In the United States, 50 percent of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnoses throughout the country occur in just 48 counties and seven states. Baltimore City is one of these disproportionately affected areas.

The Center for AIDS Research Investigators Symposium, held at the Bloomberg School of Public Health on Monday, focused on this specific issue. The symposium featured two speakers who primarily work on the treatment of HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) in Baltimore City.

Dr. Joyce Jones, an assistant professor of medicine at the Hopkins School of Medicine, addressed the need to maximize Baltimore’s treatment of HIV in her talk titled “The Baltimore Rapid Start Coalition: Creating Hubs for Rapid HIV Treatment and Prevention in Baltimore City”.

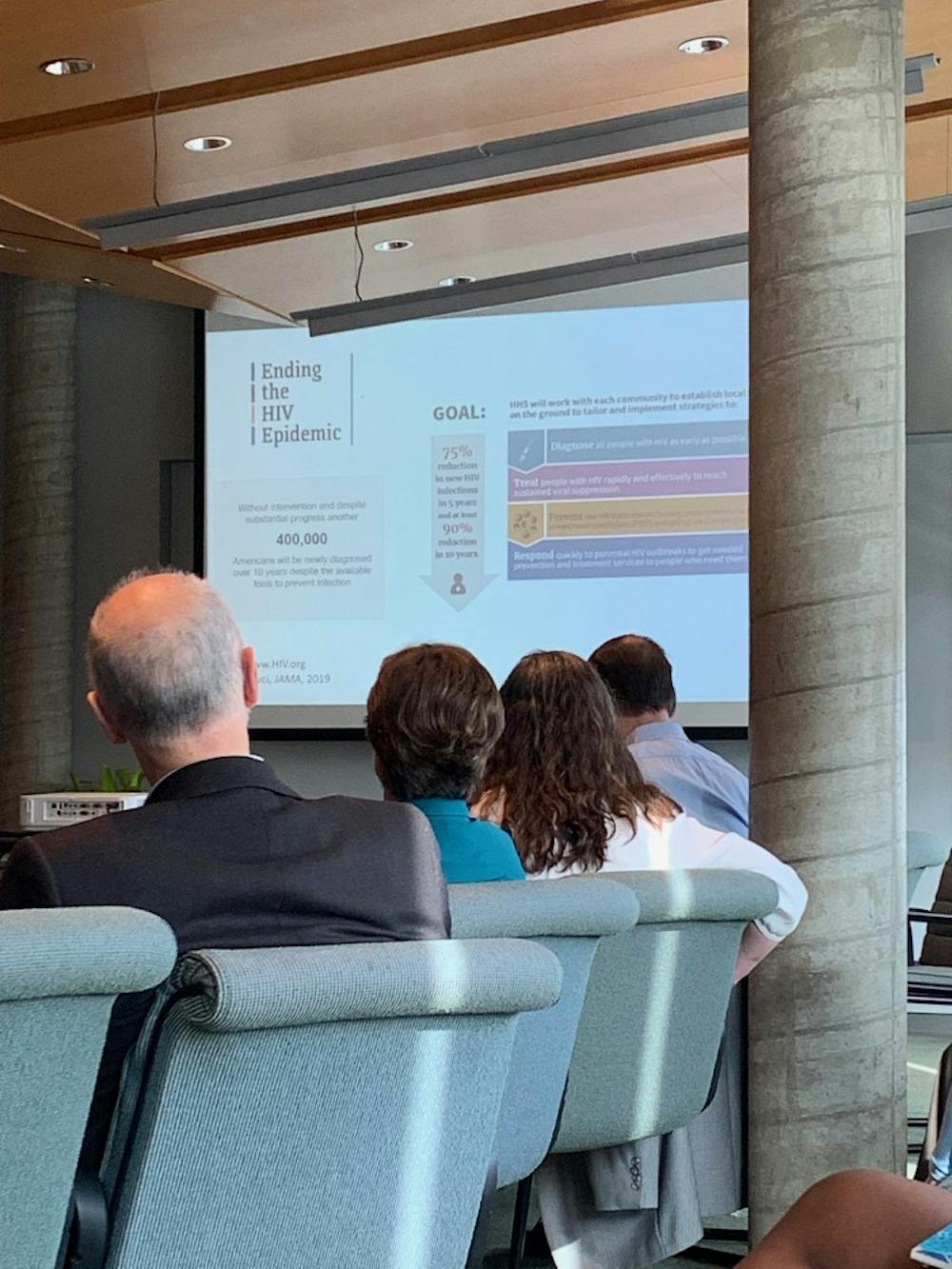

Jones’ presentation began with a fact she hopes to change: Without intervention, another 400,000 Americans will receive a new HIV diagnosis this year. Such information has led to increased attention on the management of the HIV epidemic in areas representing a substantial burden of HIV. As a result the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that its main goal regarding the HIV epidemic is a 75-percent reduction in new HIV infections in five years, and at least 90-percent reduction in 10 years.

After introducing these facts to the audience, Jones emphasized the importance of taking advantage of the opportunities present in Baltimore, and the country as a whole, to control the HIV epidemic.

“We are a wealthy country that has the means by which to end the HIV epidemic. We should gather our resources to really address the problem here,” Jones said during the presentation.

Aiming to aid the achievement of the HHS’ goal of reducing new HIV infections, Jones began to study rapid HIV treatment initiation in Baltimore.

