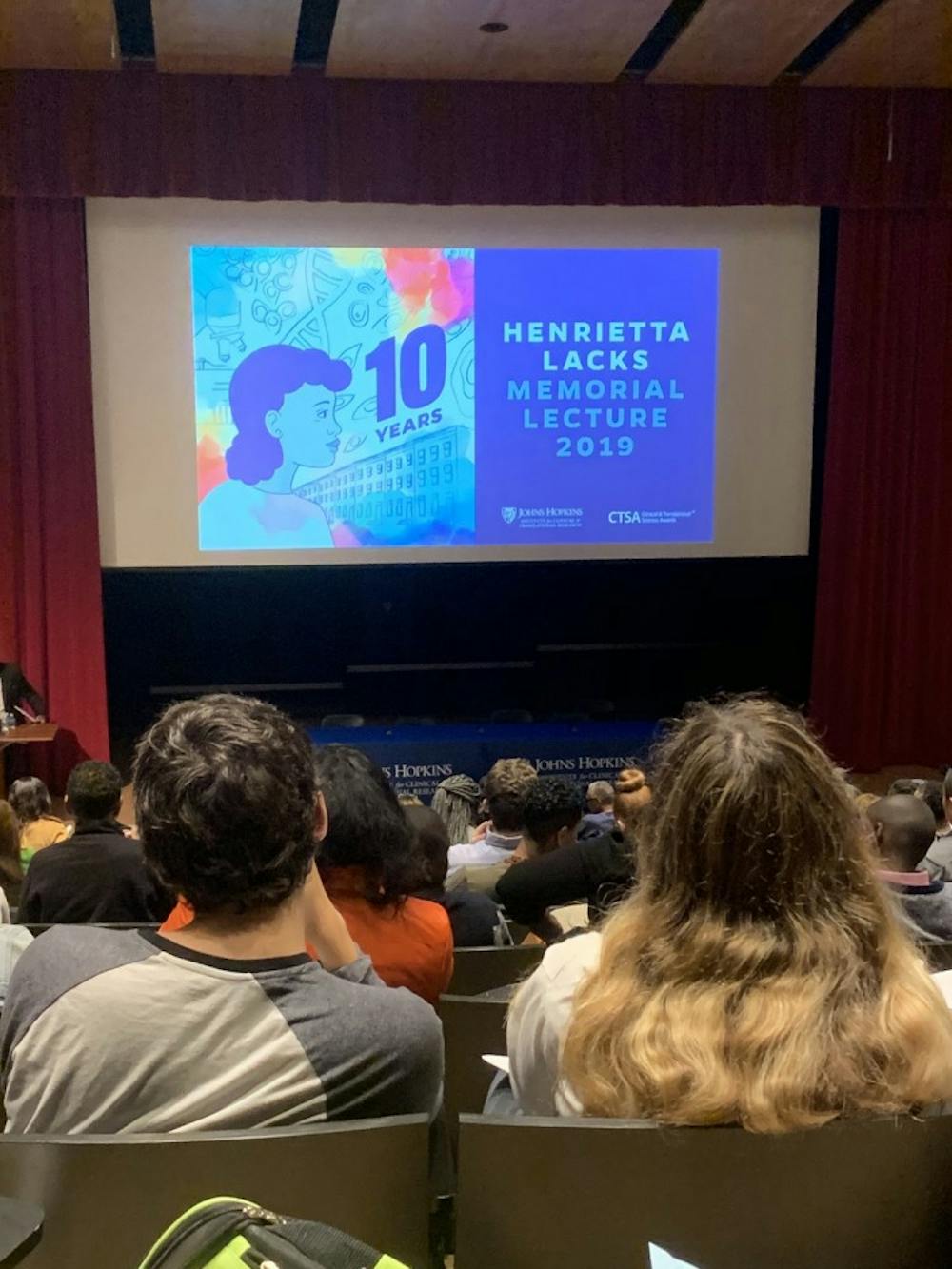

On Oct. 5, the Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) held its 10th annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture Series at the Turner Auditorium at the Hopkins East Baltimore campus.

Henrietta Lacks was an African American woman who underwent treatment for an aggressive form of cervical cancer at the Hopkins Hospital in 1951. During her stay, doctors removed some of her cancerous cells without her consent. Henrietta Lacks ultimately succumbed to her cancer at the age of 31. However, her cells, known as HeLa cells, are immortal.

They perpetually continue to reproduce to this day, 68 years since her death. Before this cellular biology breakthrough, cultured cells had only survived for a few days. Her cells have been instrumental in many of the most significant medical health discoveries of the late 20th century, and continue to play an important role in medical advances worldwide.

This year, four of Henrietta Lacks’ descendants participated in the lecture: her two grandsons David Lacks Jr. and Alfred Carter Jr, and two of her great-granddaughters, Aiyana Rodgers and Veronica Robinson.

The lecture began with a talk by Dr. Roland Pattillo, professor emeritus of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Morehouse College, on “Historical Reflections of the Henrietta Lacks Story.” Pattillo detailed the many ways in which HeLa cells have made a significant contribution to medicine, including their use in the research of three Nobel Prize Winners.

“The HeLa cell has revealed the inner workings of the human cell to a greater extent than any approach we’ve ever used… accounting for 4000-5000 publications a year. In that way, we continue to learn from her legacy,” Pattillo said.

Dr. Terri Powell, associate director of the Hopkins Urban Health Institute (UHI), presented the Henrietta Lacks Memorial Award to MERIT Health Leadership Academy, an education nonprofit that is transforming high school students into health care leaders.

Dr. Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, gave a speech entitled “Ethics, Gene Editing and Cell Lines — Looking Ahead” which explored the explosion of gene-editing technologies and the ethical issues they raise. He also discussed how cell lines like HeLa will continue to play a role at the leading edge of science and medicine.

Dr. Griffin Rodgers, director of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, gave the keynote speech, “The Economic and Social Imperatives of Disease Prevention: The Obesity-Diabetes-Kidney Disease Paradigm.” Rodgers discussed the connection between diabetes and kidney diseases in relation to the shocking rise in obesity in the U.S., and several clinical trials exploring treatments to address this health-care problem.

Following Rodgers’ speech, audience members were able to submit questions for a Q&A moderated by Ford. Many of the questions addressed ethical concerns of African American patients like Henrietta Lacks, whose contributions to research studies went unnoticed for half a century. Among the five panelists was Robinson, executive director of the Lacks family’s nonprofit organization Henrietta Lacks HeLa Legacy Foundation. She discussed the larger implications of this issue.

“This comes down to a question of how we bridge the gap between the community and the health-care field,” Robinson said.

She went on to advocate for increased participation in clinical research.

“Research relies on the participation of everyone… to solve problems in health care. My great-grandmoth er is an example of that,” Robinson said. The audience unanimously agreed.