Editor's Note: Drawing on the experiences of herself and her friends, Jin fictionalized the names and certain events in parts I and II of this column.

I) Although Sasha looked upset, I grasped her hand in mine and pulled her up to stand. Herr Neumann gestured for our orchestra of odd instruments to take a bow. Lights flooded the church hall as families stood to congratulate their children. As an exchange student, I didn’t expect my own, but I still smiled and scanned the audience for familiar faces. I turned to congratulate Sasha on her solo in our adaptation of Schubert, only to be met with unfocused eyes to the floor, her lips downturned.

It was June, and June 15 signaled that I had only 15 days left in Germany; Sasha had arrived in March, and for her, she didn’t know when her time would end. After the concert, we went to Basak’s for dinner, the Turkish restaurant across the street from our school. I didn’t plan on experiencing Turkish culture while in Germany, but with an open mind, I tried it, and now Basak’s döner yufka remains an all-time favorite.

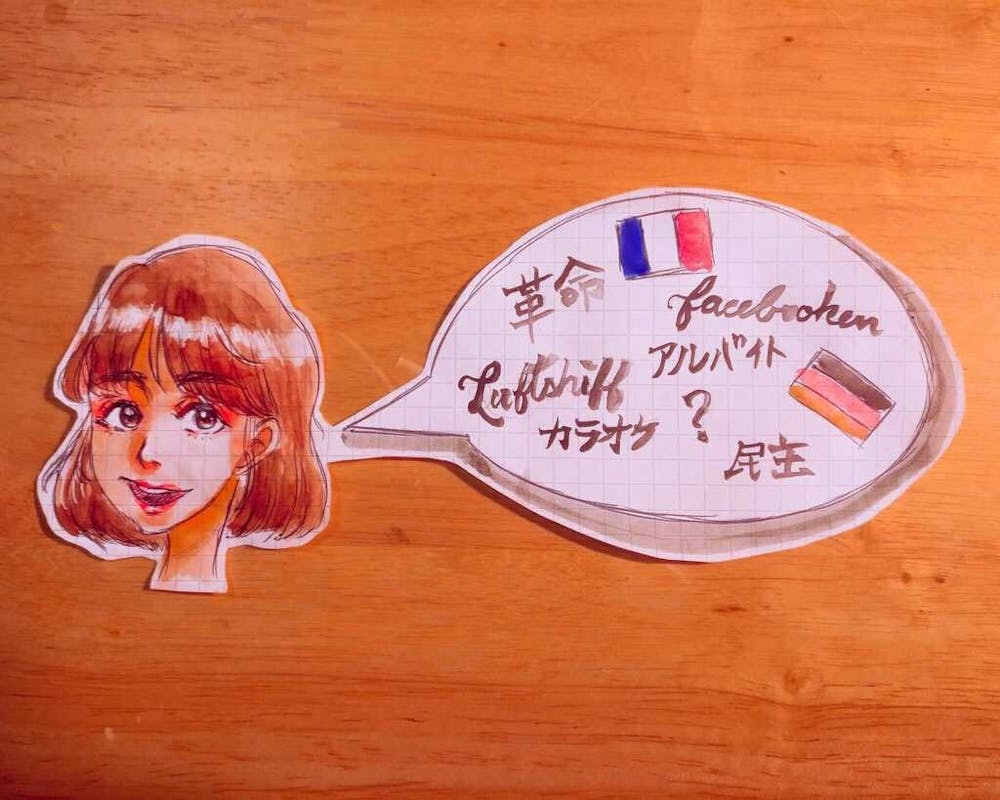

I heard from across the room, “Okay, I haven’t gefacebookt him in years....” As a gaggle of young girls entered the shop, their words blurring into the air, I thought back to a documentary on Texas German I’d seen. For German diasporas in Texas, there came a time when modernity outpaced the 19th-century vocabulary of the community. Anglicisms began replacing standardized German: Luft-schiff (air-ship) instead of the German Flugzeug (airplane), or ge-jump-t instead of German sprang (jumped).

Ironically, I thought, listening to the girls now, standard German too has adopted its own Anglicisms. Facebooken (to Facebook), for example, or even just “okay.” These were words brought into the German language 30 years ago, after the wall came down.

II) Three days passed. On our way home from school, Sasha approached me. “My father died. He couldn’t leave Syria.”

Together we went to the government building, collecting pamphlets to be passed out to the neighborhood where Sasha lived. On our way, we picked up ice cream for Daniel, Sasha’s younger brother, who’d left his Arabic at the quarantine center as he stuffed German in his mouth.

The Refugee Orchestra came about after Sasha and I played a duet for a local music competition. Before leaving Germany, I returned to our music room, where we’d spent months communicating without words, crafting a world within our Eastern and Western instruments.

The room was dark, the orchestra now empty.

III) Three years passed, and I’d gone to Japan. Sitting in Starbucks, overlooking Shibuya Crossing, I revisited this language game.

Following the 1868 Meiji Restoration, Japan experienced a period of rapid industrialization. As Japan opened itself to the Western world, Japanese scholars realized that new words needed to be created to describe newly imported ideas. Words from different languages were co-opted: German arbeit (work) became arubeito; French concours (competition) became konkuru. Later, using foreign words as a base, they created their own word combinations — icecandy means popsicle, with karaoke derived from the Japanese kara (empty) and oke (orchestra).

IV) Though culture is seen as that which defines a people, it’s ultimately the people themselves who create it. The creation of new words such as “democracy” and “revolution” in the Japanese lexicon allowed for the dramatic social advances at the turn of the 19th century. These linguistic adaptations continued to remain grounded in their native grammar and culture: “adapting” certainly differs from “forgetting.” But the language of a time serves only to parallel the zeitgeist of then; its malleability reflects the exchange of cultures, changing times and the progress of humanity.

Just as the Japanese adopted from other cultures to further self progress, I look now to societies around the world for good ideas, and adopt them into solutions suitable to my own contexts. The ways in which other countries address broader issues — such as healthcare, sustainability and education, to name a few — compels me to put a mirror to American policies and see how we may improve our nation.

The issues of today, such as the refugee crisis, may certainly point towards more complex questions than answers. But these problems cannot be tackled by any individual alone. It’s only through the collective work of intellectual discourse, shared and debated across boundaries of country and society, that we can discover the best solutions to the problems of today.