Rapid HIV treatment initiation refers to the process of immediately starting patients on medication after they have received a positive HIV diagnosis. When patients start HIV medications sooner, the virus is more easily controlled, and the patient achieves viral suppression at a much quicker rate. Viral suppression means that the HIV virus will be undetectable in a patient’s blood. This does not mean that the virus is gone from the body but that the patient cannot transmit the virus to their sexual partners.

Two trials served as inspiration behind Jones’ investigation into the feasibility of implementing a rapid-start program in Baltimore. A randomized trial in South Africa demonstrated that rapid treatment initiation led to decreased time before HIV treatment was received, which decreased the amount of time needed for a patient to achieve a suppressed viral load. In addition, a study in San Francisco showed a great deal of promise, with patients receiving medications sooner leading to positive outcomes.

Upon receiving funding from the Center for AIDS Research, Jones and her team were able to facilitate and study clinical services related to rapid start at the John G. Bartlett Specialty Practice at Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore City sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics and inpatient services.

Jones’ talk outlined the main objectives of her study of rapid HIV treatment initiation in Baltimore: develop the best practices for rapid start and rapid prep in the city; implement these practices and create clinical hubs; evaluate outcomes; and partner with the city, state and health-care providers to create a system that addresses the patient’s needs and easily facilitates care.

Her study found that an overwhelming majority of HIV patients wanted rapid start if it was available and offered to them.

More specifically, the study showed that 95 percent of patients who were offered rapid start wanted to pursue treatment. After identifying the demand for rapid start among HIV patients who were offered this service, Jones and her team worked on implementing rapid start in the Baltimore area. Patients were started on medication when they came to any of the participating clinics and were linked to a care program with the Johns Hopkins Emergency Department and state health department STI clinics.

Despite the existence of multiple studies throughout the U.S., including Jones’, that highlight the demand for and benefits of rapid start, Americans have not fully embraced rapid start.

According to Jones, barriers to rapid start are usually related to our complex health-care system. When HIV patients are seen in clinics, many factors must be navigated by health-care providers before they can receive the care they need. These factors include patients being uninsured, under-insured or having an insurance that restricts getting services at certain places — the patient may need a referral or prior authorization before they receive care.

Jones commented on several patient barriers in an interview with The News-Letter.

“The [Center for Disease Control] recommends opt-out testing; all adults that haven’t been tested should get tested when they visit a health-care center,” Jones said. “Stigma related to HIV is also an issue. Some patients don’t recognize they’re at risk — when you are in an area with a high prevalence of HIV (more people who do not have viral supression) the risk of infection increases beyond one’s individual sex practices.”

Jones closed her presentation by expressing optimism about the future of HIV treatment, despite the complexities that physicians, clinicians, health-care providers and most importantly patients face.

“We have the tools to end the HIV epidemic,” she said in her presentation. “What we’ll need to do is reconfigure some of our current clinical practices and increase our collaboration among clinical providers, communities and the health departments.”

Dr. Risha Irvin, assistant professor of medicine at the Hopkins School of Medicine, followed Jones’ talk with her own: “Alcohol Use, HIV, HCV, and the Continuum of Care.” Irvin’s talk centered around the barriers to HIV and HCV treatment briefly mentioned by Jones. More specifically, Irvin addressed the importance of removing restrictions on access to HCV medications based on patient alcohol abuse.

Both providers and insurance companies deny patients access to Hepatitis C medication based on documented alcohol use in medical records. These providers and insurance companies cite reduced treatment adherence among individuals with alcohol and substance abuse as the reason behind their restriction of treatment.

Irvin and her team were interested in the relationship between alcohol abuse and failure to initiate HCV treatment or cure the patient. They used two tools to study alcohol abuse among patients with HCV. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) identifies alcohol consumption and drinking behaviors, and creates a composite score that classifies a patient’s alcohol use based on their answers to three interview questions. Her team also used phosphatidylethanol (PEth) testing, which detects an alcohol-specific biomarker in red blood cells that indicates heavy alcohol consumption. Consumption is typically detectable for about two to three weeks with PEth.

The study’s findings showed no substantial correlation between alcohol abuse and failure to initiate HCV treatment. According to Irvin, neither AUDIT nor PEth results were associated significantly with failure to initiate treatment in the individuals studied.

Irvin’s research supports the HCV Guidance Panel recommendations which prioritize treatment for all persons, including those with active alcohol use disorders. Irvin made it clear that providers and insurance programs should grant HCV patients access to the vital treatment they need, despite their alcohol use. Physicians and relevant health care providers can then work on connecting the patient to a more long-term intervention that can help them with their alcohol or substance abuse.

One common theme stood out in both talks: the need for health-care providers, clinicians, physicians and the general community to be more understanding of individuals who have been diagnosed with HIV. Although there have been incredible advances in the treatment of HIV — advances that can truly make HIV a rare occurrence — Jones acknowledged that there is still a long way to go.

“I think the reason we’re not at a point where we’re reaching people who can benefit from these treatments and prevention is because of all of our societal baggage,” Jones said in an interview with The News-Letter. “Moving forward, yes, we need to do more research into a cure and vaccines, but at the same time we need to do more work to help make sure that the people who can benefit from these very powerful treatments receive them. This is going to require work that addresses issues such as social justice, racism, trauma, homophobia, society’s view of those struggling with injection drug use, transgender individuals, people who have multiple partners and those engaged in commercial sex work.”