Sometimes the things I say sound like the babbling of a romantic idealist. My motivations for physics are too far removed from reality, my reasons for loving the subject too “soft,” and so I don’t know if I have ever really fit into the straight-back mold of an algorithmic physicist.

This is interesting to me: The idea of what a physicist should be like is somehow so ingrained in the pop culture and traditional narratives of our society. As a Muslim woman of faith, I don’t feel like I’m ever part of these narratives.

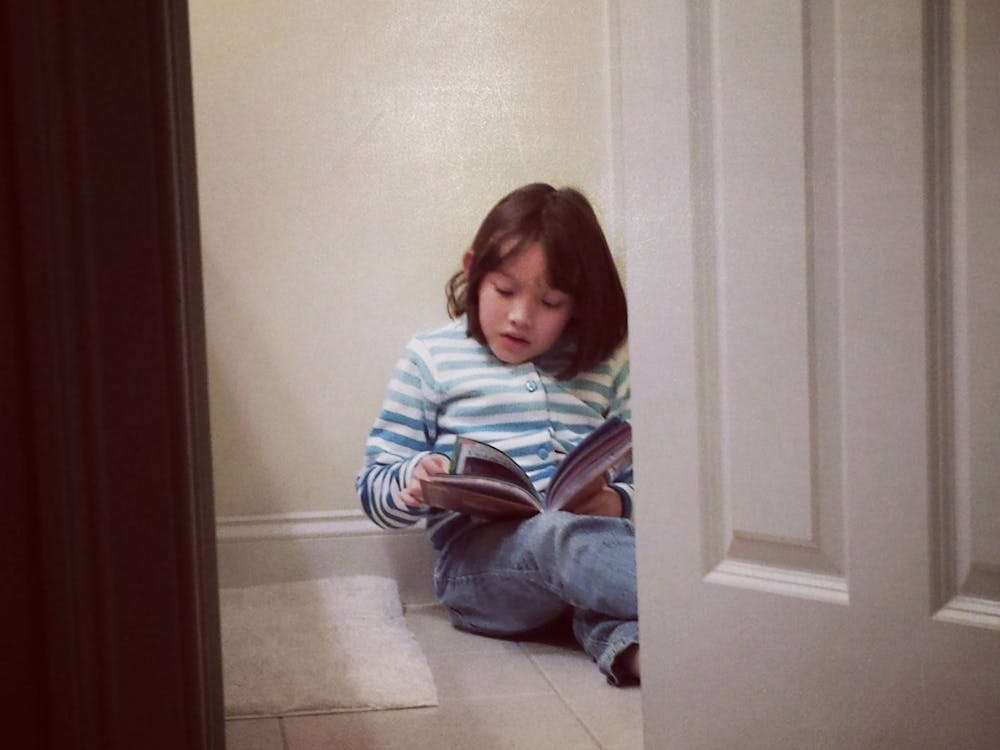

Physics and my relationship with God are perhaps the two most defining aspects of my identity. Physics is a relatively new one. Ever since I was young, I wanted to be a writer, but it wasn’t until the end of high school that I discovered physics was just another way of writing about the world. Since then I haven’t looked back. Through the confusing derivations, the exhausting problem sets, the technical jargon, I have loved physics because I love the way it describes the world. I love that it is trying to get to some truth — any degree of truth over how this world works, and that is beautiful to me. That is worth the torturous exams and the crippling self-doubt.

But God? Hmm. My relationship with God has been as long standing as my birth. As far back as I can remember, I have always had a relationship with God — not always a very good one, but one nonetheless. To me God was like this omniscient invisible friend who had all the power. So through the sluggish nights and the even more sluggish mornings, I would wake up and have some sort of conversation with this invisible being. Sometimes I would be angry about the way things had turned out, sometimes I would be grateful and sometimes I would be indifferent. Whatever my emotions, I made sure to convey them to this invisible being I believed in.

But here is where my dilemma lies. A girl who believes in a higher all-powerful being is not the cookie-cutter definition of a physicist who demands to see how things work the way they work. I don’t have an answer, I don’t know how God works, I don’t know how God exists, I don’t know why there is sadness in the world if there is a God who can make the sadness go away. I don’t have a reason for why I believe and I don’t have any logical justification for my faith other than it makes me feel better.

In my mind, physics and faith aren’t inherently irreconciliable. Being faithless does not automatically put you in the ranks of physicists, just like having faith does not mean you lack that certain skepticism that makes a physicist. But I have somehow always been told to some degree or another that they are inherently irreconcilable, two opposing sides and that I have to pick a side.

As far as I know, everyone in my physics department is tolerant and respectful of my faith. Then why would I never feel comfortable praying in Bloomberg? Maybe it’s because while the majority of people are respectful there have been a few incidents which remind me that this is not the most accepting place for faith.

For example, in my freshman year, while doing a group project with someone, I was told that there is a direct correlation between intelligence and belief in God. When I replied that there have been lots of Nobel Prize winners who have had faith, such as Abdus Salam (my personal hero), he proceeded to tell me that Salam would have probably been smarter and achieved more in his life if he didn’t believe in God.

Faulty and completely illogical reasoning aside, there is more to this. While I believe faith should never be used to explain science, there should be no problem deriving inspiration from faith. Salam, the man responsible for the electroweak unification theory, would say that the harmony in the laws of physics demonstrated the harmony in God’s creation. He was inspired by God to see the way the world worked through science. During his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he quoted from the Quran and connected it to what he sees in physics:

“‘Thou seest not, in the creation of the All-merciful any imperfection, Return thy gaze, seest thou any fissure? Then Return thy gaze, again and again. Thy gaze, Comes back to thee dazzled, aweary.’ This, in effect, is the faith of all physicists; the deeper we seek, the more is our wonder excited, the more is the dazzlement for our gaze.”

Honestly, that is physics for me. It’s wonder at the laws of this universe. It’s amazement, it’s dazzlement, it’s belief and disbelief that such a world exists. But mostly, it’s feeling grateful that I am lucky enough to be able to study such a world.

I don’t know if everything I have said right now is the antithesis of how a physicist thinks. I don’t know if I have completely missed the point of studying physics. I don’t know if I’m drawing connections that aren’t there. I don’t know if my romanticization of physics is going to lead me into big trouble one day. But for now I am happy sitting in my quantum mechanics class and being utterly confused about this wondrous, wondrous world.