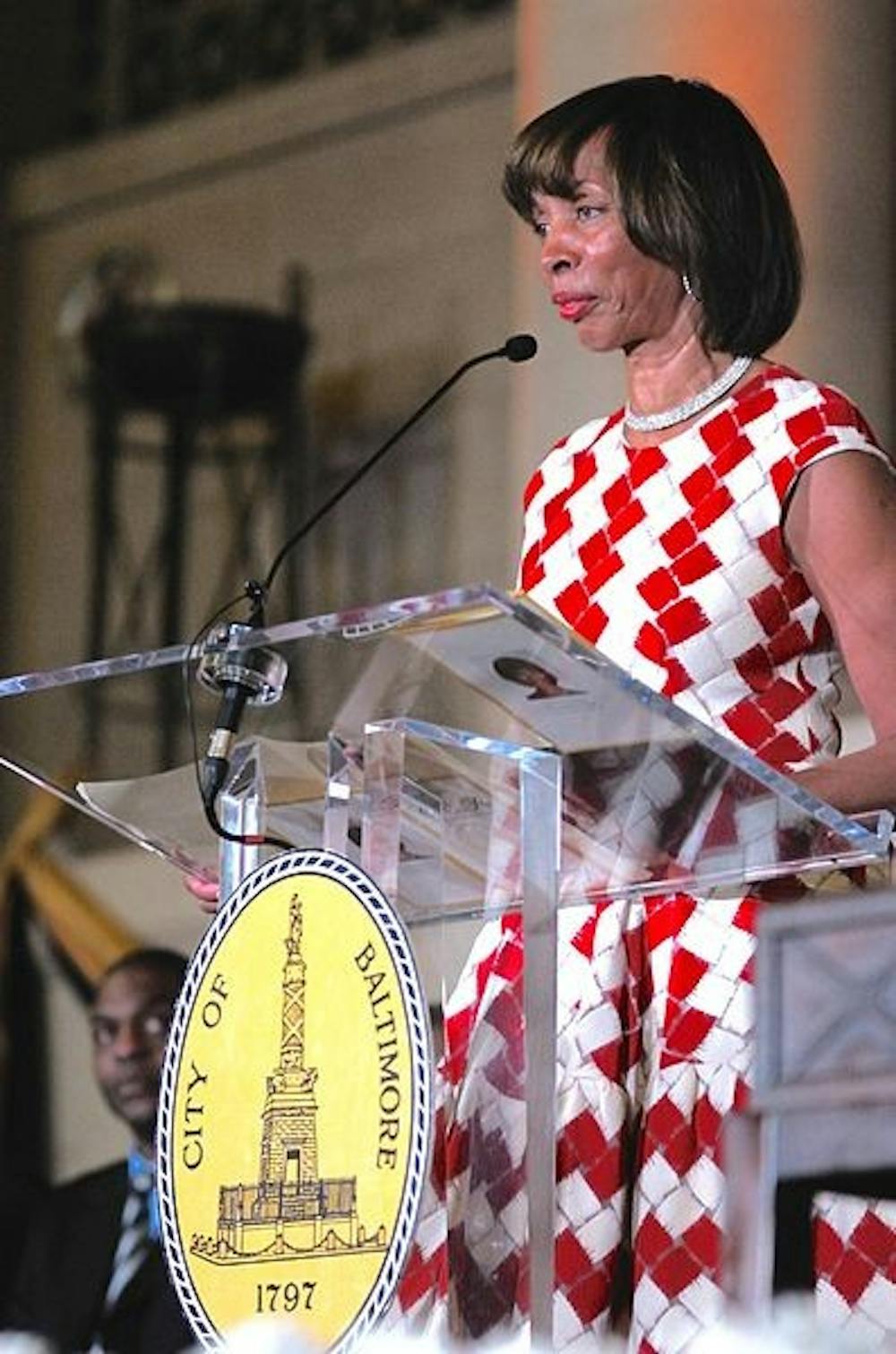

Former Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh was sentenced to three years in prison and then three years of supervised release in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland on Thurs, Feb. 27.

She had pled guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud, conspiracy to defraud the government and two counts of tax evasion in November. Judge Deborah Chasanow also ordered Pugh to forfeit nearly $670,000 and pay the University of Maryland Medical System $400,000 in restitution.

Last April, The Baltimore Sun reported that she had engaged in unethical activity surrounding her children’s book series Healthy Holly. It was reported that Pugh exchanged city contracts for book sales and had received over $500,000 from the University of Maryland Medical System for 100,000 copies of the book.

In a public statement regarding Pugh’s sentencing, United States Attorney for the District of Maryland Robert Hur explained the importance of prosecuting public corruption cases, particularly in Baltimore.

“Baltimore City faces many pressing issues, and we need our leaders to place the interests of the citizens above their own,” Hur said. “Catherine Pugh betrayed the public trust for her personal gain and now faces three years in federal prison, where there is no parole — ever.”

While prosecutors sought a five-year prison sentence for Pugh, her defense team argued for a sentence of only a year and a day.

For senior Evan Drukker-Schardl, the exact details of Pugh’s sentence were not very consequential as the sentence would not fundamentally change Baltimore’s culture of governance.

In an email to The News-Letter, he explained that he is not optimistic that the conviction will serve as a deterrent to future corruption.

“What Catherine Pugh did is emblematic of a culture of corruption that runs through the Democratic Party in Baltimore, and prison does nothing to change the structural incentives to profit off of public service,” Drukker-Schardl wrote. “Many of the leaders responsible for acting in the public interest and preventing corruption are involved in a Party machine that rewards and inculcates corrupt and unethical practices.”

Senior Ally Hardebeck echoed this sentiment in an email to The News-Letter, agreeing that Pugh’s actions were a part of a larger issue.

“Pugh’s sentencing is a reminder that this scandal isn’t an isolated incident, but a pattern of corrupt behavior across levels of city government,” she wrote. “I’m glad that she’s being held accountable for this behavior, but it doesn’t change the fact that government is often designed to maintain the status quo.”

Drukker-Schardl believes that the only reason Pugh got caught was because the scheme was so poorly organized that it was media and not law enforcement that first uncovered it.

However, Hardebeck noted that this kind of investigative journalism demonstrated how the press can hold government accountable. She applauded Luke Broadwater, the reporter at The Baltimore Sun who broke the story of Pugh’s scandal.

“One thing that gives me hope is the way local journalism in the city demands transparency from our leaders. We need to invest more here,“ she wrote.

Drukker-Schardl argued that ultimately it is the voters who must assume the responsibility for preventing corruption. In the upcoming mayoral elections in April, the voters must select candidates with established records of integrity and transparency, he wrote.

He also believes that systematic corruption within the city is what helps to validate much of the already existing public mistrust for Baltimore government.

“Corruption in our political system isn’t just about a foolish, hubristic mayor breaking laws in one of the strangest scandals ever. It’s also about city officials giving the wealthy and powerful... whatever they want, while ignoring the needs of everyday Baltimoreans,” Drukker-Schardl wrote.

Correction: The original version of this article identified Evan Drukker-Schardl as a Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development mayoral fellow. He no longer has this position.

The News-Letter regrets this error.