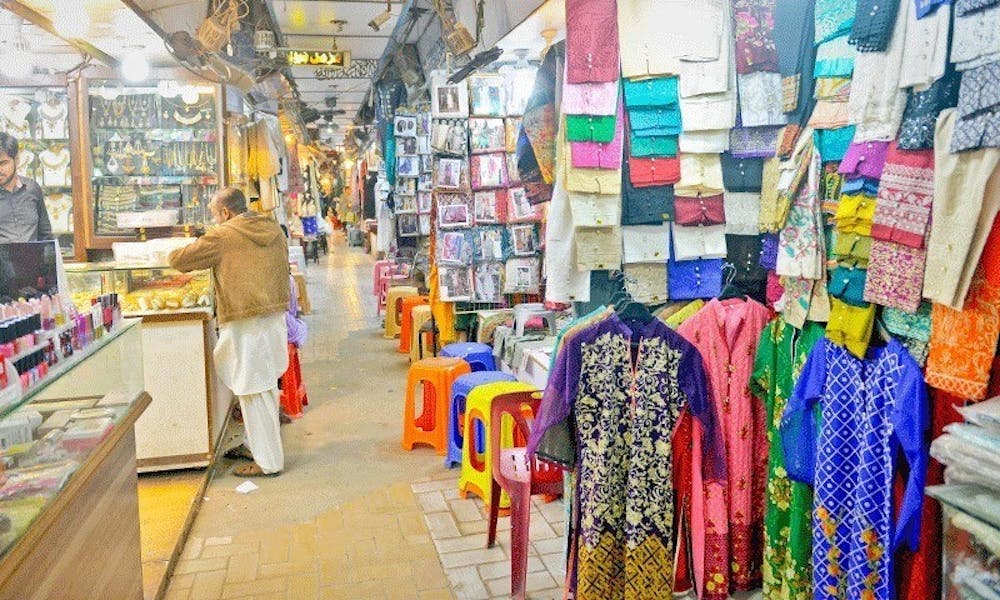

I grew up and I didn’t even realize it. I shifted continents, people, neighbors, electricity, water supplies and came to the first world. Congratulations to me — I have made it. I am not ungrateful, not at all. I am so lucky and so privileged. I get an education, the very best education. I get to wear what I want and do what I want and be who I want to be. I get a choice of churches, temples, synagogues, mosques and religions — I am free to choose my life and my religion and my God, but all I want is those moments of holding Amma’s hand to go to Aslam Market and the Azan happening midway. I crave the loudspeakers that would blast the call to prayer and bring the world to a halt, as if the crows would stop in midair to pay their respects.

Perhaps I have more freedom in the “free world” than I did in Pakistan, but I don’t have a home and I don’t have a family. I don’t have Taimooria and Aslam Market and I don’t have Amma and Abba and Mama and Baba. I don’t have a charpai (woven bed) under the stars and I don’t have a million mosquitoes who would form a black cloud over your head after Maghrib. I don’t have neighbors whose houses I frequent every evening and I don’t have an Akbar ki amma whose name I still don’t know but don’t need to know because the familiarity is enough.

I always have electricity and there is central air conditioning — a faraway dream in Pakistan. The water supply is constant and I don’t have to stop shampooing midway to yell to my dad “TURN ON THE WATER” because the slow trickle from the shower head has finally fiven up. I have everything my mind could want, but my heart — oh, my heart is empty. I gave it to Pakistan a long time ago.