Philip Leaf, professor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, hosted members of Mothers of Murdered Sons and Daughters (MOMS), Family Survivor Network (FSN) and Tears of a Mother’s Cry (Mother’s Cry) on Tuesday.

The talk, “Being a Mother or Father of a Murdered Child,” was the latest presentation in his Lectures on Public Health and Wellbeing in Baltimore course.

Leaf was given the 2019 Crenson-Hertz Award for Community-Based Learning and Participatory Research.

In an email to The News-Letter, Leaf explained why he chose this lecture topic.

“I hope that the students will get a better understanding of the impact of the murders in Baltimore and the enormous strength of Baltimore’s mothers, fathers and youth who are living in Baltimore and what they are doing to break the cycle of violence,” Leaf wrote.

He aims to change his students’ perceptions of the victims of violence.

“Hopefully, after my class students will be more likely to ask ‘What happened to you?’ than to ask ‘What’s wrong with you?’“ Leaf wrote.

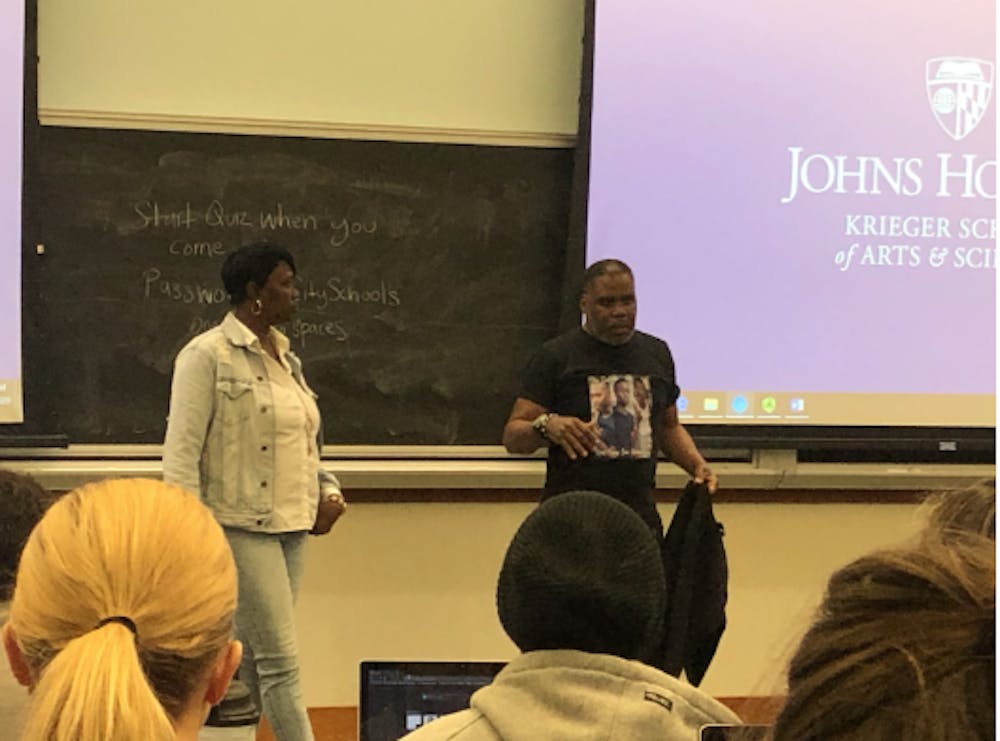

Wil Tyler and Tynette Robinson of the FSN were two of the first speakers.

Tyler wore a T-shirt with a photo of a young black man printed on it.

“This is my stepson,” he said. “I want you all to see this because this is real. I just lost him a month and a half ago. This is serious for us.”

Burnett McFadden of Mother’s Cry told her own story of dealing with death in the family. She has lost three of her sons.

“I was a mother,” McFadden said. “Now I’m the mother of a murdered child, that’s what I’m labeled as. It’s very hard.”

Pausing multiple times to compose herself, McFadden went on to describe being in the hospital and hearing the news of her sons’ deaths from the doctor.

“The scream came from the bottom of my soul. At that moment, I felt it was just me and God,” McFadden said. “It came from my belly. It came up through my chest...I felt every second of my children from the time they were born to the time my children died. What is happening to me? Am I losing my mind? Am I going crazy? No, this can’t be happening to me. And that scream came out. It’s called the scream of life. The scream of a mother or father losing their child. I screamed so hard and fell on the floor. I was lost. Not once. Not twice. Three times.”

