“Well, you know, you look... different.”

So said one of my friends during a casual dinner conversation one night. We noted that we were the only non-Asian people in the Japanese restaurant. The talk turned to race and how we ourselves identified. Both of us are Jewish, and both of us identified as white.

At least, that’s what I’d assumed when the conversation began. But as I tried to argue for my whiteness, my friend pushed back. Because of my Middle Eastern heritage, he said, I was not white. And if I did identify as white, I should know that I didn’t look the part.

I do know I look different. As someone who is a descendant of Iraqis, I don’t appear to be white on sight. But I’m also not sure that I can identify as a person of color, even though I feel that I should.

Growing up, I assumed that I was white. Race was simply never questioned. The Jewish school that I attended from kindergarten through 12th grade was predominantly made up of students who appeared to be white. None of my teachers implied that we were part of a minority race.

But as I got older, I began to notice differences among Jews. Some look white without question, while others look brown. Often, differences in appearance correlate with differences in one’s family’s geographical background.

Jewish people originally came from the area of ancient Israel. After being exiled, they slowly spread around the world. As they took root in other communities, they developed customs that related to the cultures surrounding them. Today, most Jews fall under one of three ethnic categories, defined by where their ancestors came from. Ashkenazic (meaning Germanic) Jews have a Central or Eastern European background. Sephardic (Spanish) Jews are Spanish and Portuguese. Mizrahi (Eastern) Jews are Middle Eastern and North African. Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews are often grouped together, as many of their prayers, foods and cultural traditions resemble each other.

My mother’s entire family comes from Eastern Europe, from the blurred line that existed between Poland and Russia in the early 1900s. My father’s parents, on the other hand, trace their history back through the Iraqi Jewish community for generations. According to tradition, they have lived in Iraq since the Jewish people were exiled from Israel to Babylon over 2,000 years ago.

My background, then, is 50 percent Ashkenazic Jewish, and 50 percent Mizrahi/Sephardic Jewish. Among Jewish people, I’m considered to be essentially mixed-race. My Mizrahi background implies that I’m not white, under the assumption that Middle Eastern people are not white. My Ashkenazic background is unanimously concluded to be white. As my mother explained, “Your grandparents weren’t Christian, but they’re as white as you can get.”

But when my other side comes into play, it’s my Iraqi appearance that is noticed first. I’ve been told that I look Israeli, Middle Eastern, Arab, Greek, Mediteranean, Hispanic and Native American (the last one is objectively false). Just weeks ago, while eating dinner with a Chabad Jewish family at another college campus, the wife asked me, “So, is your entire family Persian?” She was surprised to hear that none are, but nodded along upon finding out that yes, I am Middle Eastern.

