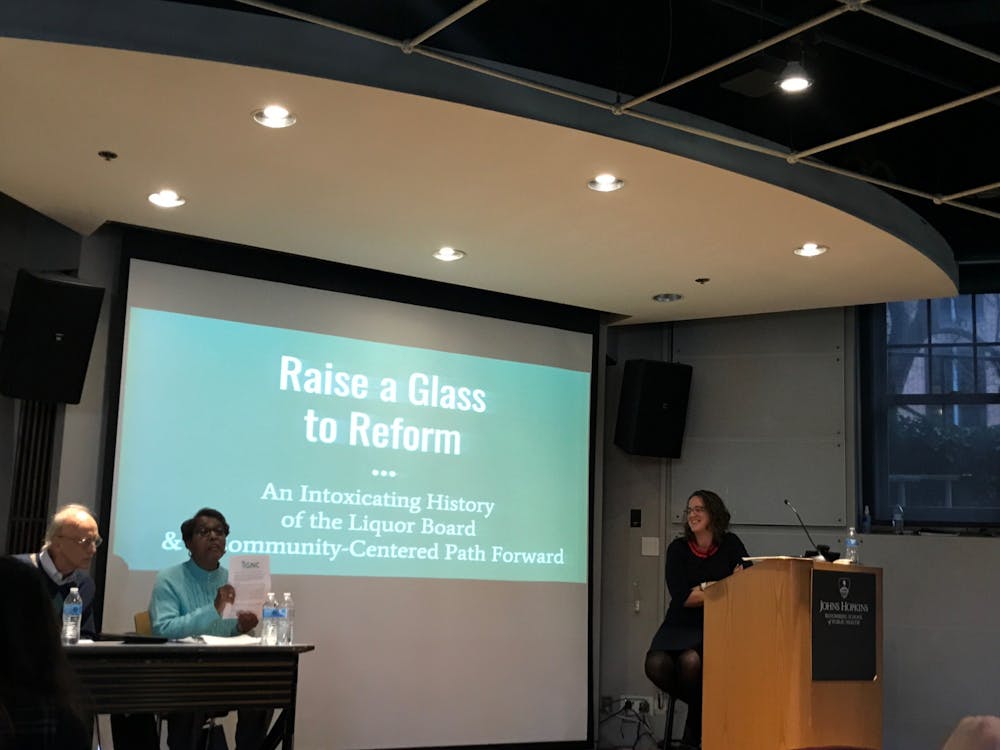

Community Law Center Staff Attorney Becky Witt led a discussion on the Baltimore City Liquor Board’s current and historical approach to alcohol regulation enforcement on Friday at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The Baltimore City Liquor Board is a state agency that regulates retail sales of alcohol to customers within alcohol outlets located in Baltimore City.

Panelists included Inez Robb, a Western District Police Community Relations Council member; Janice Bowie, the director of Bloomberg’s Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) program; and Lowell Larsson, a Greater Greenmount Community Association member.

To preface the discussion, Witt recounted her excitement when she first began representing nonprofit organizations and neighborhood associations in Baltimore City Liquor Board hearings.

However, Witt explained that she quickly realized that fighting for liquor board reform would be extremely difficult.

“There are very real, historical and structural issues for why the agency has been unfriendly to communities. The system isn’t broken, it was built this way,” Witt said.

Robb echoed Witt’s sentiments, commenting on her own experience with the liquor board.

“After every hearing, I have left unheard, disappointed, disrespected. [Each hearing] was a waste of time, energy and money. Something’s wrong, there’s got to be a better way,” she said.

Witt attributed the Baltimore city liquor board’s failure in properly regulating alcohol sales, especially in disadvantaged communities, to three reasons: the liquor board’s lack of public health-oriented goals and missions, its tendency to dismiss input from disadvantaged communities and its historical roots as a political patronage system.

She emphasized that the current Baltimore liquor board mission statement simply states that they will regulate alcohol beverage establishments, but fails to outline any public health goals that extend beyond the immediate scope of alcohol regulation.

“You could imagine a liquor board mission statement that says something about eliminating disparities, that might say something about reducing the amount of harm from alcohol consumption in Baltimore City.” she said. “None of that is present and never has been from anything that I’ve seen from the liquor board. It’s just that ‘we’ regulate alcohol. But for what? Why are we doing this?”

Witt explained that in 1940, civil rights leader and president of the Baltimore NAACP Lily Jackson wrote a letter to The Baltimore Sun, in which she highlighted the prevalent concern in black communities about the high number of alcohol outlets in their communities compared to white communities. Witt stated that in response to Jackson, The Baltimore Sun editorial board published a letter that strongly insinuated that it was the responsibility of black neighborhoods to monitor their own neighborhoods and ensure that the alcoholic beverage law was enforced.

Witt underscored that the liquor board continues to redirect the blame for lack of alcohol regulation in these disadvantaged communities onto the residents themselves.

She cited a study done in Baltimore which found that every additional alcohol outlet leads to a 2.2 percent increase in violent crimes in a particular neighborhood, and that alcohol outlets — especially liquor stores — are highly concentrated in black neighborhoods.

Witt highlighted the issues with the liquor board’s current complaint-based system in which the liquor board inspectors only conduct investigations in neighborhoods where they receive complaints.

She stated that for this reason, the communities that use the complaint-based system tend to be communities that already have political power and trust the system, a similarity to when the board operated through political patronage.

Witt argued that liquor board inspectors must shift their focus to disadvantaged neighborhoods where complaints may go unreported but are still problematic.

“It’s really important to use a race equity lens to concentrate resources where they are most needed. Right now, resources are being concentrated... based on complaints, which are not necessarily where those resources are needed,” she said. “They are... the places that people know how to use 311 and are willing to call their city councilmen a bunch of times.”

Witt noted that hiring new staff with previous public health training and experiences could serve as a crucial strategy to improve the efficacy of the liquor board.

However, Bowie cautioned the audience not to make the assumption that those with specific educational backgrounds will automatically be champions for reform.

“I would want to be careful about who these [new staff] are, what it is [that] they value and the contribution that they’re going to bring,” she said.

Bowie emphasized the importance of moving away from the dominant conservative societal narrative — in which large-scale issues are blamed on the individuals that partake in these risky behaviors — and instead focusing on the systemic upstream factors that push these individuals to partake in these risky behaviors in the first place.

“It’s important to be mindful about the persistent, intractable inequities that have long-standing histories, and how these inequities, and these social drivers and structures facilitate and continue to foster the disparities,” she said.

Robb addressed her own frustrations with the multitude of alcohol outlets in her own community in Sandtown-Winchester.

“Where I live in Sandtown-Winchester, there’s a [high] concentration of liquor stores, almost one [liquor store] on every other corner, if not every corner,“ Robb said. “People waiting for the bus, children going to school, they’re frightened. In some places, [liquor stores] are selling to underage kids. When we go down to the board, we say, ‘We’re tired of this; it’s just dirty, trashy and dark.’“

Correction: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the Baltimore City Liquor Board (BCLB) is located within the Baltimore City Comptroller’s Office. The BCLB is in fact an independent state agency and is governed by the State Alcoholic Beverages Article.

The News-Letter regrets this error.