A few weeks ago, The News-Letter published the op-ed “Focusing solely on electability will not get Democrats elected.” The article presents a well-written, cogent argument against the prioritization of “electability” in the Democratic primary race. It followed an earlier piece on the necessity of a moderate Democratic nominee in 2020.

The logic goes something like this: Democrats should resist the temptation to choose a candidate purely because of his or her perceived ability to defeat President Donald Trump next year, because doing so would play to Republican narratives and stunt enthusiasm for the eventual nominee.

The piece argued that when determining “electability,” Democratic voters focus on a candidate’s identities, ideology (generally, are they “moderate” or “radical”) and status in public opinion polls against the president. The argument posits that the perception of electability feeds on its own momentum. This kind of thinking, then, gives us a candidate whose utility plummets after Election Day. Electoral victory becomes the end goal of the candidacy, and leaves the presidency itself as a mere afterthought.

I don’t necessarily disagree with this formulation, but the punchline of the piece — that Democratic voters should not focus on electability — is deeply flawed. Essentially, it misunderstands what has actually enabled candidates to get elected in recent races: not identity, ideology or polling data but individual agency and charisma. In the race to defeat Trump, electability is still the single most important feature a candidate can claim — but we need to redefine the term in order to properly assess who might be electable.

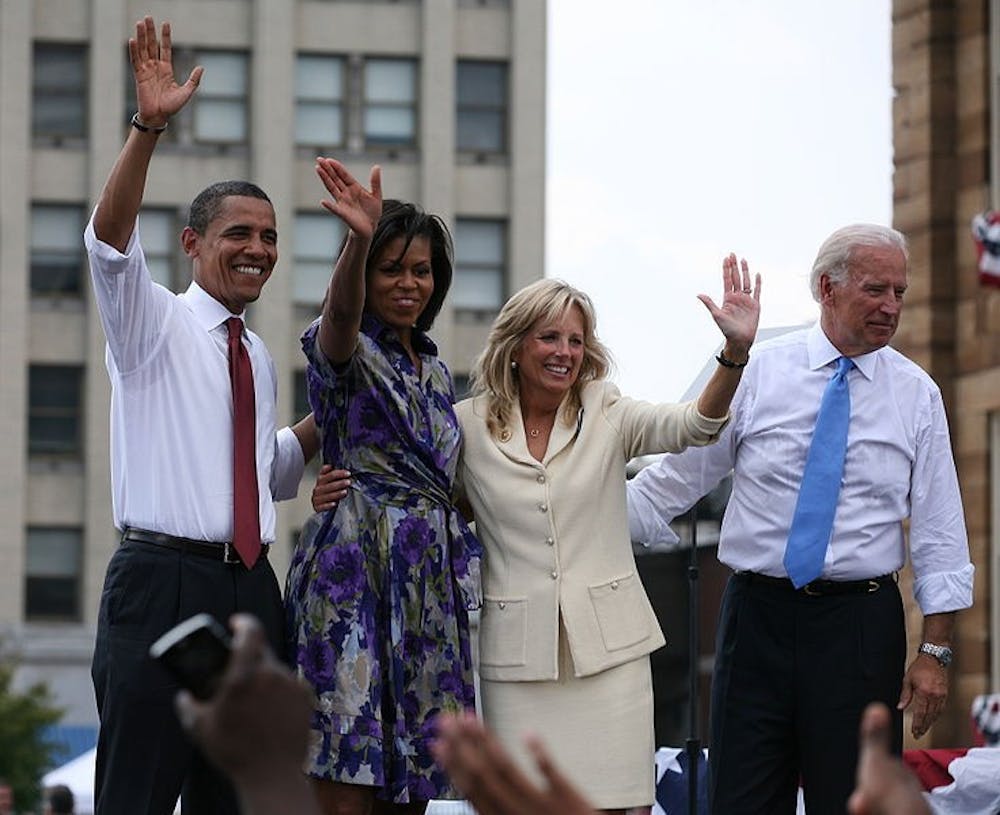

Barack Obama and Donald Trump were not initially seen as electable candidates. Obama was young and relatively inexperienced. He was the first person of color ever to be nominated for the presidency by a major party. Trump was an audacious, brash candidate who lacked any political experience at all. Still, they both managed to flip the meaning of the term “electability” on its head.

We can no longer think of the terms “electable,” “uncontroversial” and “traditional” as synonyms. Instead, electable candidates are those who can mobilize political support by crafting a clear driving message and delivering it with passion and clarity.

Electable candidates are charismatic and bold. They speak directly to voters, and they refuse to allow their political opponents to dictate the terms on which they speak. The American electorate has proven in recent elections that non-traditional candidates are fully capable of defeating archetypal politicians if they are especially effective in delivering their message to the public.

Those messages, of course, extend beyond the policies that candidates talk about on the debate stage. Obama’s message was one of hope and optimism: He depicted himself first and foremost (if somewhat vaguely) as a candidate the country could believe in. From this underlying message flowed his policy proposals like health-care reform and a stimulus package to end the Great Recession.

Like that of his predecessor, Trump’s campaign started not with policy proposals, but with a driving philosophy (in this case, a promise to restore a lost status of American “greatness”). Without worrying about the specific policies that would follow from this starting point, the then-candidate communicated his vision for national restoration to a public that was more than willing to listen.

The Obama and Trump electoral victories prove that to be “electable” no longer means being uncontroversial or traditional.

Without this new understanding, Joe Biden would seem to be one of the most electable candidates in the Democratic field. He fits the physical description of a traditional politician (white, male, um... not young), he is polling well and his policies are ostensibly centrist. To Democrats fearful of a second Trump term, Biden looks like the safest bet.

But that’s exactly why he is not the safest bet. Without an obvious driving message, Biden’s candidacy seems to be defined by little more than his connection with President Obama. As much as many of us would like to see a third Obama term, Biden needs to mark his own path. So far, he has failed to take ownership of a driving idea that voters can rally around.

If we think of “electable” candidates as those who are able to concisely convey their motivating philosophies, as leaders who refuse to compromise on their ideals but who instead convince the electorate that those ideals are worth fighting for, then it becomes clear that electability remains exactly what Democratic voters should be thinking about in 2020.

Really, we don’t need a moratorium on the word “electability” — we need a reformulation of the term. Democrats are justified in their obsession with electability. Where they seem to be going wrong is in just what, exactly, that word will mean in 2020.

Tim Shade is a junior from Baltimore, Maryland studying Political Science and International Studies.