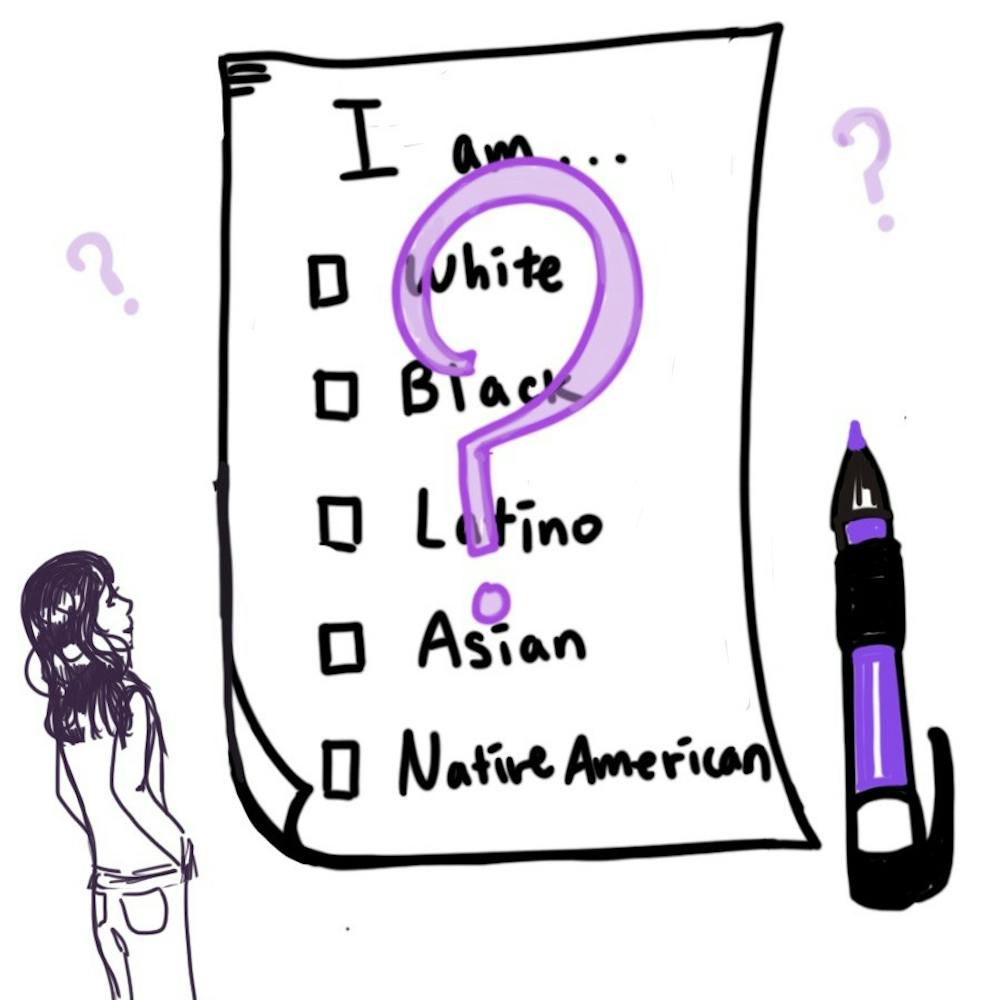

When it comes to checking off a box for race, I, like most Jewish people, feel compelled to mark off “white.” It most closely aligns with who I appear to be physically and my background. I may not be sure of my percentage of whiteness, but I know I’m not Asian or African American or a Pacific Islander.

In recent years, however, I’m gravitating toward the “other” option, in addition to marking off “white.” If there is an option for Middle Eastern, I check it off as well. Both of my parents’ backgrounds contribute to my race, do they not?

Eventually, I decided that the best answers will come from those who are like me — those who have a Mizrahi background, but don’t live in Middle Eastern communities anymore. The Facebook group “sounds ashkenormative but ok” exists for this purpose. It is an online community for Mizrahi and Sephardic Jews to rant and joke about being part of an “Ashkenormative” society, in which most popular Jewish culture ignores our customs and traditions.

I asked two questions in the group. Are Middle Eastern Jews white? And more broadly, are any Jews white? Several minutes later, I added a third question: If Jews are not white, what race are we?

I was overwhelmed with responses, but as I’d expected, I didn’t receive any clear-cut answers. “Too white for some, not white enough for others,” one commenter wrote. “All Jews are Middle Eastern, there’s no such thing as a white Jew,” began another response.

The best response, though, is one that I never considered before. One commenter wrote that Jews are an ethnicity, not a race.

Once the idea crossed my mind, I realized that it’s the best possible explanation: I can’t be defined on the basis of race. It doesn’t actually matter whether I am white-passing or not. It never did. The concept of race was not designed for me, for my unsureness and questioning of whether I fit in the right spot or not. The concept of race assumes that everyone fits neatly into their designated category, not that there is confusion behind the categories in the first place.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter whether I identify as white or not. As one response put it, “Know thyself... no one can put us in a box,” accompanied by a smiley face.

For now, though, I will continue being asked to check off boxes designating my race. And until I get a more permanent answer — in the form of an ethnicity question, or a definitive understanding of what race actually is — I will continue to answer the way I see fit. I am white, but I am also a Middle Eastern Jew, and that should not be ignored.