McFadden went on to add that losing a child to murder is further complicated because the family of the victim has to attend court and face the murderer and their family while grieving.

She described being jealous of the family of the murderer.

“Their family’s got a whole lifetime to see them in jail,” McFadden said.

McFadden went on to explain that losing a child can also be extremely financially taxing on the family.

“I need you to see the receipt of the funeral cost. It ain’t a dollar. It ain’t two dollars. It ain’t three dollars. Who’s got thousands of dollars? Thousands of dollars that I had put out, while this murderer is running around free with his family,” McFadden said.

Tyler also spoke to the impact that losing a child can have on the family.

It creates psychological burdens that weigh just as heavily on people as physical ones, he argued.

“My mother lived in Sandtown for 80 years,” Tyler said. “She died in the past six months — it wasn’t her health; it was the deaths. This is serious. This is serious to me. This is not a game. This is not a joke.”

Many of the speakers talked about movements for the remembrance of victims that have begun in neighborhoods with high murder rates.

Robinson explained that she rallied her community around a wall on which they wrote the names of murder victims.

“I lost my son, DeVonte, on Jan. 19, 2019, when he was 26 years old. He had two kids,” Robinson said. “I’ve seen a lot of kids grow up with my son, and we say, ‘no more names,’ because most of their names are going up on the wall.”

Tyler spoke similarly of a legacy tree which the community planted for the victims. To Tyler, the tree is a deeply meaningful spot.

“That tree we built is a safe zone for me. I don’t need to go to the graveyard. I can sit and look at names. I can put my hands on their names and just remember who they are,” Tyler said. “My mother is up there. My wife is up there. My four sons are up there. My five nephews are up there.”

Many of the speakers talked about the importance of remembering the victims by their names, not just as their number of murder.

“My stepson, I don’t want to remember him as 189. I want to remember him as the name I gave him,” Tyler said.

Some of the participants in the lecture chose to touch on how issues of class and race intersect with the patterns of homicide in Baltimore.

McFadden noted how Baltimore’s black residents are particularly harmed by these patterns.

“This is genocide. It’s called black and brown people being killed,” McFadden said. “I’m a black mother. I’m tired. We’re tired. You think we want to lose our children? That we black mothers want to be up here speaking about our children?”

Mosiah Fit described how he drew inspiration from Marcus Garvey, a prominent early 20th-century black nationalist.

“[Garvey] saw that African Americans were... carrying a flag that promised life and liberty and the pursuit of happiness and all that bull crap, but they were getting lynched, hung and beaten, while holding this great red, white and blue flag,” Fit said.

Fit described the alternative flag that Garvey created using the colors red, black and green. For Garvey, red stood for the blood of African American ancestors, black for the black people and green for the wealth and prosperity of Africa.

Fit explained that his form of activism is creating human flags; specifically, using bodies to create Garveyite flags.

He claims that he does it to give people the feeling of being a part of something.

“So far I have done three flags,” Fit said. “My whole point with this is to raise awareness.”

Many of the other speakers talked about community work as well.

The executive director of FSN, Dorian Walker, likened working in the community to a job interview.

“When you’re doing community work, these are the people that you need to be saying hello to right when you step outside your door,” Walker said. “If these people are not sitting at the table when you are making decisions, if you haven’t sat down to talk with the people that you will be potentially serving, rework the way you are thinking. Listen to the people from the start and you’ll never have to rework what you’re doing.”

McFadden talked about how she served her community in the wake of her sons’ deaths.

“I am a freedom fighter. I fight. I go march. I speak in the House of Representatives to change the laws. I speak to Congress,” McFadden said.

Millie Brown founded Mother’s Cry while working in a hospital. She had just delivered the news of yet another child being murdered to their family. This time, though, she felt differently.

“This mother made a sound I had never heard before. It was a cry that shook my entire body. I held that mother in my arms and I knew, that day, that I had to do something,” she said.

Brown subsequently started Mother’s Cry, a support group for families which had been torn apart by murder.

“I couldn’t give them back their children,” Brown said. “I just wanted to give them a little bit of peace, a little bit of comfort. I wanted to try really hard to put a smile on their face.”